Dustin and Natasha Colbry are exactly the kind of new farmers Maine has become known for on a national level. They’re 27, energetic and happy to be growing a business on 13 acres along a dirt road in their native Dover-Foxcroft. He grows vegetables for farmers markets and their CSA, she bakes with their farm-fresh eggs, and together they raise pigs. They’ve been in hog heaven. But when it comes to Internet connectivity, in their first year of farming they might as well have been living in the Dark Ages.

First, there was nothing but their cellphones, which got terrible reception. Verizon came out and set up a tower for them. Unsuccessful. The technician “was like, ‘Wow, there is nothing out there,'” Dustin Colbry remembered. They agreed to work with a jet pack, a mobile hot spot they ran through their Android phone. “We were just spending outrageous amounts of money just using our data plan for email and the typical things any business should be able to do on a wireless network,” he said. For them, that’s placing seed orders, advertising and managing their CSA (community supported agriculture), even something as simple as placing an order for the cute labels Natasha puts on her breads and pastries.

Finally last fall, Fairpoint showed up on the nearby route to Dexter, laying cable for high-speed Internet. “They’d say ‘We’re getting closer to you!'” Dustin Colbry recalled. Eventually, after the Colbrys spent about $400 clearing trees for the communications provider, they had a wireless connection inside the house. But just a few weeks ago, when they were having problems with the connection, a technician came out and did a speed test for them. “He told me it was horrible still,” Natasha Colbry said. “I guess beggars can’t be choosers?”

A movement is afoot to make sure that farmers don’t have to think of themselves as beggars when it comes to connectivity. As the Maine Legislature gets down to business in this new session, it will confront, by best estimates, up to 35 proposals to increase connectivity in Maine, whether in municipal or rural areas, or both. One of these will be backed by the Maine Farm Bureau and had its genesis with the Aroostook County Farm Bureau, where members at an August meeting voted unanimously to ask for a fivefold increase in funding for ConnectME, a state authority established to facilitate universal broadband to Mainers.

The bill, which will likely be introduced this month or early in March, is aimed at farmers like the Colbrys in Dover-Foxcroft; Sigrid Houlette in Westmanland, who has been known to negotiate her honey and fruit tree sales from a mobile phone standing on a hill behind her farm; and Jim Gerritsen in Bridgewater, whose potato seed farm is a tantalizing 3,200 feet and a daunting $12,000 bill away from high-speed Internet. But the hope is that it will provide motivation and means to future entrepreneurs in every far-flung corner in Maine, and help ease a connectivity problem that most agree is holding the state back economically.

In the United States, Maine ranks 37th in terms of access to broadband. Maine farmers in remote locations understand they’re a long way off the beaten track, even with the federally funded “Three Ring Binder,” a high-speed fiber optic cable that travels up through Northern Maine to Fort Kent and also along the Route 1 corridor. That’s Maine’s information superhighway, and it is 1,100 miles long. But some of Maine’s most innovative and unique farming is happening on what amounts to dirt roads off the byways that just barely connect to the superhighway. (Literally in the case of the Colbrys.) These farmers aren’t asking for the ability to stream Netflix – although that would be nice – they just want a chance to truly participate in Maine’s growing food economy.

POLITICAL BANDWIDTH

The sponsor of the Farm Bureau’s connectivity bill, Representative Bob Saucier (D-Presque Isle), is so passionate about the broadband issue that he’s also working on a $10 million bond project to expand the network in hopes of attracting business to the state. But he’s acutely aware of how many of his neighbors in Aroostook County (which along with Washington County accounts for the biggest service gaps in the state) need basic or improved Internet access. “There’s a lot of farmers that are not connected,” he said. He knows many of those 35 legislative proposals won’t come to fruition, but their sheer bulk gives him a sense of optimism; it’s a recognition of a need. “That is telling you we have a real problem,” Saucier said.

Saucier’s bill proposes an increase to ConnectME’s funding. While the authority has been the recipient of federal grants, that funding has come to an end and ConnectME, which has a staff of three, operates on a budget of about $1.4 million derived from a 0.25 percent surcharge on instate communications services. Translation, if you pay $100 for your cable bill, 25 cents goes to ConnectME, which passes on that money as grants to fund “last mile” infrastructure. Saucier, and the Farm Bureau, wants to see that amount go up fivefold, or to $1.25 for every $100 cable bill. He says it is a necessity. “You’ve heard of the ‘last mile’? Well, we’ve got the last five or six or seven or eight miles,” Saucier said, referring to Aroostook Co.

The major problem is the willingness of the major providers to serve what are seen as minor players. “They are doing the trunk lines,” Saucier said. “But they are real resistant to going to the real rural areas where they might have to lay several miles for a few customers.”

In Gerritsen’s case, it’s only three-fifths of a mile. His Wood Prairie Farm is in Bridgewater, a 36-square mile Aroostook Co. township with, he says, a total of eight households. Two are “bachelor loggers,” he said, the other six are affiliated with Wood Prairie Farm, a seed potato farm surrounded on three sides by wood lots. That protective isolation is critical to the nature of Gerritsen’s organic farming but it’s hell on a business where three-quarters of the orders are done online. FedEx and UPS don’t have trouble getting to Gerritsen every day, but he relies – or doesn’t – on a 10 year-old tower running on microwave technology for his Internet. In the last two years, it’s gotten slower and slower and some days, it just goes out. His provider has told him the technology has seen its heyday and is on the way out.

“There are days when we probably ought to just tell the crew to go home,” Gerritsen said.

The Three Ring Binder project brought fiber optic cable within a few miles and then Verizon extended it within 3,200 feet of Wood Prairie. “It’s as if we created I-95, and we don’t have any side roads or highways,” he said. Gerritsen said he has been told it would cost $12,000 to get it the rest of the way. “A business like ours, we can’t afford to bring that,” Gerritsen said. Moreover, he doesn’t think he should have to. “Nor should someone have to pay to bring in telephone lines,” he said. “This is a community investment and the community will benefit from it.”

NOT SMALL POTATOES

Wood Prairie’s annual sales are about $500,000.

“That’s not a dinky little business, is it?” said David Maxwell, program director for ConnectME Authority.

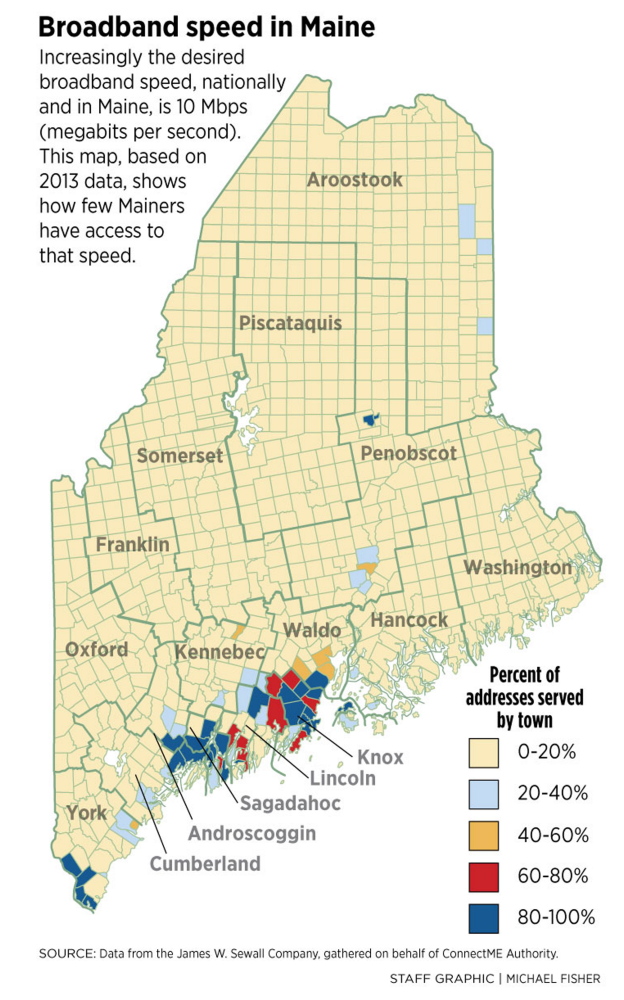

In January, ConnectME opted, with Gov. Paul LePage’s urging – his interest in the issue is another reason Saucier is optimistic – to push state standards for broadband in line with national goals. Before, any provider applying for a ConnectME grant to make those last mile connections had to provide broadband speeds of 1.5 megabits per second (Mbps). Now they’ll have to offer 10 Mbps. Only 11 percent of Maine households had at least 10 Mbps download speeds in 2013 (see map, Page S1) and the average broadband download speed, according to ConnectME, is 4.8 Mbps. The national average is 6.4 Mbps.

An indication of how high a standard 10 Mbps represents? In the urban center of Portland, it’s a rarity. Not because residents wouldn’t want it, but because providers don’t deliver it. It’s a reminder, Maxwell said, that broadband is not federally regulated. “People often view it as a right or a utility as they do electricity or water or so forth,” Maxwell said. “And therein lies the rub.”

At the authority’s current funding rate, with about $750,000 to distribute in grants each year, some estimate it would take 200 years to get all Mainers up to speed. “Several lifetimes,” Maxwell said.

At Tide Mill Organic Farm in Edmunds, where the ninth generation of farmers is in diapers, the farmers are hip enough to social media to have just completed an Indiegogo campaign to raise $25,000 toward a new chicken processing facility. And they do have broadband, but they’re about a quarter of a mile from the closest T1 line, a transmission line powerful enough to handle many households. Tide Mill’s operations incorporates four businesses ranging from a creamery to a woodlot, all heavily dependent on Internet access. There are simply too many of them on the line, using up the limited bandwidth they’ve got (“only two or three mega whatever they call it,” said matriarch Jane Bell). The only solution for better speeds is to pay to connect to the T1 line. They feel lucky to have what they’ve got, connectivity wise courtesy of Axiom, but “it is just painfully slow,” Bell said.

“We’ve had a good taste of it, but we want more,” she added.

Their inclination is the right one, technology experts say, and not just for farmers. Take Dwight Perkins, a retired businessman who used to work in financial services. He’s in the process of selling his suburban Boston home to move to Big Lake Township in Washington County. He’ll support his retirement there with a side business that requires a reliable connection, selling vintage outdoors equipment on eBay. Pioneer Broadband just connected him with fiber optic broadband in Big Lake Township. “Now instead of having intermittent service and a not-always-working phone, we now have state-of-the-art technology,” Perkins said. It can put residents of Maine’s most economically challenged counties on the same footing as say, Cumberland County, he said. “This is a blessing for everyone who is in business.”

Or wants to be. Like the new generation of farmers, many of whom grew up in Maine and didn’t want to leave it. Like the Colbrys. Their hometown may seem to be the kind of place where everybody knows each other’s business, but Natasha Colbry said when it comes to selling, connectivity is crucial. “In Dover-Foxcroft, we don’t really have that community place where we go,” she said. “The way we communicate is through the Internet.”

For those advocating for rural Maine’s connectivity, this issue should be as clear and as inviting as a well-lit home at the end of a dark country road.

“Imagine if we’d had the same attitude about broadband that we did about electrical lines,” Saucier said. “We have to connect everybody.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.