Only a few pages into Anne P. Gass’s “Voting Down the Rose: Florence Brooks Whitehouse & Maine’s Fight for Woman Suffrage” and the reader, even with decades of study in the field of Maine history, is learning new, exciting information available nowhere else. At least, not unless one is game to read thousands of letters, documents and newspaper clippings left by Whitehouse (1869-1945) to her descendants, the Maine Historical Society, the Portland Public Library and other institutions throughout the country.

The author, Whitehouse’s great-grand-daughter, is never sentimental, for this is a true work of scholarship. Gass depicts not only the work of one Maine suffragist, but also the clash between the Maine Woman Suffrage Association, founded in 1874, and the radical National Woman’s Party of 1916.

Whitehouse was high society. Her father-in-law helped found the pioneering state suffrage association. But, when she shifted her active support to the national group and its leader, Alice Paul, her decision sent shivers through local upper-class society. Here is where “Voting Down the Rose” proves so valuable as social history. In 1918, a visiting young suffrage activist, Julia Emory, provides this thumbnail attitudinal image:

“Portland is great, but the people – gosh – they resemble mahogany furniture. They are so damned dignified. They are conservative, conceited, self-centered, self-conscious, and fifteen years behind the times, narrow to the limit and are ready to forgive most anything before they would condone the dreadful sin of youth and enthusiasm.”

To a large degree, this was what Florence Whitehouse found herself up against. She was a happily married, middle-aged mother of three and novelist. After attending an 1913 anti-suffrage lecture by Morrill Hamlin, the daughter of a Maine governor, Florence was taken aback. Speaking at the Congress Square Hotel, Hamlin had stated that women were not suited to the rough and tumble of politics, and besides, “if they needed a measure passed they could simply ask their men to vote for it.”

In short order, Florence, with full public support of her equally committed husband, was debating the anti-vote woman. But such female naysayers were a minor problem. As Gass shows, the Maine Woman Suffrage Association had been trying to pass voting and tax rights legislation since the 1880s but was caught in a perpetual “legislative shell game.” Sometimes the Maine Senate would pass the suffrage bill and the measure would be defeated in the House, only for the vote to be reversed the next time the measure came up. It was the old-boy, two-party system at its duplicitous worse, and the suffrage group seemed content to play fetch. Moreover, it did little to support a national referendum. In a clear, readable style, “Voting Down the Rose” unravels the complicated story and introduces us to fascinating individuals.

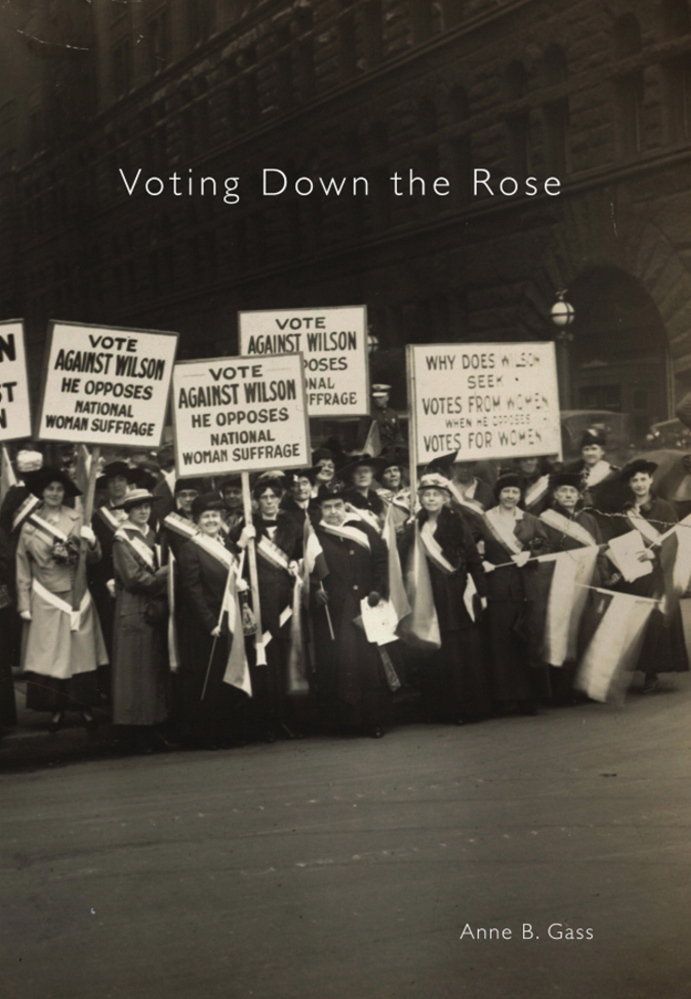

I have but few quibbles with the book. The rather bland cover, which shows suffrage picketers, the author’s name and the title “Voting Down the Rose,” without a subtitle means little to the casual observer. The reader will find that anti-suffrage women took the rose as their symbol with the suffragist using the jonquil – interesting but unknown to most of today’s readers. Also, for a book chock-a-block full of important facts not easily available to readers and researchers, “Voting Down the Rose” deserves a second edition with an index.

Otherwise, this book presents a biography charting the end of the struggle for ratification of the 19th Amendment in Maine. In 1919, Hamil had been correct about the “rough and tumble times” of politics, but for the majority of women it was worth the long struggle.

William David Barry is a local historian who has authored/co-authored seven books, including “Maine: The Wilder Side of New England” and “Deering: A Social and Architectural History.” He lives in Portland with his wife, Debra, and their cat, Nadine.

Send questions/comments to the editors.