Maine is positioning itself as a player in Arctic politics, which could increase opportunities for Maine’s climate researchers and for businesses in the advanced materials, construction, marine transportation, renewable power and logistics sectors.

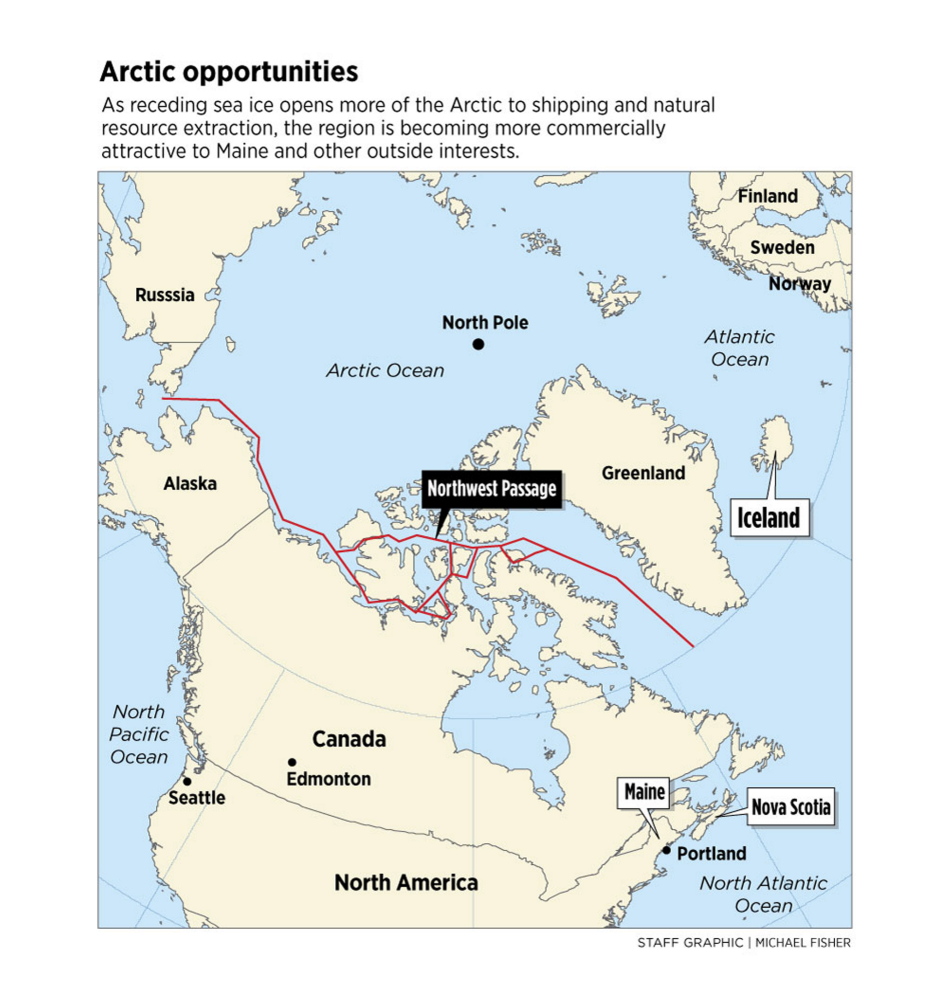

Maine’s interest in the Arctic may seem puzzling, considering its location some 1,500 miles south of the Arctic Circle. But the state’s geographic position at the northeast corner of the nation means ships passing through the Arctic reach Maine ports first, said Louie Porta, director of policy for The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Oceans North Canada campaign.

As Arctic sea ice continues to melt because of climate change, shipping lanes across the top of the world will become more viable, including potentially the Northwest Passage, a sea route along the northern coast of North America, said Porta, who grew up in Portland and now lives in Ottawa, Canada’s capital.

“From the U.S. perspective – as funny as it sounds – Portland is the port of entry to the Northwest Passage and Alaska is the place of exit,” he said.

Maine’s Arctic push comes as the U.S. prepares in April to assume the chairmanship of the Arctic Council, an intergovernmental forum for Arctic states and indigenous people.

Already, Washington, D.C., and some Arctic nations have taken notice. An Arctic Council working group will meet in Portland in September 2016, the first such meeting in the U.S. outside of Alaska. Maine is also under consideration to host a senior Arctic Council meeting that year, which would draw about 200 Arctic leaders and experts from the eight Arctic nations.

Until now, U.S. Arctic policy has been focused almost exclusively on Alaska and its surrounding waters: the North Pacific Ocean, the Bering and Chukchi seas and the Arctic Ocean. Yet with Maine’s interest, the U.S. has a new Arctic front opening up in the North Atlantic, with a focus more on trade and shipping rather than offshore oil production, said Mia Bennett, a Ph.D. student at the University of California, Los Angeles, who writes a news blog on the Arctic, cryopolitics.com.

Bennett sees Maine as playing a supporting role to Alaska when it comes to setting U.S. Arctic policy. She noted that Maine companies – Portland-based Ocean Renewable Power Co. and Westbrook-based Pika Energy – are working on innovative power projects that can benefit remote Arctic communities.

At both public and private levels in Maine, there’s an “almost entrepreneurial type of engagement with the Arctic,” she said.

PUBLIC, PRIVATE INTEREST IN ARCTIC

Maine’s Arctic push is happening on multiple fronts. On the national stage, Maine’s junior U.S. senator, Angus King, partnered this month with Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska to create an “Arctic caucus,” with the goal of prodding the United States to become a leader in guiding policy decisions that affect the Arctic.

King traveled a year ago to Barrow, Alaska, and sailed aboard a U.S. Navy nuclear submarine in the Arctic Ocean. When he returned to Washington, he saw Murkowski on the Senate floor.

“I said, ‘I want to be the Arctic senator.’ She said, ‘No, you can be an assistant Arctic senator,’ ” said King.

Gov. Paul LePage, meanwhile, has been forging the state’s ties with Iceland. He has supported the aggressive expansion of Portland’s shipping-container terminal, creating rail access and more cargo storage space, and is now accelerating plans to find a developer to build a multimillion-dollar cold storage warehouse on Portland’s waterfront.

Maine’s interest in the Arctic began two years ago when Iceland’s oldest shipping company, Eimskip, moved operations to Portland from Norfolk, Virginia.

A century ago, Portland billed itself as Canada’s ice-free port, but it’s now selling itself as the U.S. gateway to the high latitudes of the North Atlantic, an area that stretches from Newfoundland and Labrador to Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway and the northwest coast of Russia.

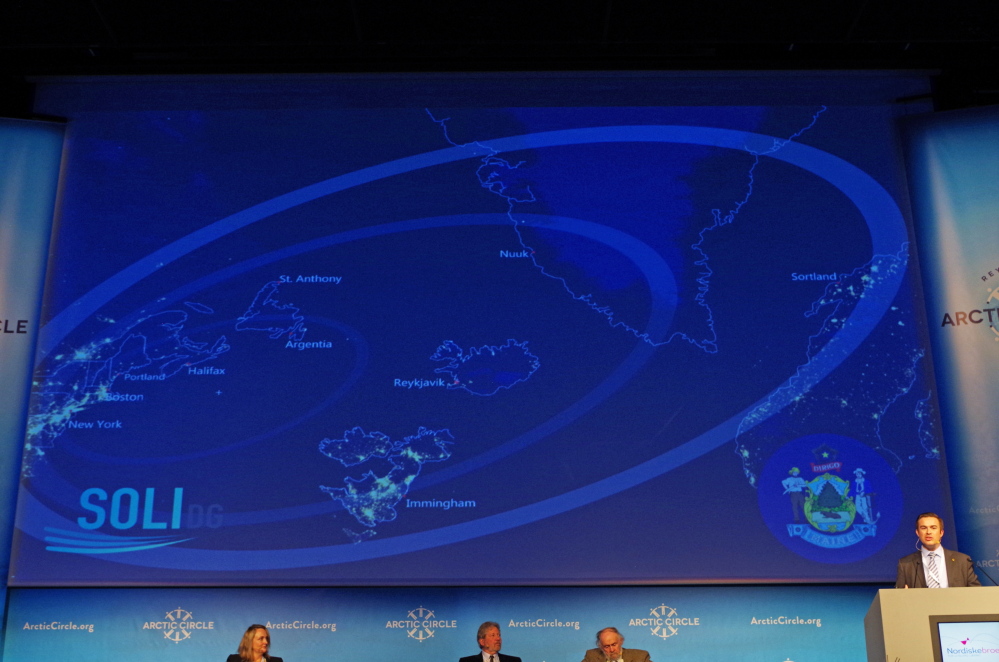

Speaking last October at an Arctic conference in Iceland, Patrick Arnold, president of Soli DG, a Maine company that operates Portland’s container terminal, displayed a map illustrating the cost of shipping goods from Portland to ports in the North Atlantic. The map showed that the cost of shipping a container from Portland to southern Norway is the same as shipping one by truck from Portland to Delaware.

“Maine has moved closer to the Arctic and Scandinavia as a result of Eimskip operating here and connecting Maine to trade routes,” Arnold said.

Eimskip’s arrival spurred the Maine International Trade Center, a quasi-state agency, in 2013 to create the Maine North Atlantic Development Office to promote trade between Maine and nations in the North Atlantic. The office’s director, Dana Eidsness, last month joined the U.S. delegation at an Arctic Council working group meeting in Akureyri, Iceland.

Also, Maine Maritime Academy is now partnering with the University of Alaska at Anchorage to develop maritime ice navigation and first responder courses for application in the Arctic Ocean.

In the private sector, one of the state’s most prominent business leaders, CEO Peter Vigue of the Pittsfield-based construction giant Cianbro Corp., has been building relationships in Iceland and Greenland, where he traveled extensively last year to scout potential projects. The company is able to build modular buildings at its Brewer facility and ship them by barge to remote working sites. Between 2010 and 2012, Cianbro built 22 modules in Brewer for a nickel-processing plant in Newfoundland.

So far, Portland is reaping the benefits from the Eimskip service, but Eastport stands to gain the most if the Northwest Passage route develops because it has the deepest natural harbor on the East Coast, Vigue said. He sees Eastport as the best port for large ships carrying bulk cargo, such as iron ore. He said the cargo can be shipped across the country on rail lines that can be brought into the port on a state-owned right-of-way.

“Maine is in an ideal position,” he said. “The opportunity is enormous.”

COMPETING FOR GATEWAY TO NORTH

But Maine is competing with Seattle, Washington, and Edmonton, Alberta – which is a rail hub with access to Vancouver and the Hudson Bay. Both cities are vying to position themselves as gateways to the north, said Sara French, a senior policy analyst at the Gordon Foundation, a Toronto-based philanthropic foundation that works to protect freshwater resources in northern Canada.

As declining sea ice levels open more of the Arctic to shipping and natural resource extraction, there is growing commercial interest in the Arctic, as well as growing interest by non-Arctic regions to supply those new commercial interests, she said.

“What we are seeing is a general trend as the Arctic becomes much more interesting to different regional players out of the Arctic,” she said.

In Alaska, Maine’s increased involvement is welcomed because it means more political clout and awareness in Washington, D.C., for Arctic issues, said Craig Fleener, an Arctic adviser in Alaska state government. Alaska has such a small population – and only three members in Congress – that Arctic issues are easily ignored there.

For example, Fleener said, Alaska needs help getting Congress to approve money for more large icebreakers – an issue that King has identified as one of his top priorities.

Russia has 40 icebreakers, with 11 more icebreakers in development or planning stages, according to the Council of Foreign Relations. The United States, by contrast, has only one icebreaker suitable for sustained Arctic operations, and that vessel primarily supports research in Antarctica.

King, who sits on the Senate Intelligence Committee and the Armed Services Committee, said icebreakers are crucial for shipping in the Arctic and also conducting rescue operations and securing U.S. strategic interests.

King said he’s also concerned about Russia’s increased military presence in the Arctic. Russia is building more than a dozen new airfields and adding four new combat brigades. As Arctic sea ice melts, he said, the U.S. must recalibrate its national security and economic strategies. King said his priority is to find ways that allow development to occur peacefully and minimize conflict.

DEPTH OF KNOWLEDGE IN MAINE

Maine’s involvement in Arctic policy raises the state’s profile internationally and helps companies already doing business in the Arctic find new customers, said Chris Sauer, president and CEO of Ocean Renewable Power Co., which is developing technology that allows remote Arctic villages to use fast-moving rivers to generate electricity. The company, which first developed tidal generation technology in Eastport, last summer installed a demonstration project on a river in Igiugig, Alaska. Pika Energy is developing energy transmission technology, also in Alaska.

Besides business interests in the Arctic, Maine has one of the nation’s oldest research institutes dedicated to understanding the climate – the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine, established 42 years ago. Moreover, researchers at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences and the Gulf of Maine Research Institute are studying the impact of climate change on oceans and marine life.

Although Maine is closer to Miami than the Arctic Circle, the tidal forces and currents of the Gulf of Maine have created a cold ocean environment that supports the same marine life as found in sub-Arctic seas. As the Arctic Ocean warms, the impact will be felt in Maine, said Paul Mayewski, director of the Climate Change Institute.

He noted that Maine’s involvement dates back to when Maine fishermen in the 1800s traveled to the Arctic to hunt whales and seals. Explorer Robert Peary, a graduate of Portland High School and Bowdoin College in Brunswick, claimed to be the first person to reach the North Pole in 1909. In 1920, boat-builders in East Boothbay built the Bowdoin, the only American schooner constructed specifically for Arctic exploration. The boat made 29 expeditions to the Arctic.

“We have this very long perspective on how the Arctic operates,” Mayewski said. “It is very important that Maine play a critical role.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.