High ozone levels remain a problem in York County even as conditions have improved in other parts of Maine, a report released Wednesday by the American Lung Association says.

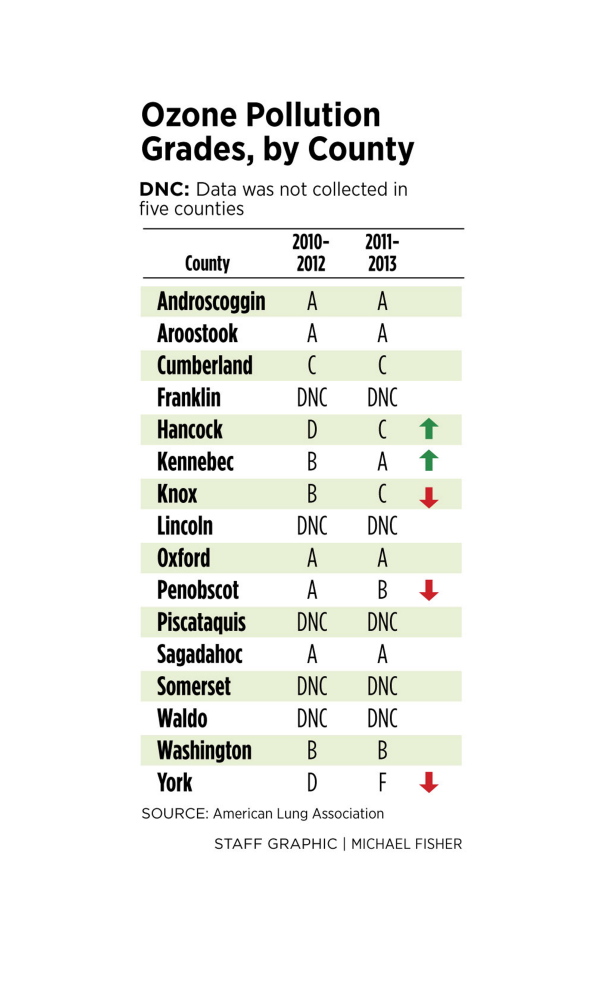

The annual report, which assigns a letter grade to each county based on a rolling three-year average, found ozone pollution had improved in Hancock and Kennebec counties; deteriorated in Knox, Penobscot and York; and stayed the same in Androscoggin, Aroostook, Cumberland, Oxford, Sagadahoc and Washington.

York is the only county to receive a failing grade in the report, which is based on data from 2011 to 2013. It received an F, down from a D last year. All other counties received an A, B or C.

The five other counties – Franklin, Somerset, Piscataquis, Lincoln and Waldo – do not have appropriate monitoring stations and are not included in the report.

The report comes nine months after federal officials approved a controversial request by the LePage administration to opt out of certain anti-smog regulations under the Clean Air Act, a move supported by the paper industry. Critics of Maine’s request – including the Maine Medical Association, the American Lung Association, conservation groups, and the states of New York and Delaware – argued that parts of Maine were barely in compliance with existing ozone standards and would likely fall out of compliance when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issues new, tighter standards later this year.

“We’re not doing that great and we’re on the edge, so this is not the time to be looking for waivers,” said Edward Miller, vice president of public policy for the American Lung Association of the Northeast. “Instead, we should be pushing for a stronger standard and for out-of-state polluters to be in compliance as well, since that’s where a lot of our ozone-causing pollution is coming from.”

Miller emphasized that the new report is based on data up to the end of 2013, so the changes are not due to the weakened ozone rules, which were not approved until July 2014.

Ozone is a health concern because it can irritate lungs when inhaled and can trigger asthma attacks. The Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 10 percent of Mainers have asthma, one of the highest rates in the United States, where the figure is 7.8 percent.

OZONE RULES CHANGE

The rule change proposal came about in late 2012, after a company that was considering creating a wood pellet facility in Woodland expressed concerns about the cost of offsets it would have to buy in order to emit volatile organic compounds – or VOCs – a type of pollution that contributes to smog. The Maine Department of Environmental Protection made loosening the rules for VOCs and another smog-causing family of pollutants, nitrogen oxides, a top propriety for the department, public records showed.

In 2013, the DEP asked the EPA to allow it to exempt major new, or newly upgraded, industrial polluters across Maine from certain rules. The rules required the companies to either buy offsets or install the best available pollution control technologies if their projects would otherwise increase significantly the emission of either of the two categories of pollutants. Paper industry representatives strongly supported the changes, saying they would remove a barrier to major investments in Maine paper mills, including conversions and upgrades that will actually improve air quality.

The request was controversial among other Northeastern states that are members of a smog-fighting compact, the Ozone Transport Region, in which Maine and 11 other states had agreed to adhere to the same standards to improve air quality for everyone. Experts agree Maine’s air quality has been improving because of reduced pollution from other states carried here by the prevailing winds. New York and Delaware officials argued the pact would be weakened if Maine were allowed to break ranks.

On July 29, the EPA approved Maine’s request to eliminate the requirement that industrial companies buy offsets for any additional nitrogen oxides created by new plants or major refits. It rejected the loosening of similar rules governing VOCs.

“Maine is meeting current federal standards for ground-level ozone and is not contributing to ozone in other states,” the EPA said in a statement explaining the approval. It said that if new ozone standards are promulgated – which most observers expect to happen later this year – Maine would have to reapply for the waivers.

“It was very shortsighted for the state to have done this in light of the fact the standards were going to change,” said John Chandler, a 40-year veteran of the DEP’s air monitoring department who now sits on the board of the lung association’s Maine chapter. He says the least expensive way to meet tightened standards is by using the best technologies when a major investment in an industrial facility is made.

“They should have waited to see what the new standards will be, because if we do fall into non-attainment, there will be some very expensive things we would have to do,” he said.

Marc Cone, director of the DEP’s bureau for air quality, disagreed, saying he’s confident Maine won’t be in violation of even a tightened federal standard. “We’ve continued to see a decline in the ozone levels in the state,” he said, noting the summer of 2014 was the first to have no ozone alerts since monitoring began in the 1970s. “We continue to see more pollution controls to the south of us and that’s bringing us cleaner air.”

Cone also took issue with the lung association findings for York County, noting it based its grade on data from just one of three monitoring stations in the county. If data from the other two – located in interior Hollis and Shapleigh, instead of coastal Kennebunkport – had been considered, the overall pollution level would have been lower.

The lung association responded that in choosing monitoring data on ozone problems, it follows the same approach the EPA does: For a given day, it selects the monitoring site with the worst readings, and in the case of York County, the Kennebunkport site was always the worst.

The expected beneficiaries of the changes are the state’s remaining paper mills. Dixon Pike, the Pierce Atwood attorney who represents the Maine Pulp and Paper Association, said recent upgrades at the mills in Baileyville and Lincoln would not have triggered any requirements under the old nitrogen oxide rules, but that future investments in kilns, dryers or power plants at Maine mills may benefit from the change.

The new lung association report also found that Maine continues to see improvements in particulate pollution – essentially soot from tailpipes and smokestacks, with every monitored county receiving an “A” grade.

Correction: This story was updated at 2:29 p.m., April 29, 2015, to give the correct job title for Ed Miller. He is vice president of public policy for the American Lung Association of the Northeast. A previous version of this story had an incorrect title.

Send questions/comments to the editors.