Gov. Paul LePage and his political allies are using traditional and social media to hammer Maine’s largest city as they pursue a seismic change in the way the state pays for General Assistance.

It’s a coordinated welfare-reform campaign with potentially major implications both for Portland’s finances and for the city’s growing population of asylum-seeking immigrants.

General Assistance represents $24.3 million – or 0.8 percent – of the Maine Department of Health and Human Services’ proposed $3.2 billion budget for the next two fiscal years. Yet how DHHS allocates that $24.3 million in General Assistance funds is consuming a disproportionate share of the debate over a department that accounts for half of the state’s $6.3 billion overall budget.

And Portland is in the administration’s cross hairs.

“Portland is the outlier in the state when it comes to General Assistance,” LePage told hosts Ric Tyler and George Hale on their WVOM radio show in Bangor last week.

“Portland is absolutely an outlier,” DHHS Commissioner Mary Mayhew said Wednesday on MBPN’s “Maine Calling” program.

“While other cities in Maine behaved responsibly with welfare payments, Portland saw a gravy train,” Matt Gagnon, CEO of the conservative Maine Heritage Policy Center, wrote in a blog titled “Portland’s welfare problem.”

Politics and political priorities are clearly driving the Portland-centric focus. Welfare reform topped the Republican governor’s agenda during both of his successful gubernatorial campaigns, and targeting the largely Democratic city’s fast-growing General Assistance program is likely an easy sell among LePage’s supporters in rural, conservative and less-affluent communities.

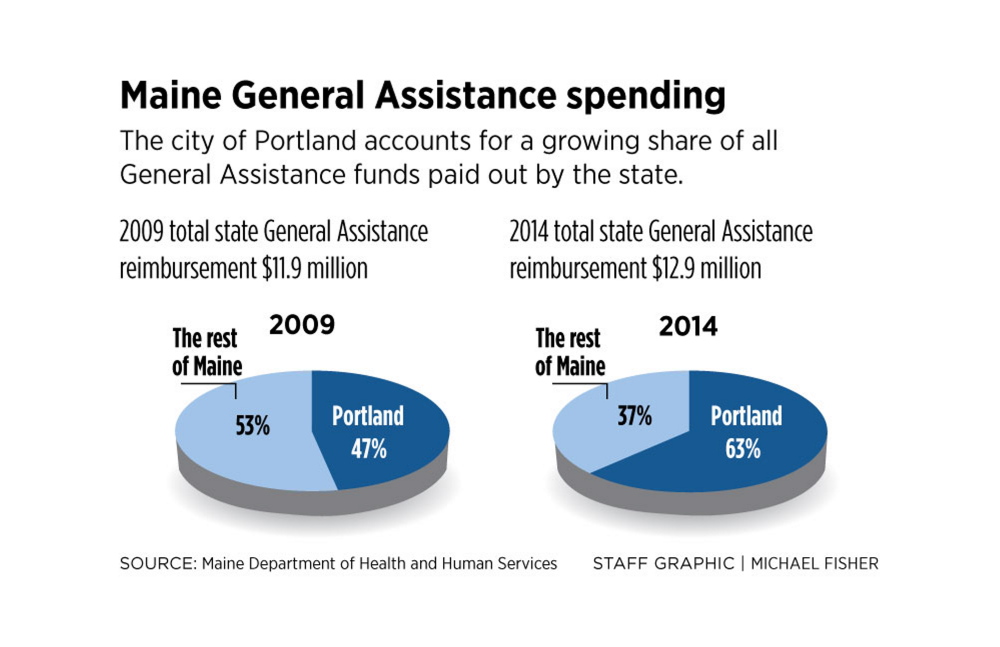

There is no disputing that Portland’s General Assistance program has ballooned, increasing from $5.6 million in 2009 to more than $10 million last year. That surge comes at a time when many other towns are spending less on the welfare program thanks to an improving economy, and, as a result, Portland, which has total municipal expenditures of $221 million, is responsible for most of the growth in state spending on General Assistance.

The reasons behind the increase are complex, however, and subject to political interpretation.

Portland officials cite three primary factors behind the surge: a dramatic increase in asylum-seeking immigrants settling in the city; rising demand for homeless shelter beds; and rental housing costs that have jumped 88 percent since 2009.

Among the three, the largest cost driver appears to be Portland’s status as a destination for immigrants fleeing war and political turmoil elsewhere – in other words, asylum seekers who typically do not qualify for federal assistance. The number of General Assistance recipients living in Portland on legal immigration visas increased by 297 percent between fiscal years 2011 and 2014 while immigrants categorized as “asylum pending” increased by 228 percent. At the same time, the number of other General Assistance clients in the city fell by 27 percent.

“The population mix is very different than it was in the past,” said Dawn Stiles, director of health and human services for the city.

The city’s elected officials, meanwhile, accuse the LePage administration of waging a political smear campaign against Portland.

“Why the administration would want to make things more difficult for the largest city in the state – and some would say the economic engine of the state – is baffling to me,” said Jon Hinck, a Portland City Council member and former Democratic state lawmaker who is an outspoken critic of LePage. “It is not going to help Portland and it is not going to help the state of Maine.”

THE CITY AS POSTER CHILD

General Assistance, often referred to as simply GA, is the state- and munipality-financed temporary welfare program that provides emergency vouchers for housing, food, fuel and other basic needs. Portland doled out roughly $10 million of the $18 million in GA payments distributed statewide in 2014 and received $8 million of the $12.9 million in state reimbursements.

Now, the LePage administration is casting the city as the poster child for why Maine needs to rewrite the GA reimbursement formula as part of the budget proposal he has submitted to the Legislature. The $5.4 million saved under the proposed changes would be used to reduce the number of disabled or elderly people on waiting lists for public services, according to the administration.

Currently, the state pays 50 percent of GA expenditures for all communities except Portland, Bangor and Lewiston. In those three cities, once GA spending crosses a certain threshold, the state pays 90 percent of costs and the cities pay the remaining 10 percent. Portland’s spending is such that it typically takes only three months of a fiscal year for the city to reach the point where the state begins to pick up 90 percent of GA costs.

DHHS officials have said repeatedly that this formula creates a “perverse incentive” for Portland and the other two cities to hit the 90 percent trigger and then offers no incentive to control later spending.

DHHS wants to effectively flip the reimbursement formula, paying 90 percent of communities’ costs initially but then dropping to a 10 percent reimbursement rate after communities cross a new threshold – in this case, when program costs reach 40 percent of the previous six-year average.

Bangor is projected to take a $588,000 hit while Lewiston would lose $45,000, according to DHHS figures.

But LePage and DHHS officials have made clear the change is aimed squarely at Portland, which stands to lose at least $4.3 million in state dollars if the Legislature approves the new reimbursement formula. Additional GA eligibility changes aimed at reducing welfare benefits to non-citizen immigrants will cost the city more than $1 million.

“Portland clearly will be the loser in this equation,” Mayhew said in a Feb. 7 interview on WGAN radio in South Portland. “But we have to change this equation and force more integrity in the management of General Assistance, specifically in the city of Portland.”

THE SOCIAL MEDIA EFFECT

The administration’s criticism has been reinforced in social media, such as the Twitter account operated by DHHS communications director David Sorensen, and on the DHHS Facebook page. The spokesman for the agency has tweeted repeatedly on the GA topic, such as a post Thursday in which Sorensen drew attention to letters to the editor of the Portland Press Herald. “Drop excuses, find solutions for Portland’s General Assistance costs.”

On Tuesday and Wednesday, Sorensen made two other Twitter posts on GA, directing his followers to a critical article published by a blog associated with the Maine Heritage Policy Center; and promoting DHHS Commissioner Mayhew’s appearance on a Maine Public Broadcasting Network call-in radio show with a statement that Portland “is absolutely a GA outlier, has concerns about method of eligibility determination.”

Mayhew and other DHHS officials have repeatedly accused Portland of being “overly generous” with its GA program and of failing to properly check the eligibility of welfare applicants. To bolster that argument, DHHS officials compared GA expenditures against the number of people living in poverty, as defined by federal income standards, in Portland, Lewiston and Bangor. The result is that Portland spends an average of about $750 per year in GA for each of the 13,350 people living in poverty in the city. That’s nearly three times as much as Bangor, which spends $287 on each of 7,560 people living in poverty, and eight times as much as Lewiston, which spends $96 for each of 7,813 people living in poverty.

But Portland officials said it’s inappropriate to compare poverty levels with GA expenditures, as many residents who meet the federal poverty standard don’t receive General Assistance. Also, neither Lewiston nor Bangor have experienced the dramatic influx of asylum seekers settling in Portland.

City officials also reject DHHS officials’ portrayal of Portland’s GA program, pointing out that the state agency audits the city’s program annually and did not have concerns until last year.

“We run the program following the same statutes and guidelines as every other community in the state,” said Portland Mayor Michael Brennan. “I find it particularly disappointing that the department started issuing statements about how we are mismanaging the program and we are being overly generous because there is nothing to substantiate that.”

Roughly 80 percent of Portland’s GA payouts go toward housing. For the first three months of the current fiscal year, Portland issued $1.3 million in vouchers to help recipients pay for rent, plus $715,000 for housing at homeless shelters. Roughly 15 percent paid for food, with the remainder divided among medications, utilities and personal items.

Portland’s long-standing practice of presuming that anyone staying at a city homeless shelter is eligible for GA has irked DHHS officials, who accuse the city of “inappropriately” billing the state for shelter operation costs. However, the city counters that it has consistently passed DHHS audits; that it follows shelter procedures established by DHHS in the early 1990s; and that the eligibility form used for shelter residents was developed in collaboration with DHHS and approved by the agency in 1996.

DHHS has been auditing Portland’s GA program since April, and in a Portland Press Herald op-ed published Saturday, Mayhew said the department has “serious concerns” about how Portland determines GA eligibility. However, DHHS has not released the results of that audit.

ADDRESSING ASYLUM SEEKERS

The proposed change to the reimbursement formula is just the latest front in a lengthy legal and political battle between the LePage administration and the city of Portland over General Assistance.

The two sides are awaiting a court decision on a DHHS directive issued last June declaring that the state would no longer reimburse municipalities for General Assistance provided to so-called “undocumented immigrants,” another policy change aimed squarely at Portland. The term “undocumented,” which immigrant advocacy groups dislike, includes both immigrants living illegally in the state – believed to be a small number in Maine – as well as immigrants who are legally protected from deportation while they apply for asylum.

Portland’s growing popularity among asylum seekers – combined with a growing federal immigration backlog – is straining both the city’s purse strings and city leaders’ political relationship with the LePage administration in Augusta.

During the past four years, Portland has witnessed a dramatic uptick in immigrants fleeing war or persecution in African nations such as Burundi, Angola, Congo and Rwanda.

Unlike refugees who apply for resettlement in the U.S. through an official resettlement program, asylum seekers typically arrive in Maine with valid visas, then apply for asylum after their visas expire. Federal law excludes asylum seekers and other “non-qualified” immigrants from receiving federal welfare benefits such as food stamps and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

Asylum seekers are often well-educated or higher-skilled individuals in their home countries, but are barred from even requesting a work permit in the U.S. for six months after they apply for asylum. As a result, most depend on General Assistance or charity to support themselves before they are legally allowed to work.

In fiscal year 2011, immigrants with visas or whose asylum applications were still pending accounted for 11 percent of Portland’s GA caseload. Three years later, those two groups accounted for 40 percent of the city’s roughly 1,900 GA cases.

CITY’S PROGRAM AS WEDGE ISSUE

DHHS officials rarely mention Portland’s population of asylum seekers when discussing the growth in Portland’s GA expenditures, even though the influx of immigrants is the largest driver of the increase. In her Press Herald op-ed, Mayhew did not mention the city’s asylum seekers.

Instead, the department has focused largely on the dollar figures alone and the fact that Portland consumed a 63 percent slice of the state’s total GA reimbursement pie last year, up from 47 percent in 2009.

“Governor LePage and his administration believe strongly in helping those truly needy individuals who seek GA from municipalities,” reads a DHHS document distributed to the media titled “Research Memo: GA Reform.” “It’s also clear that state funds should be more available to all cities and towns, not just Portland. A person in need of a hand up in rural Maine is just as important to help as a similar individual in Portland.”

Such statements, combined with a seemingly well-coordinated social media campaign by the administration’s supporters, have led some to speculate that the administration is using Portland’s welfare program as a wedge issue to build support for the governor’s controversial budget in conservative areas.

The administration’s critics contend that DHHS’ focus on Portland’s $10 million General Assistance program ignores the city’s multibillion-dollar economic contribution to the state. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, the Portland-South Portland metropolitan area accounted for 50 percent of Maine’s $54.8 billion gross domestic product in 2013.

Sen. Justin Alfond, D-Portland, accused Mayhew of running DHHS “more like a politician than a commissioner” as she tries to pick winners and losers in budgets.

“Portland is Maine’s largest and most diverse city, and rather than looking at Portland through this lens, she has chosen to buy into stereotypes and perpetuate stigmas that serve no purpose other than to justify her political attacks,” Alfond said. “If you are a new immigrant or someone trying to get back on your feet, Portland’s job market and public transportation make it a livable and workable place to be. I’d rather we have a conversation about how to strengthen these advantages for folks rather than tear it down.”

Gagnon, the CEO of the conservative Maine Heritage Policy Center, who supports changing the GA reimbursement formula, acknowledged that Portland’s growing asylum-seeker population and status as a “service center” are driving up the city’s General Assistance costs.

“But it is so far out of alignment from where it should be that I don’t think that explains it,” Gagnon said. Instead, Gagnon hypothesized that Portland’s screening process is more lax than in other communities and is offering welfare benefits to far too many people. And while the state’s $24 million General Assistance budget is not a huge part of the governor’s $6.3 billion budget, Gagnon said $10 million here and $20 million there quickly add up to significant sums.

“Is the system set up to simply dole out money to people who ask for it? Or is the system set up to help people with their lives?” Gagnon said.

DEFYING DHHS ORDER HAS COSTS

Portland could be facing difficult financial and policy questions regardless of what happens to the governor’s proposal to change the GA reimbursement formula when his budget plan goes through the Legislature.

If a judge rules that the LePage administration followed proper procedure in eliminating state reimbursements for undocumented immigrants, that would place the full financial burden on Portland to cover the estimated $3 million in General Assistance granted to asylum seekers. Also, LePage has threatened to withhold all reimbursement to municipalities that defy DHHS’ order, which could cost the city $9 million out of its $221 million total municipal budget.

“I’m concerned about any undue burden falling on the taxpayers of the city of Portland,” said Hinck, the city councilor. “So if the result of this is taxpayers will take on a bigger burden, I would be very concerned about that and I would not go along with it very willingly.”

Brennan, a former Democratic state lawmaker serving his first term as Portland’s elected mayor, said that while he opposes LePage’s plan, he believes the long-term answer lies in Washington, DC. Brennan plans to request a meeting with LePage, city officials and members of Maine’s congressional delegation to discuss ways the federal government can expedite the processes for asylum seekers to receive work permits and have their asylum requests reviewed.

“General Assistance, I agree, is not a good way to assist people who are seeking asylum,” Brennan said. “But at this point, it is the only vehicle that we have. And if that program were not available, there would be literally hundreds of people in the city of Portland out on the streets who would have no other ways to support themselves.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.