I met World War II Army Air Forces veteran Alden “Al” Bonang, 89, last fall when I bought the farmhouse kitchen table for sale in the driveway of his Brunswick home. The table was a steal for $40, especially since Al Bonang and his grandson promptly delivered and reassembled it for us.

Thanks to Bonang, we no longer eat makeshift meals at the picnic table we brought inside to extend my Poppy and Nonny’s mid-century burl wood veneer round one. My lawyer-turned-carpenter father is building us a table for our dining room, but it’s a two-year process for the heavy Belgrade Lakes rock maple tree to be cut down, saw-milled, air-dried in my parents’ garage, and eventually, fashioned. Careful when you ask your dad to make you a table.

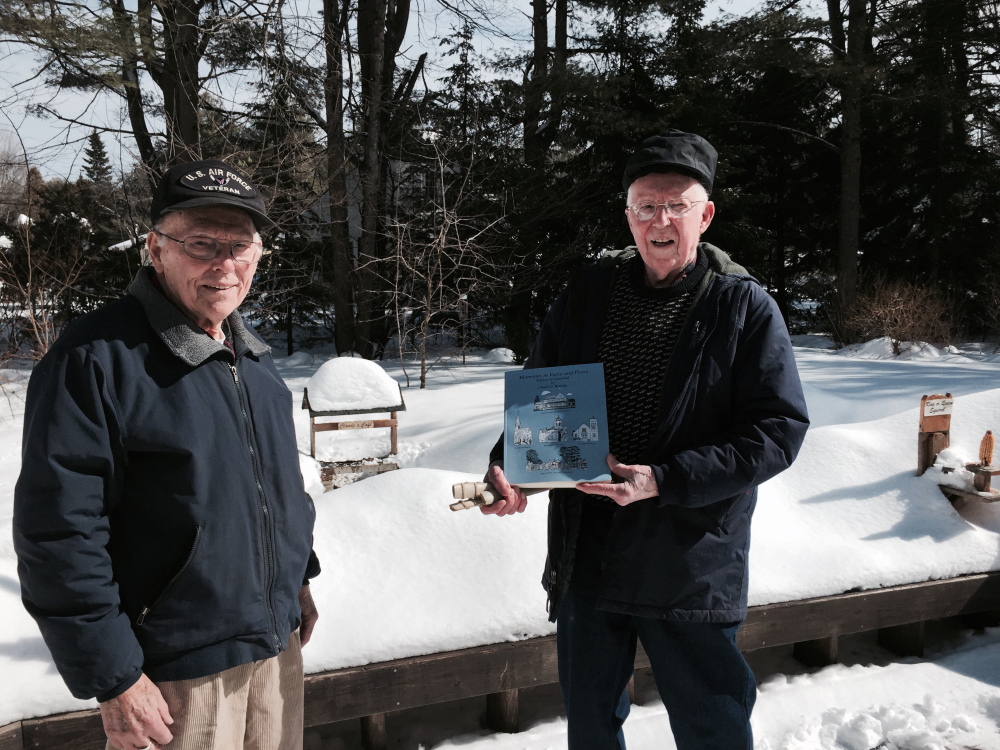

Since my grandparents have all died, I often find myself drawn into lengthy, fascinating conversations with people much older than I. When I told Al Bonang I was a journalist who writes about local agriculture and home cooking, he sold me on a copy of his 84-year-old younger brother Claude B. Bonang’s self-published book “Memories in Verse and Prose.” The book is rife with lyrical, humorous vignettes and sketches about growing up during the Great Depression and after in Brunswick in a French Canadian-Irish Catholic family of nine kids.

The Bonang brothers and I sat down together on a sunny Wednesday in early March to record a proper interview, just as the maple sap started to trickle. Talking with them made me miss my Poppy, my son Theo’s namesake, whose own World War II memories as a doctor on the Allies-occupied Christmas Island, a middle-of-nowhere central Pacific Ocean atoll. I recorded Poppy’s “medical memoirs” up until he died at 94.

To my delight, many of Claude Bonang’s warm memories centered on their Ma’s frugal yet filling food. His book reads like a more urban version of “Little House on the Prairie” and reminded me that today’s DIY hipsters are resurrecting traditional ways.

Locavore moms today can take a cue from Mrs. Bonang’s weekly meal plan. I’ve tried to give our family dinners more ritual and routine, say through Meatless Mondays, Tacos Tuesdays, fresh fish on Thursdays (when we had a Salt & Sea community-supported fishery share) and roast whole chicken on Sundays, boiling its carcass into stock for soup later in the week. But I’ve struggled to stick to my schedule.

Not Ma Bonang. In a poem that’s in the book, “Our Pantry, Ma, and Her Cooking,” Claude Bonang waxed nostalgic about the hours she spent making her own bread that she spread, come winter, with cretons, a hearty French Canadian pâté of ground pork. The Bonang weekly meal plan, as recounted by Claude:

“Each Thursday was hash day,

Leftovers from Friday through Wednesday.

Friday we always had some kind of fish;

Saturday was always a baked bean dish.

Our noon meal on Sunday was especially fine,

When on some kind of meat we’d usually dine –

Pot roast, pork roast, leg of lamb, beef brisket, meatloaf, or baked ham.”

Each spring, Papa Bonang spread their cow’s manure before planting the family garden with corn, beans (picked dry, and shelled on the porch to be baked with pork and molasses), carrots, tomatoes, beets, cucumbers (cut up for Ma’s chow-chow relish), parsnips and potatoes, the last further fertilized with manure “tea” and foraged seaweed.

The kids helped weed, kill potato bugs, hoe and battle rats for the eggs from the family’s flock of Rhode Island Reds; the hens yielded meat, too, “when their laying days were over.”

Claude also recollects “Pa’s home brew” beer, en vogue again in these do-it-yourself times, which “wet the whistles of many men, as well as those of a few women.” (Pa Bonang might be surprised by the ranks of female craft brewers in Maine today.)

Seafood was another staple. The family dug clams at Thomas Point Beach. And Pa wicker-trapped eels there, which Ma stewed or fried. At Bunganuc Landing on Maquoit Bay, the Bonangs bought cheap live crabs to shuck hot, later making sandwiches with the meat. And Pa built a backyard fireplace for boiling lobsters, purchased for just 25 cents per pound. Smelts ran so abundant “the stream seemed to be ‘boiling’ with them,” and the Bonangs caught them with their bare hands.

It turns out that Claude Bonang, a retired Brunswick High School biology teacher, is not only a poet, he’s also a virtuoso musician, playing on unusual instruments like his “rhythm bones,” castanet-like clappers he fashioned from a bag of cow ribs that he bought for $2 on butchering day from Bisson and Sons Meats in Topsham.

He cleaned and cut them, boiled the bones, dried them in the oven, then smoothed their rough edges with an electric rotary sander.

Since my Theo loves music, we postponed his nap on a recent Friday afternoon to take in Claude Bonang’s performance at Brunswick Respite Care for Alzheimer’s patients, where Bonang frequently plays, as he does at other local nursing homes. Theo sat mesmerized as Bonang played wooden maple spoons, a saw with a bow and those bones to cassette recordings of such tunes as “Try to Remember,” “Happy Days Are Here Again” and Rosemary Clooney’s “This Old House.”

“Hey, I’m going to play the bones when I grow up!” Theo shouted, running up to Bonang after the performance. “That was cool!” For now, though, the cow ribs are too thick for his small, chubby hands to grasp.

WARM MAPLE CREAM

The Bonang family kept a cow at their Bowker Street homestead, which was nestled in the pines next to Bowdoin College’s Whittier Field football stadium and track. Come winter, the Bonang kids would speed-skate and pull sleds in laps around the ice-covered track. Every spring, they collected maple sap from neighborhood trees that the family tapped. A favorite childhood treat was made from the new maple syrup and the cream that rose to the top of the milk. I updated the drink with a chai-like twist.

Serves 2

2 cups fresh cream from the top of unhomogenized milk or ordinary whole milk (or a combination)

Whole spices, such as cardamom, cinnamon or cloves, to taste

Freshly grated ginger root, to taste

2 tablespoons maple syrup

Pour the cream or milk into a saucepan on the stove. Add spices, if using, and ginger root and warm over medium heat, stirring occasionally until hot but not boiling. Add the maple syrup, stir to combine, pour into mugs and serve.

Laura McCandlish is a Brunswick-based food writer and radio producer. Follow her on Twitter @baltimoregon and read her blog at baltimoregon.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.