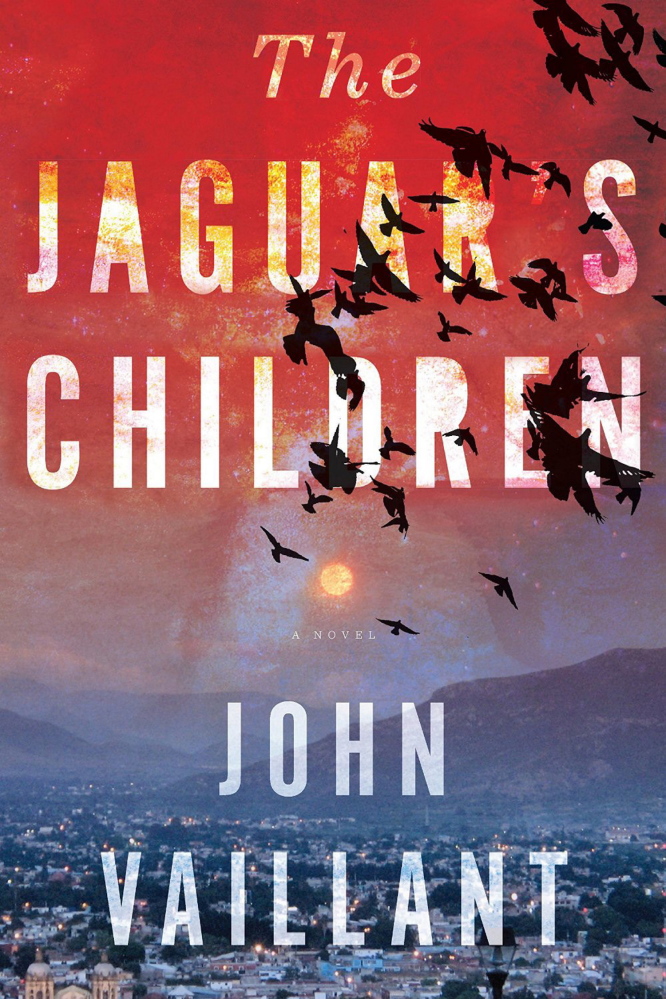

It’s hard to imagine a more viscerally horrific scenario than the one John Vaillant devises for his characters in “The Jaguar’s Children,” a brutally fascinating novel.

A group of Mexicans from Oaxaca (the southern province that was once the “corn basket” for much of the world) pays human-smuggling coyotes about $2,000 each to transport them to el Norte. The dozen or so men and women trustingly climb into the tank of a water truck and are sealed in. The narrator, Hector, and his buddy César hunker toward the back. Because it’s a short trip from their boarding point in Altar, Sonora, across the border to Arizona, each carries only a liter or so of water and meager possessions.

When the truck breaks down, the coyotes take off, promising to bring back a mechanic. So begins the waiting, detailed through Hector’s frantic text messages (are they going anywhere?), mental wanderings and reminiscences.

Days pass, with the conditions inside the truck becoming, well, what you’d expect, what with the heat and body fluids and lack of food or water. One more layer to this hell: Tanker trucks are curved. So the inmates can’t stand, can’t sit straight, can’t get comfortable in any position. Soon they begin to die.

Early in the ordeal, César gets badly injured. Hector tends to his friend as best he can, zealously holding back César’s water until he can’t help himself and begins to take sips. Add guilt to everything else.

Eventually, Hector essentially becomes as one with the jaguar totem – the jaguar is a god in Mayan culture – he carries with him: “When I woke up I was licking his face and I did not stop – could not. All the blood and sweat on him – his forehead, his eyes, his ear where it collected. I cleaned him like a cat. It is another world in here, where your mind watches from far away, and need and pain are the only gods you recognize.”

For anyone wanting to truly understand the onslaught of illegal Mexican immigration to the United States, look no further than this book. It’s a timely, gorgeously written example of how great fiction can prove more illuminating than even the most stirring nonfiction.

Vaillant has already made quite a name for himself with nonfiction that’s appeared in The New Yorker, National Geographic and Outside magazines, along with two award-winning nonfiction books, “The Tiger” and “The Golden Spruce.” Here, through his insight and literary grace, we can feel the immigrants’ hope and terror, and it’d be a hard person indeed who didn’t feel sympathy.

Vaillant takes no prisoners in his indictment of the North American Free Trade Agreement, which combined with Monsanto and other companies’ modification of corn crops, has pretty much destroyed the Oaxacan way of life. Mexico, “the birthplace of corn,” as Hector puts it, now imports corn and exports humans. “Backward, no?” He’s read in the newspaper that one out of three Oaxacans have gone to the United States. “So Oaxaca, you can say, is bleeding men.”

Vaillant also makes heated points about where resources go in sniffing out “the enemy.” “When those Greeks were hiding in that horse they wanted to attack the city,” Hector ponders, “and when the terrorists were hiding in those planes they wanted to attack the country, but when Mexicanos hide in a truck, what do they want to do? They want to pick the lettuce. And cut your grass. There are brave fighters in my country, I swear, but most of them are dead or working for the narcos.”

The author and his protagonist even dare to ponder a pie-in-the-sky solution, albeit with a wit that infuses the book, even at its darkest moments. It’s that spark that makes us love Hector and root for him, and perhaps to think his idea isn’t all that insane:

“Maybe this is our destiny – not for Mexico to lose her people or for America to lose her soul, but for all of us to come together – the United States of Améxica. It will be a new superpower, but with better food.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.