For years, when the subject comes up, I have claimed to own 500 cookbooks. In fact, until a couple of weeks ago I had no idea how many I owned, though I could probably count – on one hand – and recite by name – those I have given away, reluctantly given away. (And those that have walked away. “Rick Bayless Everyday Mexican” with that tortas recipe I want to try, where have you gone?)

But this spring, unpacking and re-shelving my cookbooks for the fourth time in just 10 years, I decided to count them, and I came up with 334 cookbooks, more or less, plus another 160 books about food. In the latter category, such items as memoirs by Betty Fussell, histories of the spice trade and the no-nonsense “The Maple Sugar Book” by Helen and Scott Nearing. That last entered my household long before I lived in Maine, and I’m tickled that it has found its way home.

Add 334 cookbooks and 160 general food books together, as I just did, and you get 494, so it turns out my guess was eerily accurate. Because the books tend to be scattered around my apartment, they are difficult to count. There is a constant yet ever-changing stack next to my bed, which I read before I go to sleep, my version of counting sheep. There is a stack in the room with the TV. After long days at work, I unwind by watching strangers rehab and flip houses – as I flip through cookbooks.

There is a shifting stack on the kitchen table with the recipes I intend to cook next marked with odd bits of torn paper and sticky notes. At the time I am writing this sentence, those happen to be Pistachio and Cardamom Pound Cake with Lemon Icing (“American Masala,” 2007), Triple Caramel Cake (“The Best American Recipes 2005-2006”) and “Lamb Meatballs in Warm Yogurt Sauce with Sizzling Red Pepper Butter (“Yogurt: Sweet and Savory Recipes for Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner,” 2015).

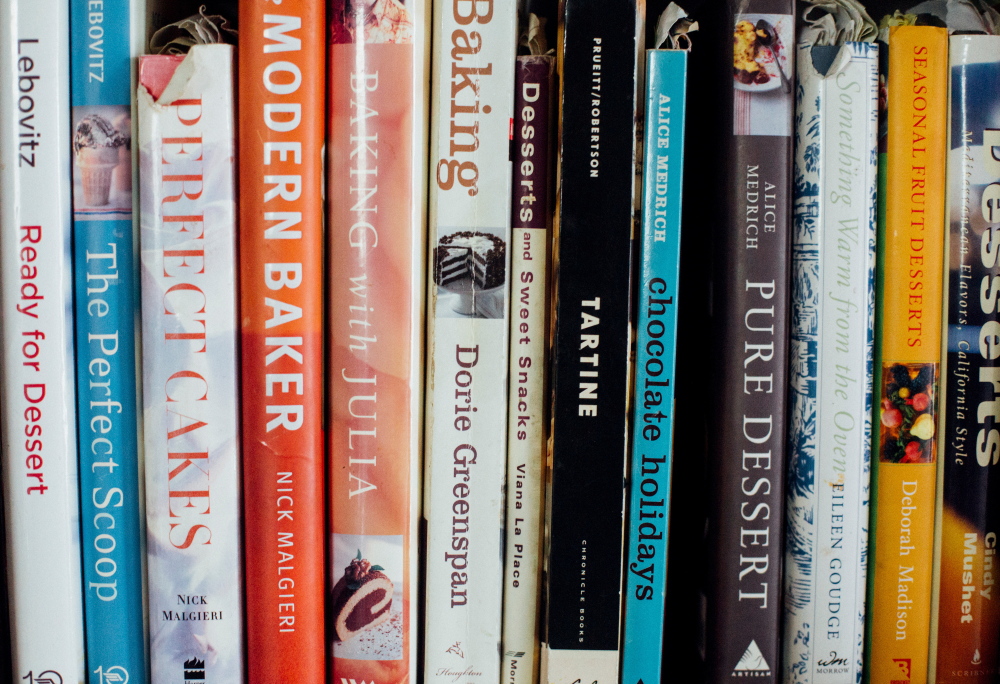

Can you tell that I love to bake? Do you wonder how many baking books I own? On this page, one sentence flows into the next, at least I hope so, but in fact, I paused just now and went over to my bookshelf to count: 77, more or less.

What I wonder is why I own so many cookbooks at all. The easy answer is because I write about food for a living. Twenty years ago, I could have said, I would have said, that I needed the books for recipes and reference. But now, both are as near as my smartphone, the recipes in quantities I could never hope to cook even if I locked myself in my kitchen until I died. Is it the reverse? I write about food for a living because I own so many books? The books reveal my interests, that is, and I’m lucky enough to have work that interests me.

The day I moved to Portland, a cold, clear day in February, a third-floor apartment, I tipped the movers generously and bought them a “Meatza,” a pizza clogged with pepperoni, sausage, bacon and hamburger. After they’d lugged their last box, they handed me the bill, their faces gleaming with sweat despite the cold. “You’re a nice lady, but don’t call us the next time you move,” they said. “You have too many books.”

So this time as I re-shelved, I set out a large empty box with the intention of filling it with discards. I tried using the principle I’ve been told to apply to my closet: if you haven’t worn it in a year, get rid of it. If I haven’t looked at a book in a year, out it goes. So far, though, just nine books have taken up residence in that box; a few more moved in for a spell but have since migrated back to the shelves. Meanwhile, the box itself has faded into the landscape of my living room. My cat likes to rub her head on it, and what if it turns out I need that cheese book after all or I finally manage to convince myself that I care about the science of cooking so Harold McGee’s “On Food and Cooking” should stay?

McGee was a guilt purchase. I’ve been surprised to discover that I have fewer of those than I expected – books I think I am supposed to own if I want to be taken seriously in the food field, and maybe one of these days I’ll actually get interested in them. Also in this category – and I should not admit this publicly – is Julia Child’s “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.” Some years ago, I told my mother that I wasn’t interested in the family silver because “I just don’t live a silver lifestyle, Mom.” Most nights, I barely manage to pull spaghetti together for dinner. If Child were to materialize in my dining room, I’d make a similar argument: “I just don’t live a Sauce Mousseline Sabayon or Cervelles Au Beurre Noir lifestyle, Julia.” I’ve come round to the silver, though. Perhaps I’ll come round to Julia, too.

The truth is I own dozens of cookbooks I never cook from. Only part of my collection, such as it is (no real collector would ever count me in their ranks), is about getting in the kitchen. My cookbook library is not about value, either, at least not monetary value. I described my ragtag collection to Don Lindgren, owner of Rabelais Fine Cookbooks in Biddeford: mostly books from the 1970s on, I told him, a few older ones, many smudged, many missing covers, many damaged corners and bent pages, my scribbled recipe notes throughout (“a bit of a pain but quite delicious,” “brought cookies to Fla. Everglades w/ Carolyn. They held up,” etc.).

Are my books worth anything, I asked? “Well,” Lindgren said, hesitating politely. “Not really… There are a lot of used books in the world.” (That’s the short version. In fact, he generously spent 20 minutes on the phone and spoke articulately and fascinatingly about the nature of collecting, shelf order, physical objects versus electronic ones and his own collections.)

So why do I own them? Why do I lug them from here to there? And why do I keep acquiring them, breaking the strict cookbook diet I put myself on a decade ago?

The cool kids in high school – I wasn’t one, not even close – could talk about their record collections in excruciating detail, linking certain songs or albums with exquisite precision to certain people or events in their life. My cookbooks do the same for me.

In the pages of “Cooking with Lydie Marshall” (1982), for instance, I run into myself at age 20 in my first-ever job as a reporter; it was at a small weekly in Greenwich Village. I was passionately interested in food at a time when not so many people were, so I gave myself the greatly elevated title of Cookbook Editor. When Marshall’s cookbook was published, I scheduled an interview; she was then a well-known French cooking school teacher in the Village. I was very young. She was very kind. She wrote in the flyleaf: “To Peggy, who had an earful of my talking about the school and myself. Please keep me in the kitchen.” As I thumb through the book this morning, I pull out a sticky note and mark “Upside-Down Prune and Apple Tart.” I’ll make it next fall when apples return.

That same year, 1982, I got a cookbook from my then boyfriend’s parents with whom I spent Christmas. It’s a facsimile of “Hershey’s 1934 Cookbook” and the inscription reads “For sweet memories.” I adored the gift givers, more than the boy himself, my mother once ventured, although he was the first boy I ever loved. Mr. W is dead, and I haven’t seen Mrs. W in more than 30 years. But they live on in my memory and on my shelves.

The Hershey’s book sits next to “Betty Crocker’s Cook Book for Boys and Girls.” Published in 1957, it’s older than I am. I can say with total certainty that I will never make the Whuffins (Wheaties cereal folded into Bisquick mix muffins) nor the Raggedy Ann Salad (“Body – fresh or canned peach half; Arms and legs – small celery sticks; Hair – grated yellow cheese,” etc.). But the spiral-bound book charms me, so it abides with me.

“Larousse Best Desserts Ever” (1982), a recent score at a Goodwill store, carries what may be my favorite inscription, this one in big, generous letters that are sprawled across the inside cover: “Happy Valentine’s Day – 1983. I love you – May we grow old and fat together! Love, Bob.” Who was Bob? Who was she? The book is pristine. Didn’t she ever bake him a cake? Did they grow old and fat together? (And will my own beloved cookbooks one day be set adrift?)

I could spin out similar paragraphs for almost every cookbook I own. I’ll spare you. Here’s the CliffsNotes version: I have cookbooks written by friends and by the mothers of friends. Cookbooks written in foreign languages (Danish, French, German). Maybe someday I’ll learn those languages, I’ve lied to myself, so that someday I can bake that torte (about as likely as my again fitting into that teeny-tiny once favorite dress that still hangs in my closet). There are cookbooks from old boyfriends (with corresponding notes: “Matt loves this cake”) and the cookbook my mother gave me when I went off to college – “The Joy of Cooking,” what else? I have cookbooks from my first and last restaurant jobs (The Frog Commissary Cookbook, 1985 and Flour, 2010). There’s a section devoted to Texas, where I spent several happy years cooking, eating and writing. And a smattering of wine books that remind me of my repeated vows, and repeated failures, to get to know wine deeper and better.

“If you are looking purely for a really good succotash recipe, sure you can get on the Internet and find 1,000 succotash recipes,” Lindgren said. “When you have a cookbook that you’ve owned for some time and cooked out of for some time, you have a relationship with that book and with the author of that book; you have some knowledge of their point of view. The sum total of that book, the picture of the author, the things you’ve cooked out of it, the foreword, the writing and what was going on in your life when you bought that book are all part of the thingness of that book. It’s the personal history that clings to that object.”

The thingness of the book. That resonates.

Years ago, I watched my friend Mitchell Davis offload several hundred cookbooks without a second thought. How did you do that? I emailed last week to ask him. Apparently, he’s recently done it all over again. “Funny,” he wrote back. “When I moved into our new apartment (more than a year ago). I gave them basically all away. I don’t know. Catharsis.”

I’m not there yet, and I’m guessing I never will be. My cookbooks are faithful companions. They let me time travel. Through them, I visit vanished decades, past selves, old friends (including Mitchell, whose four cookbooks I own. We catch up, at least it feels that way, whenever I make his Curried Carrot Spread).

In the last 25 years, I’ve moved more than 15 times, a process that never gets any less disorienting, forced all over again to find new grocery stores, new dentists, new places for lunch, new habits, new friends. But not new cookbooks.

Send questions/comments to the editors.