First of two parts: read part two here.

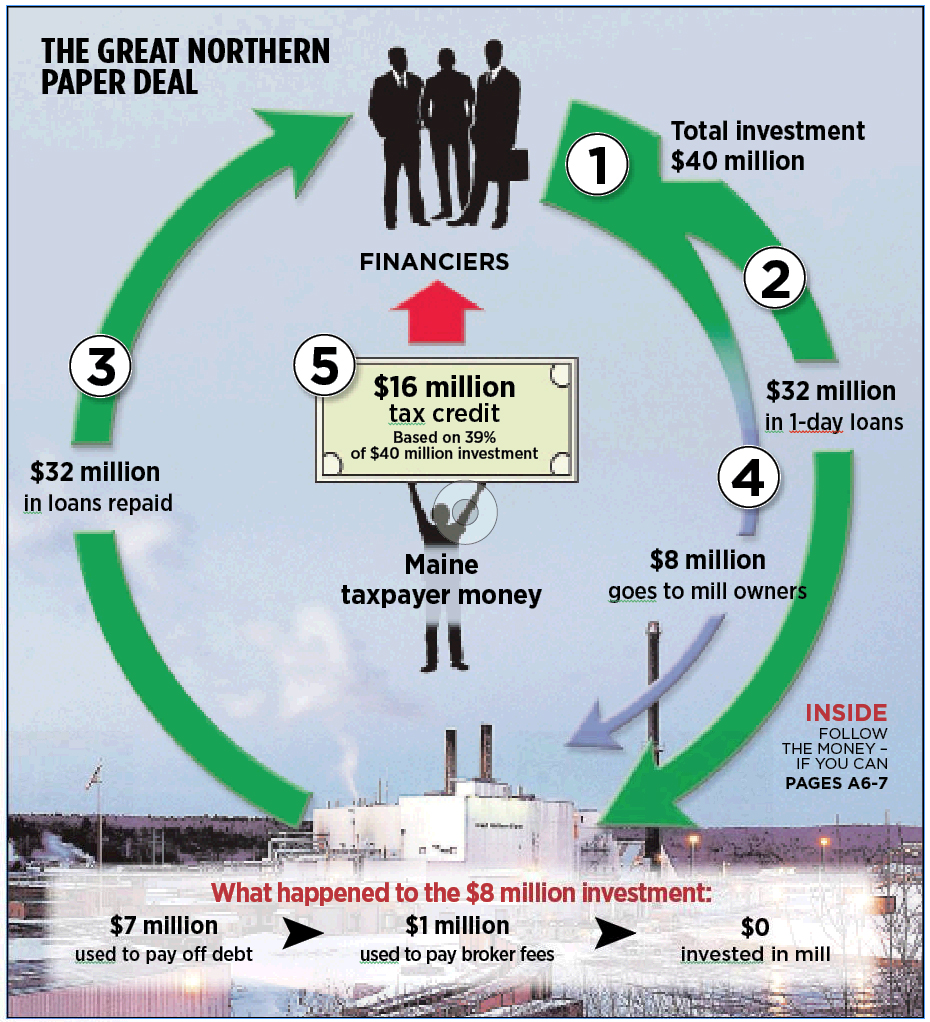

Sometime this year, the state of Maine will cut two checks worth a total of $2.8 million and mail them to out-of-state investors. Next year, it will send two more checks, worth $3.2 million, to the same recipients. It will repeat that process for the next three years until roughly $16 million of taxpayer money has been withdrawn from Maine’s General Fund.

This payout of taxpayer dollars through 2019 will make whole a commitment the state made in December 2012 to encourage what was – on paper – touted as a $40 million investment in the resurgence of the Great Northern Paper mill in East Millinocket.

But the resurgence failed. A year after the investment was received, the mill’s owner, private equity firm Cate Street Capital of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, shuttered the mill and laid off more than 200 people. Great Northern filed for bankruptcy a few months later with more than $20 million in unpaid bills owed to local businesses, leaving many to wonder what happened to that $40 million investment that was supposed to save the mill.

The reality is most of that $40 million was a mirage.

Great Northern was the first to take advantage of a relatively new, and complex, state program called the Maine New Markets Capital Investment program, which provides tax credits to investors who back businesses in low-income communities. Tax credits can be used to reduce the amount of Maine income tax they owe. The tax credits are worth 39 percent of the total investment, so the investors in Great Northern received approximately $16 million in tax credits from the deal, which they could redeem over seven years.

But the program, which faced little debate when the Legislature created it in 2011, lacks accountability. After spending five months examining the Great Northern deal, including documents obtained through a Freedom of Access Act request, the Maine Sunday Telegram found that:

• By using a device known as a one-day loan, the deal’s brokers artificially inflated the value of the investment in order to return the largest amount of Maine taxpayer dollars to the investors.

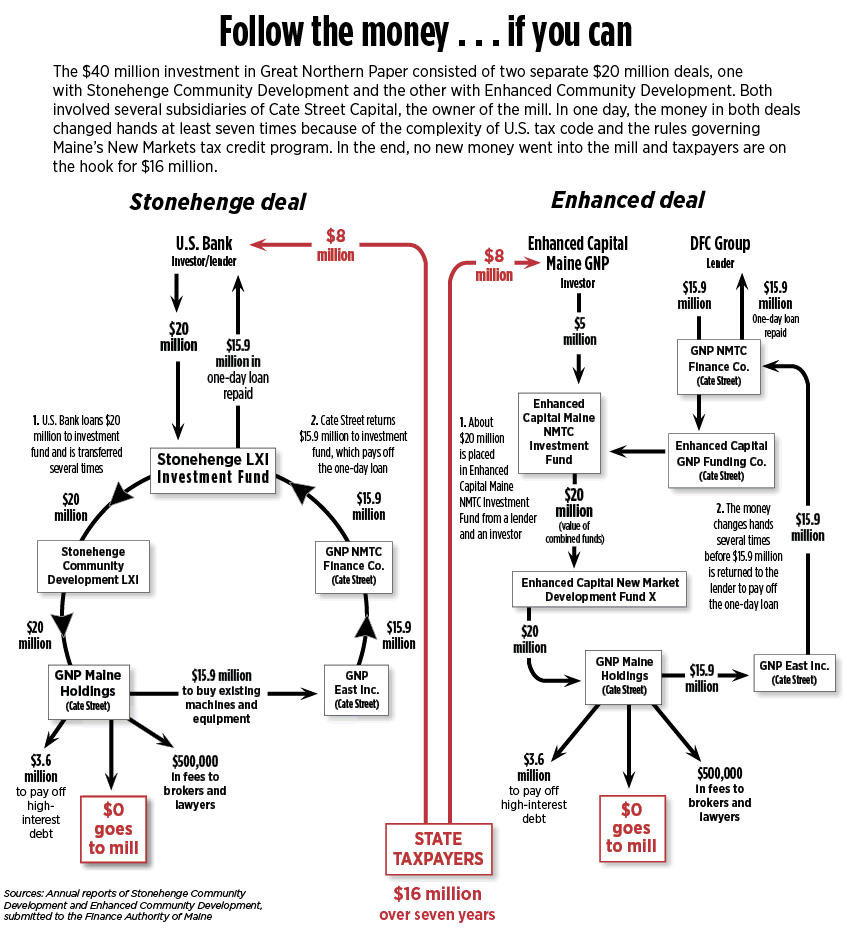

• The investment was $40 million only on paper. Most of the investment was an illusion, in which one Cate Street subsidiary used roughly $31.8 million of the investment to buy the mill’s paper machines and equipment from another Cate Street subsidiary, after which that $31.8 million was returned to the original lenders the same day.

• That means taxpayers will provide $16 million to the investors while Cate Street received only $8.2 million, most of which it used to reduce existing debt.

• The out-of-state financial firms that acted as middlemen in the deal, pocketing roughly $2 million in origination and brokerage fees, were the same ones that hired the lawyers and lobbyists who helped create Maine’s program.

• Two of those financial firms made a combined $16,000 in campaign contributions to the original sponsors of the bill.

• None of the money was invested in the mill, despite the intent of the program.

• Legislators and other decision makers in Augusta didn’t understand the complexities of the program when they approved it in 2011.

In the end, here’s what really happened: Two Louisiana financial firms arrived in Maine with a plan to create such a program, hired lawyers and lobbyists to get it passed in Augusta, then put together the Great Northern deal using one-day loans that made an $8 million loan look like a $40 million loan. While they claim they did this to leverage more investment, the result is that Maine’s taxpayers are going to pay $16 million to banks and investment firms that invested only half that amount. And all of it was legal.

“So were mortgage-backed securities that turned out to be backed by unsustainable mortgages,” said Dick Woodbury, an economist and former state legislator from Yarmouth, after the details of the deal were explained to him. “I’m really angry to hear how (the Maine New Markets tax credit program) has been used, and it has made me incredibly cynical about nearly any tax credit program and its potential for profiteering motives over genuine state interests.”

The Great Northern deal offers a cautionary tale about how experienced and sophisticated financiers and lawyers are able to manipulate a state tax-incentive program that receives little oversight from the Legislature.

At the time of the investment, Great Northern said it planned to use the money to upgrade the mill’s grinder room, convert the mill to run on natural gas instead of oil and facilitate a 30 percent increase in its annual production capacity, according to a January 2013 news release from one of the financial firms that brokered the deal, Enhanced Community Development of New Orleans.

But those projects never materialized. Through the use of two one-day loans, $31.8 million flowed in and out of the paper mill in a single day’s transaction that saw the money change hands no fewer than seven times, according to documents acquired by the Maine Sunday Telegram through a Freedom of Access Act request. The sole use of these funds – before they were returned to the original lenders – was to allow one Cate Street subsidiary to purchase the mill’s existing machinery and equipment from another Cate Street subsidiary.

At the end of the day, the paper machines changed hands on paper; the lenders that loaned the $31.8 million got their money back; Enhanced and the other broker, Stonehenge Community Development of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, pocketed $2 million in fees; and the equity investors – the people or funds that put up the $8.2 million that was not repaid as one-day loans – were promised $16 million in Maine tax credits, which are redeemable over seven years.

In other words, Maine’s taxpayers provided the equity investors, who faced little risk, with a $7.8 million profit. And despite the fact that the mill closed and went bankrupt, there’s no way for the state to wriggle out of its commitment to pay the investors the $16 million.

The law that created Maine’s New Markets tax credit program includes no requirement for how the recipient should use the money and – contrary to what some advocates claim – includes no mechanism to ensure the funds are invested in the business and therefore benefit its low-income community, as the law intended.

As a consequence, Maine taxpayers are on the hook to pay Great Northern’s investors $16 million through 2019 for investing $8.2 million in a mill that shuttered in 2014. And the people of East Millinocket have nothing to show for it.

HOW IT STARTED

The Maine Legislature created the Maine New Markets Capital Investment program in 2011 to encourage investment in businesses in low-income communities by offering “refundable” tax credits equal to 39 percent of the total investment. Investors who receive these tax credits are able to use them to reduce the amount of Maine income tax they pay over the course of seven years. However, if the investors don’t pay any taxes in Maine, the tax credits’ refundable nature means taxpayers will pay that investor the equivalent in cash from Maine’s General Fund.

Maine’s program is modeled on the federal New Markets Tax Credit program, which the U.S. Department of the Treasury says has funneled $40 billion into low-income communities throughout the country since 2000. The federal tax credits, also worth 39 percent of the investment, are not refundable – they would be worthless, for example, to a Canadian investor with no U.S. tax liability. The fact that Maine’s credits are refundable, which advocates claim is necessary to attract out-of-state investment, is a major difference from the federal program.

Maine lawmakers originally capped the amount of taxpayer money that would be doled out to investors in the form of tax credits at $97.5 million – which would leverage $250 million in total investment. As of December 2014, $71.8 million in tax credits had already been promised to investors for a total investment of $184 million, according to the Finance Authority of Maine, or FAME, which administers the program.

Since the cap is expected to be reached this year, lawmakers in Augusta are now considering a bill to double that cap, increasing the cost of the program in tax credits to $195 million and the total investment cap to $500 million.

The underlying logic behind the federal and state programs is that the upfront cost of the tax credits to taxpayers will lead to increased economic activity, which in the long run will generate enough new state or federal tax revenue to eventually exceed the original cost of the tax credits. For example, if a manufacturer receives a $20 million investment to finance the construction of a new equipment line and that leads to 20 new jobs, the community will gain from more jobs and a stronger local business, while the state will benefit from the increased personal and corporate income taxes generated by the business and its new employees.

At least, that’s how the lawmakers envisioned the program would work. But the use of one-day loans contradicts this premise by artificially inflating the value of the investments to a point that taxpayers are paying investors more than is ultimately invested in the business.

“I think the Legislature wasn’t aware, but not through lack of diligence,” said Christopher Roney, FAME’s general counsel and a critic of the use of one-day loans under the program. “I don’t think anyone contemplated this structure when (lawmakers) first approved it.”

FAME’s board has approved 10 projects under the Maine New Markets program, including the Great Northern deal. However, only seven deals have been completed as of this month. While several do not use one-day loans and meet the intent of the law, such as a $40 million investment in the new St. Croix Tissue mill in Washington County, at least four have used the one-day loan tactic. Roney supports the program but not the use of one-day loans. FAME has proposed an amendment that would essentially get rid of one-day loans.

The key players behind these deals are financial middlemen that act as brokers, bringing together investors who want tax credits with businesses in economically distressed areas looking for investment. These are not your normal banks or lending institutions, but in most cases specialized firms that focus on tax credit financing. In the federal New Markets program these middlemen are known as community development entities, or CDEs, a term also used in the Maine program.

The federal program also has its critics.

“Essentially, it just facilitates a sort of crony capitalism,” said William McBride, chief economist at the Tax Foundation, a right-leaning think tank. “A lot of these highly targeted tax credit programs are a way to funnel cash out of the general coffers and into some very, very select special interests.”

The fact that Maine made its tax credits refundable means the program is “extra dangerous,” McBride said.

The Maine program limits participation to CDEs that have received “multiple rounds” of tax credits under the federal program. That restriction was written by the same financing agencies, including Stonehenge, and lawyers who brought the New Markets program to Maine initially and now benefit from it.

FAME accepted six CDEs into the Maine program. The only Maine-based CDE is CEI Capital Management LLC, the for-profit subsidiary of Wiscasset-based Coastal Enterprises Inc. FAME gave each CDE a promise from the state that it could provide $16.25 million in tax credits to investors once they broker a deal in a low-income community. “Low-income” is determined by the median income or unemployment level of a Census tract. Large swaths of northern, central and eastern Maine qualify as eligible under the program, as well as small pockets in southern Maine, including in downtown Portland.

The CDEs use that promise of tax credits to entice investors to put money into their funds. The CDEs then look for businesses in low-income areas to invest in.

They found one in Great Northern Paper.

$16 MILLION FOR A DAY’S WORK

Cate Street Capital purchased the troubled paper mill in East Millinocket for $1 from Brookfield Asset Management in August 2011 and two months later returned 200 workers to their jobs making paper. As a name for its new papermaking subsidiary, Cate Street resurrected the Great Northern Paper moniker, made famous by the original company bearing that name that built the East Millinocket mill in 1906 and operated it for nearly a century before filing for bankruptcy in 2000.

The mill was a major employer in the Katahdin region of the state, an area beset with high poverty and few employment opportunities. Cate Street claimed it had spent more than $30 million on the mill since its purchase, including the acquisition of a high-interest $10 million loan, but it needed more money for upgrades to make it more competitive in an increasingly international market.

Stonehenge Community Development and Enhanced Community Development each promised $20 million for a total investment of $40 million. Because neither of these entities agreed to speak about the deal, it’s not clear how they became involved with Great Northern Paper. (The law originally capped individual investments at $10 million, but it was later amended at the request of Cate Street, which also wanted to use the program to raise funds for another subsidiary, Thermogen, to allow investments up to $40 million if the project promises to create or retain at least 200 jobs.)

The investors in the deal – those entities that had provided the funds to Stonehenge and Enhanced – were U.S. Bank, one of the country’s largest banks, and Vulcan Capital, the Seattle investment firm started by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen.

According to the annual reports filed by Stonehenge and Enhanced, U.S. Bank and Vulcan – represented as U.S. Bancorp Community Development Corp. and Enhanced Capital Maine GNP LLC, respectively – each invested approximately $4.1 million, for a total of $8.2 million. The rest of the $40 million total investment came in the form of the aforementioned one-day loans that were returned to the original lenders the same day.

Whether U.S. Bank and Vulcan still possess their Maine tax credits is unclear. While Maine law prevents tax credits from being bought and sold, the investor’s equity stake in the CDE’s investment fund, which comes with the benefit of tax credits, can be.

It can’t be proven because tax records are confidential, but it’s believed that neither U.S. Bank nor Vulcan, which will each receive about $8 million in tax credits, has any Maine income tax liability and so would receive cash refunds from Maine Revenue Services.

A spokesperson for Vulcan did not respond to repeated attempts by phone and email for comment.

Shera Dalin, a spokeswoman for U.S. Bank, would not confirm whether the bank possesses the tax credits, nor would she disclose whether U.S. Bank has any Maine tax liability, which would determine if the tax credits go toward offsetting its tax bill or could be refunded for cash.

“Unfortunately, I’m not going to be able to give you any information or comment about that,” Dalin said.

Michael Allen, associate commissioner for tax policy at Maine Revenue Services, declined to say who holds the tax credits because taxpayer information is confidential.

“Well, they file a (tax) return and receive a benefit from the state, a refund of some sort, and that’s confidential taxpayer information according to Title 36,” Allen said. “Sorry about that. Just following the law.”

ANATOMY OF A DEAL

Roney, FAME’s general counsel, admits to being “a little troubled” when the Great Northern investment deal first came across his desk. It was Roney who wrote the rules – based on the legislative language – governing the tax credit program and is tasked with reviewing the proposed projects and advising FAME’s board, which makes the ultimate decision on awarding tax credits.

He was unsettled by a number of issues.

First was that Great Northern said it would use a portion of the investment to pay back a high-interest loan of $10 million the company secured in 2011 when it reopened the mill. The company argued that since the proceeds of that loan were spent on capital expenditures at the mill, using the state’s tax credit program retroactively to settle that debt should be allowed. In a memo to FAME’s board dated Dec. 18, 2012, Roney warned about setting a precedent that would require it to treat refinancing past expenditures the same as funding future investments.

That, however, was not Roney’s biggest problem with the deal.

The bigger problem was that of the $40 million, Great Northern wanted to use roughly 75 percent of it to purchase assets the mill already owned, then immediately funnel the money back to the original lenders.

“No funds are actually used to purchase additional goods or services, or to construct additional facilities. Existing assets are changing hands among related entities,” Roney wrote to FAME’s board in the same memo.

Here’s how Cate Street, Stonehenge, and Enhanced accomplished that: First, Cate Street created a new entity called GNP Maine Holdings LLC to receive the $40 million investment. That entity then paid the $31.8 million to GNP East Inc., the existing Cate Street-controlled entity that owned the mill, to buy the paper machines and equipment. After the deal, GNP East was left owning only the land. (Both entities eventually filed for bankruptcy.)

After selling its equipment to its sister subsidiary, GNP East passed the sale proceeds to another Cate Street-controlled entity – this one called GNP NMTC Finance Co. – which then funneled the $31.8 million back to the original lenders, according to documents provided to FAME’s board.

The money changed hands eight times in Enhanced’s portion of the deal and seven times in Stonehenge’s deal, at least in part because of the complexity of the U.S. tax code and rules governing Maine’s New Markets program.

When Roney and FAME’s staff voiced concern over the deal’s structure, Chris Howard, the attorney from the Portland law firm Pierce Atwood who helped create the program and represented Stonehenge, Enhanced and Cate Street in the deal, argued that the use of one-day loans would be eligible under the federal program, so should be under the Maine program, as well.

The federal program permits one-day loans, which financiers say are a legitimate way to refinance past expenditures. But federal regulators don’t vet each investment deal as is done in Maine. The Community Development Financial Institutions Fund, which administers the federal New Markets program, only reviews past deals described in CDEs’ annual reports. Because of this, it’s unclear how often one-day loans are used in the federal program to artificially inflate the value of an investment.

Though this complex deal structure was presented to FAME board members, Anthony Armstrong, a member of the board at the time, said he still believed that people didn’t understand the implications.

“I certainly was not aware of that at the time of the vote,” said Armstrong, president and owner of Maine Home Mortgage Corp. in Portland. “It’s that kind of complexity that I did not feel comfortable with. But I will say this: I don’t think anybody on the board understood that’s what was going to be going on.”

Patrick Murphy, president of Pan Atlantic SMS Group and a former FAME board member, also said he didn’t believe people understood what they were voting on. He has come to question the quality of the statute that created the program.

“I think somebody needs to call the Legislature to task for not doing their due diligence on this,” Murphy said. “To my knowledge, there was no proper debate, no one weighed in on it.”

PLAYING HARDBALL

Despite their concerns, Roney and FAME’s staff, “after a long and difficult analysis,” eventually recommended the board approve the $16 million in tax credits for the mill’s investors, though it attached certain conditions.

“This is clearly not the type of transaction that staff anticipated under the program,” Roney wrote to the board at the time. “However, given the importance of the transaction to the general viability of GNP and to free up future cash flow for future investments and realize widespread community benefits, staff came to the determination that a very liberal interpretation of the rule requirements was warranted in this unique situation.”

Roney was able to get a condition attached to the request that Cate Street invest at least $9 million of its own money in the mill over the next nine months, the difference between the roughly $30 million Cate Street claimed it initially invested and the value of the $40 million New Markets deal. The agreement was supported by a guaranty from one of Great Northern’s parent companies that it would repay a portion of the tax credits if it failed to make the $9 million investment.

After securing the agreement, FAME’s board approved the issuance of the tax credits in a vote of 10 in favor and zero opposed. Two members abstained, including Armstrong, who cited a business partner’s dealings with Pierce Atwood. The other abstention came from Raymond Nowak, who is currently serving as chairman of FAME’s board. Nowak declined to comment for this story.

“If I hadn’t abstained, I would have voted against it,” Armstrong said. “I’ll be honest with you. I could not see putting $40 million out of a ($250 million) allocation into one project in one part of the state.”

For brokering the Great Northern deal, Stonehenge and Enhanced received nearly $2 million in origination and transaction fees, not counting annual management fees, according to documents obtained through a Freedom of Access Act request. It’s not clear if those management fees are still being paid since Great Northern filed for bankruptcy.

Neither Thomas Adamek, Stonehenge’s president, nor Richard Montgomery, Enhanced’s managing director, responded to several requests for interviews.

It was Stonehenge, in fact, that brought the idea for a state-level New Markets program to Maine. Pierce Atwood’s Howard confirmed that it was Stonehenge that approached his firm about drafting the bill that would create the Maine New Markets Capital Investment program. And it was Stonehenge, Enhanced and another Louisiana financing firm, Advantage Capital Partners, that paid former Republican lawmaker Josh Tardy $18,000 to lobby on the bill’s behalf in Augusta, according to records from the Maine Ethics Commission.

When the Legislature’s Taxation Committee held a public hearing on the bill, which was sponsored by then-Senate President Kevin Raye, there was only glowing testimony for the program and its promises of attracting out-of-state investment and jobs.

“If this committee is looking for a proven model for attracting to Maine both new capital and additional investment through the federal New Markets Tax Credit program to grow jobs and tax revenue – and do it in a way that much more than pays for itself – then I suspect you will like what you see in the state New Markets model,” said Ben Dupuy of Stonehenge, according to his written testimony. He went on to describe two investments Stonehenge had made in unnamed companies in Louisiana and Florida that created 220 jobs between them.

“Stonehenge, as well as a number of companies like Stonehenge, will bring new, private capital to Maine to finance projects like these if Maine enacts a state New Markets program,” Dupuy said.

Raye and two other co-sponsors of the original bill – Emily Cain, a Democrat from Orono, and Robert Nutting, a Republican from Oakland – played key roles in negotiating the adoption of the original bill’s language into the biennial budget. Since 2011, Stonehenge and its principal employees, including Adamek and Dupuy, have donated about $8,000 to Maine lawmakers, the bulk of which went to those involved in the passage of the program. Advantage Capital has donated about $3,500, all of which went to Raye, the bill’s co-sponsors and leadership.

Adam Goode, a Bangor Democrat who was at the time co-chairman of the Taxation Committee, voted to approve the bill but admitted not being clear on the details of how the program worked, such as the fact the tax credits are refundable. He chalked it up to legislators being overwhelmed with all the bills they must decide on.

“I, as tax chair, make decisions about the value of these programs based on incomplete knowledge, and there’s not actual evaluations and data,” he said. “It’s a lot of well-connected, powerful people saying they’ll hire or fire people based on it. They’re based on anecdotes and that’s a problem.”

Charlie Spies, CEO of CEI Capital Management, the only Maine-based CDE, also lobbied for the creation of the program.

“Maine will be making a long-term commitment to job growth and economic sustainability,” Spies said, according to his written testimony. “All projects, by definition within New Markets regulations, must create significant new improvements to the properties being financed.”

However, there is no provision in the state law that requires investments to be used for capital improvements or other specific purposes. The law defines a qualified low-income community investment simply as “any capital or equity investment in, or loan to, any qualified active low-income community business.” When asked about his testimony, Spies said through a representative that he stands by it.

Legislators are discussing the program anew this session because a bill has been introduced to increase the program’s lifetime investment cap from $250 million to $500 million. No one opposed the bill at its public hearing in early March, and it was unanimously approved by the labor and economic development committee April 8.

As for Great Northern’s promised $9 million investment over the ensuing year?

At the time of the FAME board’s vote, Great Northern submitted a 2013 capital spending plan that included roughly $9.2 million in upgrades to mill machinery and equipment – including $2.8 million to overhaul the grinding room and $2.7 million in upgrades for the paper room. Most of those improvements were never made.

In July 2014, after the mill was closed, Roney wrote a letter to Great Northern seeking proof that it had made the $9 million investment it had promised. In response, Robert Desrosiers, Great Northern’s director of finance, sent Roney a letter dated Aug. 27, 2014, detailing the company’s expenditures between Dec. 27, 2012, and Sept. 30, 2013, which he said satisfied its agreement with FAME. Desrosiers is also Cate Street’s director of compliance.

Desrosiers listed in his letter only $607,779 in capital expenditures in the mill during the time period. He claimed, however, that Great Northern met its commitment to the state because it incurred $9 million in net operating losses and spent $13 million on wood for the papermaking process.

Cate Street Capital officials did not respond to questions about the deal.

Roney still has reservations about how the deal went down. In response to the Great Northern deal and others that have since utilized the same one-day loan tactic, FAME has proposed an amendment to the bill that would effectively prohibit the use of one-day loans.

“I leave it to the Legislature to decide whether we ought to be mirroring the federal program or make modifications to our program to curtail that type of transaction,” Roney said.

COMPLEX, BUT LEGAL

These deals appear incredibly complex, a fact Kris Eimicke, one of the Pierce Atwood attorneys who worked on the GNP deal, blames on the federal tax code.

“It looks like the strategy on how to win the war in Afghanistan,” Eimicke said, referring to the deal flow chart provided to FAME’s board when it was considering the GNP deal. “But it looks more complicated than it is.”

Howard, the lead Pierce Atwood attorney who represented Cate Street, Stonehenge and Enhanced, defended the deal and said the use of a one-day loan to leverage a larger investment is not only allowed under the federal program but common in these types of deals.

“It’s a structure that has been used many, many times all over the country and in essence is utilizing New Markets tax credits to recapitalize the enterprise,” he said.

When asked to clarify how the deal recapitalizes the company -– in other words, provides it more capital – if funds are immediately used to pay back a one-day loan, Howard put it another way.

“The benefit of the structure is essentially that it enables us to maximize the tax equity” – the funds that come from investors like Vulcan and U.S. Bank – “that’s raised in connection with the transaction,” he said. “So the investment by the tax equity investors is higher as a result of the utilization of that leverage.”

In other words, the purpose of the $31.8 million that flowed in and out of the company and back to the original lenders in the same day was to enlarge the investment total on paper, which would return the maximum amount of tax credits to the investors. The idea is that the more tax credits are on the table, the more the equity investors would be willing to invest.

In regards to Great Northern using some of the proceeds to pay off its $10 million loan, Howard said that should be seen as a legitimate use of the program because it provides a huge advantage for a business.

“Now you have just enormously assisted that business with its overall cost of capital and that frees up capital within that business to be deployed to employment, new projects and investment in ongoing operations,” Howard said. “So reducing cost of capital is not a small thing.”

Eimicke also said the fact the investment kept the mill going and kept pumping personal income into the community for one more year shouldn’t be minimized.

“The one thing that gets lost … is that without this New Markets tax credit deal the mill would have shut down much, much earlier,” Eimicke says. “This really gave the mill a chance to survive and the fact that it didn’t … we’re very disappointed in that. I think the Cate Street company is – and obviously the state is – incredibly disappointed, but it wasn’t for lack of effort and it certainly wasn’t because of the New Markets tax credit transaction.”

EVALUATION WITH FRESH EYES

Because it’s a tax credit, and not a straight spending program that appears on the state budget every two years, the Maine New Markets tax credit program has received little oversight from the Maine Legislature since it was created, according to Goode.

“The people come to the tax committee to pass a tax credit for a specific reason,” he said. “Once it’s passed and in law, we don’t re-examine it.”

But an examination is expected.

The Legislature’s Office of Program Evaluation and Government Accountability is scheduled to scrutinize the state’s tax credit programs over the next year. Beth Aschroft, OPEGA’s director, said the New Markets program will be fully evaluated.

While the Great Northern deal may offer a cautionary tale, even its critics claim that the program itself has promise. They point to other projects funded under the program, such as a $40 million investment in November 2013 to the St. Croix Tissue mill in Washington County and the $10 million invested in Molnlycke in Brunswick, as evidence that it can work as envisioned.

“There’s nothing to say that most if not all of these other projects aren’t good projects,” said Armstrong, the former FAME board member.

However, the Great Northern deal wasn’t the only one that raised eyebrows at FAME. There have been others, including one investment in JSI Store Fixtures in Milo – this one brokered by Advantage Capital – that Roney and FAME staff recommended the board reject outright because, like the Great Northern deal, it used a one-day loan and none of the investment was actually slated to be used in the business. FAME’s board approved the deal anyway after Advantage threatened to pull its investments in two other Maine companies.

While advocates can hold up positive projects supported through New Markets deals, the structure and outcome of the Great Northern deal and others begs the question: Is the program good public policy?

Read part two: Shrewd financiers exploit unsophisticated Maine legislators on taxpayers’ dime.

Send questions/comments to the editors.