BERLIN — When Paul Schmitz was a little boy, he never understood why kids in his tiny German village taunted him as a “Yank” and beat him up. He was a teenager by the time he found out: His father was an American soldier his mother had a romance with as World War II ended.

Schmitz was born about five months after Victory in Europe Day, when the Allied forces defeated Nazi Germany 70 years ago Friday. It would be the start of a life as an outsider, burdened by fear, discrimination and loneliness. He is one of at least 250,000 children of German mothers who got pregnant by Allied soldiers as the Third Reich crumbled.

Now many of those children have embarked on quests to find their fathers.

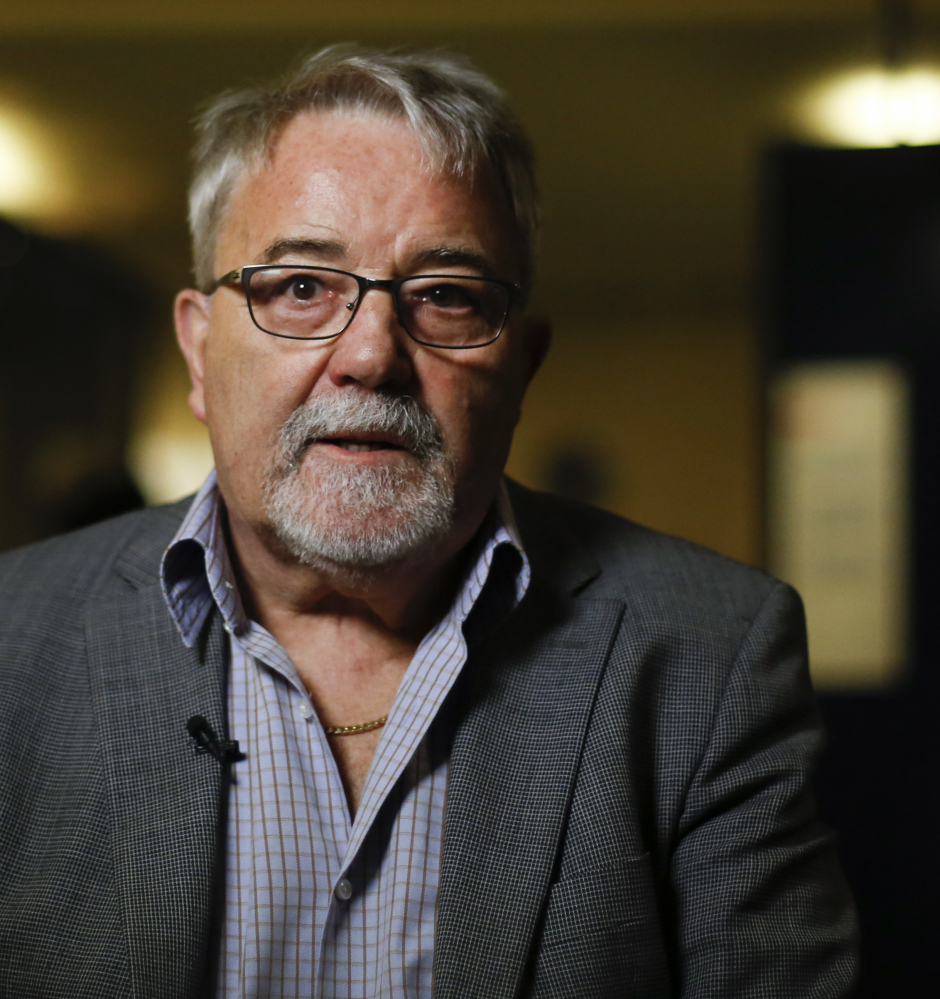

“I was a child of shame, a child of the enemy, even though it was the Americans who liberated us,” says Schmitz, a shy 69-year-old with a friendly round face. “All my life I had a yearning for my father, but until recently I was too afraid to actively search for him.”

WHO IS MY FATHER?

Schmitz decided to start looking for his dad 10 years ago, among hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Germans who have launched searches for their Allied soldier fathers in recent years. The search is often painful, but can also bring closure and answer nagging questions about identity and heritage. As the generation of children born at the end of the war has reached retirement age, and their kids grown up, they have organized self-help groups and used Internet research tools to solve the mystery of their unknown fathers.

“Almost all war children start their search alone, spending nights in front of the computer,” said Ute Baur-Timmerbrink, who found out in her 50s that she was the daughter of an American officer. She is part of the group GI Trace that helps other war children look for their dads – quests that succeed about half of the time.

Many of the aging war children feel they have one last chance to discover the truth.

“After seven decades, these people are at a stage of their lives where they ask these questions: Who am I, where do I come from, what are my roots?” said Silke Satjukow, a historian who wrote a book about the war children. “Of course, they know that their fathers will most likely be dead by now, but they’re still hoping to find ‘shadow families,’ siblings who were born after their fathers left Germany.”

Schmitz talks haltingly about his difficult life as a fatherless boy in post-war Germany. His eyes well up recalling the hardships he faced.

LAST TO KNOW

It took him years to figure out that he was just about the only one who didn’t know he was a “war baby.” When he was around 14, he asked his mother why he didn’t have a father; she tersely revealed the truth. A few years later, she told him that his father’s name was John.

Most kids in Schmitz’s situation felt unwanted: The mothers were ashamed and the U.S. military forces did not want to have anything to do with them, saying it was a private matter. The fathers themselves often started new families back home without imagining they might have a child in Europe.

For Schmitz, it was only after his mother had died, and his own children had grown up, that he found the courage to look for his American father.

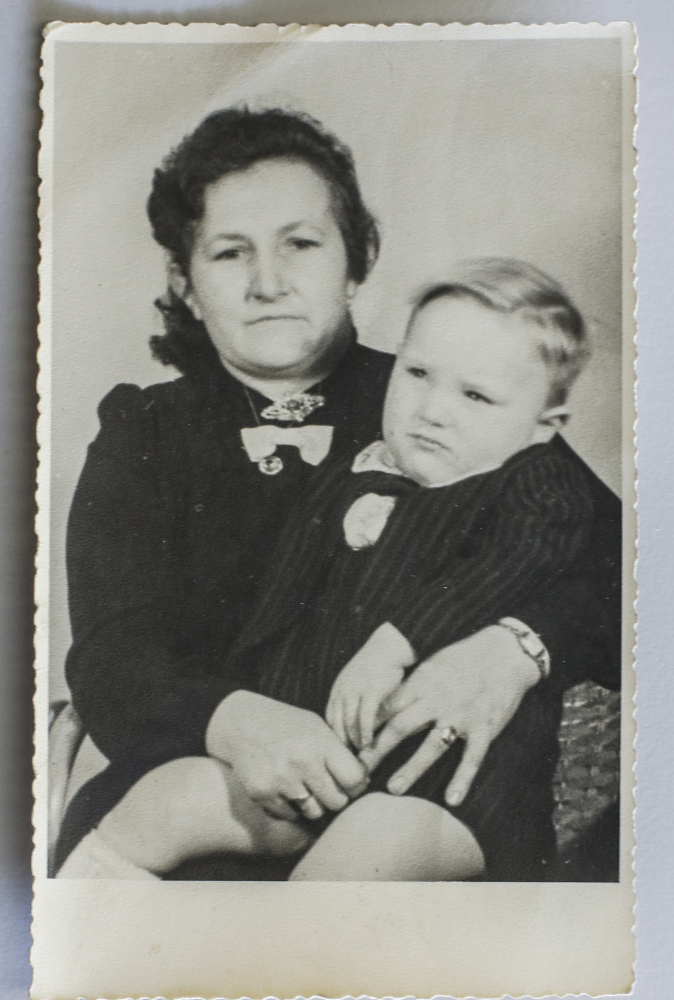

The quest took him to a Belgian village just across the German border from his village, where his mother Margaretha Schmitz, then 32, was evacuated by the Americans during the Battle of the Bulge.

Schmitz found an old lady who remembered that his mother was friendly with a soldier named John, part of a medical battalion. With the help of veterans groups and archives in the United States, Schmitz finally found out that his father was John Kitzmiller, a physician from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Kitzmiller was no longer alive. But Schmitz tracked down two half-sisters – and met them during a trip to the U.S. in 2011.

They took him out on family picnics, shared old pictures, showed him his father’s grave. Before parting, they handed him his father’s old wrist watch.

Send questions/comments to the editors.