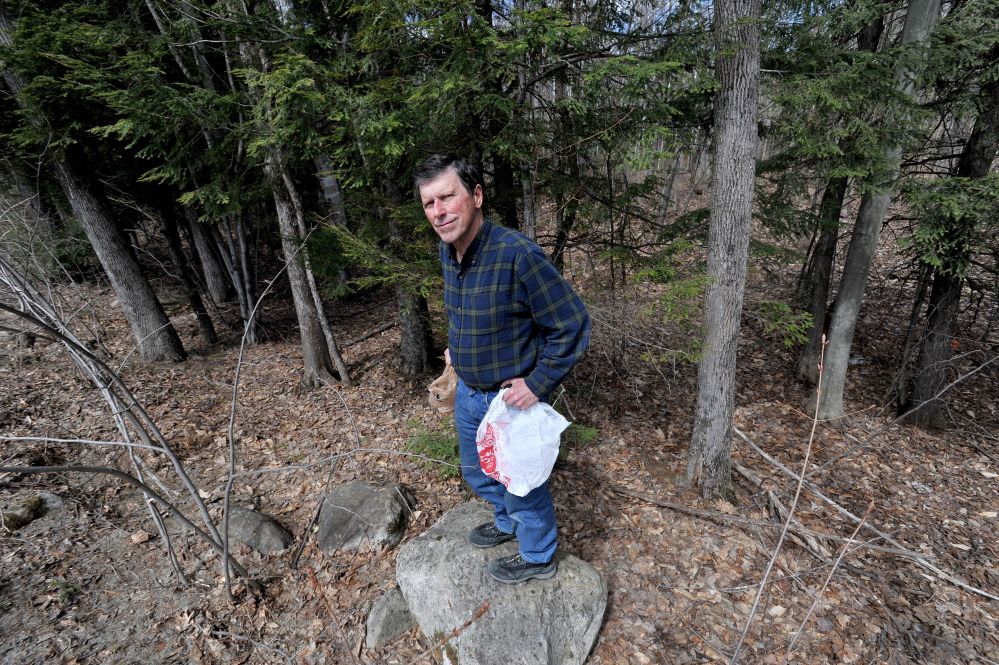

When Game Warden Tom McKenny found piles of trash on private property on Martin Stream Road in Fairfield last week, he wasn’t surprised. He’d been dealing with the same issue on the land for two years.

The old logging roads on the property are strewn with trash bags and large items such as old couches, televisions, toilets and mattresses.

McKenny isn’t sure why people would dump their trash on the property rather than going to the town transfer station.

“It’s kind of pathetic,” McKenny said. “I think it’s just laziness.”

The Fairfield site is a notorious one for the Maine Warden Service, which usually gets calls about dumping sites, but there are thousands like it around the state. Often hidden down logging roads, in the woods or otherwise out of the public eye, dumping sites aren’t visible to many, but their impact is huge, not only on the environment, but on the state’s traditionally generous public access land use.

Getting more attention than most dumping issues recently was the case of two dozen buckets filled with soiled adult diapers dumped along streams in Farmington and Wilton. That case was called unusual by the Maine Warden Service because it was on public land and the nature of what was dumped. But illegal dumping itself is anything but unusual in Maine – it’s a quality-of-life issue often cited by landowners whose land is defiled.

With 94 percent of its land private, Maine has a nearly four-century tradition of allowing public use. But landowners, in an influential 2008 survey by the University of Maine’s Jessica Leahy, said the biggest reason to cut off that use is littering and illegal dumping.

Nearly 40 percent of the landowners surveyed reported that the public does things on their land that they don’t want, with littering as the top problem and illegal dumping right behind. About 30 percent of private landowners were “actively considering” placing restrictions or prohibiting access in the future to their property, primarily because of problems with littering and illegal dumping, according to the research.

The pervasive and difficult-to-solve problem tends to frustrate law enforcement, landowners and recreation users alike, said Leahy, an associate professor in the School of Forest Resources at the University of Maine who specializes in land use issues.

“Much of illegal dumping is not from recreation users,” she said. “It’s from local people who are not using their transfer station.”

With most of the residents of central and northern Maine dependent on town transfer stations rather than municipal garbage pickup, Leahy said dumping often happens because people don’t want to pay to dispose of garbage, the transfer station hours don’t fit their schedule or because they have items that are difficult to dispose of, such as tires, appliances or building materials.

Cpl. John MacDonald, spokesman for the Maine Warden Service, said posting land against use is up to a landowner.

“A lot of large landowners choose not to post their land,” he said. “They don’t need to (leave it open), but they choose to because they want to let people recreate.”

Generally, game wardens deal with illegal dumping issues with private landowners and are trying to maintain a relationship that lets the land stay open for public use, said MacDonald. But wardens see the same things Leahy’s study found.

“If you have somebody dumping garbage on your land, you have a tendency to want to shut the land down,” he said.

DUMPING GROUNDS

When Mario Carrier bought a large tract of land off Martin Stream Road in Fairfield two years ago, his goal was to let the young trees on the property grow so his brother could harvest them through his logging company.

The property – on a remote section of dirt road near the Norridgewock town line – isn’t posted, which means it’s open for public use.

Last fall, Carrier got a letter from a hunter asking if he could go on the property. He agreed. Shortly thereafter, the hunter sent him another letter, this time with photos of trash that had been dumped in the woods on the 450-acre tract.

Not long after that, a game warden called and said there was more dumping and they were looking for the people who had done it.

“There’s no doubt it bothers me,” Carrier said.

He hasn’t posted the land against public use, but does plan to put up signs warning against dumping.

By not posting his land, Carrier part of a tradition that dates back to Maine’s Great Ponds Act of 1641 that allows anyone to cross private land for recreational purposes, and has promoted a recreation culture of open land access in Maine.

Landowners can post their land if they want hunters or people in general to stay off it, but many don’t.

In Mount Vernon, George Smith, the former executive director of the Sportsman’s Alliance of Maine, finally posted his land after years of finding garbage on it.

Smith said until he posted his land three years ago to ban public use of his property, he was constantly finding garbage strewn about his land.

“One time my fire pit was full of Bud Light cans,” he said. “It was just infuriating.”

Smith said if someone knocks on his door and asks him if they can use his land, he generally says yes. But he still continually cleans up garbage on his road and in the area.

“I’m out there every day,” he said. “I can’t keep up with it.”

While litter is a daily bother – Smith said Bud Light, Marlboro cigarettes and chocolate milk seem to be favorites of litterers – he also frequently finds appliances, air conditioners and tires on his land.

‘THEY JUST DON’T CARE’

Anger over illegal dumping took center stage in Farmington and Wilton last month when five-gallon buckets full of used adult diapers were found dumped along Martin Stream.

The Maine Warden Service asked twice in April for the public’s help in catching whoever is responsible for dumping at least 24 buckets full of dirty diapers in streams and along riverbanks in the two Franklin County towns.

Hundreds of posters have made irate comments on online articles and social media posts about the diaper dumping, voicing disgust over the idea of polluting a river and decrying the dumping as “environmental sabotage.” Some have bemoaned that Mainers “have far too few places left that haven’t been spoiled by thoughtless people” and that the dumper was “ruining everything we as wildlife enthusiasts are trying to achieve.”

MacDonald, of the warden service, said the case of bucket dumping in two streams is being investigated by Warden Kris McCabe. The warden service’s request for the public’s help has led to some good tips, he said.

MacDonald said illegal dumping is a problem statewide.

Rachel Ohm can be contacted at 612-2368 or at:

rohm@centralmaine.com

Twitter: rachel_ohm

Send questions/comments to the editors.