FREEPORT — There’s a lot of talk of the need to loosen Maine’s “home rule” system of strong local governments, wherein municipalities of a few hundred or thousand inhabitants each act as a tiny republic unto themselves, theoretically controlling everything from schools and land use planning to road plowing, fire station maintenance and the holding of elections. Governors – independent, Democratic and Republican – have argued that the state can’t afford such a fractured, redundant system of government, with 491 separate and often defiantly independent cities and towns.

“This kind of spending is unacceptable,” Republican Gov. Paul LePage said in his second inaugural address last month, before unveiling a plan to eliminate the state’s revenue-sharing agreement with municipalities. “Local control is great, but no one wants to pay for it. We will never be competitive until we learn to share services by working together,” he said.

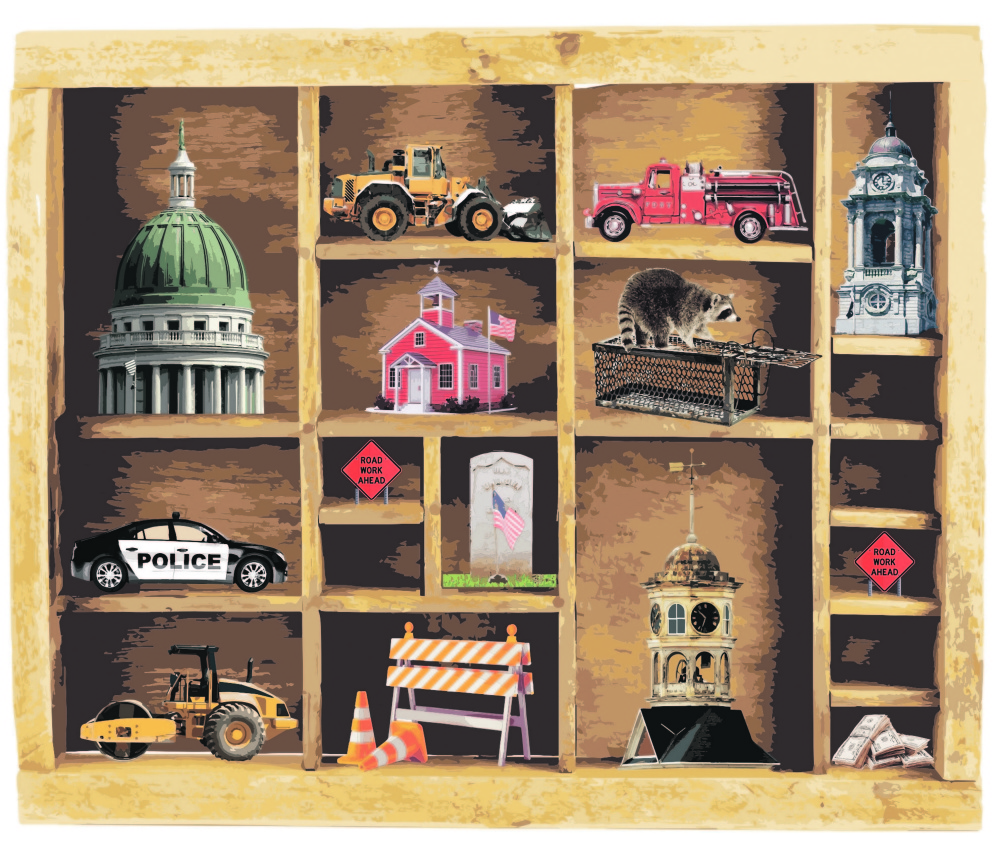

In the late 1990s, independent Gov. Angus King’s staff counted 91 fire trucks deployed within a 20-mile radius of the State House, each costing six figures and serving a population of just 95,000; there were 186 school districts serving 205,000 kids, meaning the average superintendent presided over just 1,200 students. Local control, King noted “comes at a high cost.” His successor, Democrat John Baldacci, pushed rural school districts to consolidate, while University of Southern Maine economist Charles Colgan warned that governments had to “collaborate or collapse.”

Yet we’ve resisted, be it to consolidate schools or jails, and when collaboration has been forced, it’s sometimes turned into an unhappy and expensive marriage; Freeport, Durham and Pownal, for example, have spent the past year trying to dissolve their nascent school union, discovering they disagree on what and how much to invest. Mainers, reformers have often discovered, are as committed to local control as they are to frugal, effective governance.

Understanding where this passion for local control comes from is essential to the ongoing discussion about changing it. For whatever the additional financial costs have been, it’s a system that’s delivered civic and budgetary benefits for nearly four centuries – benign features we may wish to conserve going forward.

Leave New England and certain swaths of the country settled by New Englanders, and you will find the country is not divided up into towns as we understand them here. Instead, a “town” or “city” is a compact incorporated area, a clump of self-governance usually floating in a vast unincorporated sea that doesn’t belong to a municipality at all. Most power is held by strong county governments, which control most aspects of life for anyone living outside incorporated cores. Only cities have the same level of power that every organized hamlet has in Maine.

New Englanders inherited this system from the early Puritans, who devised it to frustrate the centralization of power. Suspicious of archbishop and king alike, they vested civil and ecclesiastical authority in local congregations.

Believing themselves on a religious errand to build a more godly society in the American wilderness, the Puritans expected townspeople to work together toward the common good, governing themselves without the interference of bishops, kings or even county officials. Citizens came together in town meetings to act as miniature parliaments, giving direction to elected selectmen.

New Englanders didn’t fear their government because, in a very real sense, they were the government. Efforts to centralize power by royal officials – in the late 1680s and again in the mid-1770s – ran into intractable opposition including, in the latter instance, armed resistance by municipally organized and controlled militia units.

“The towns were controlled by their citizens – their ‘freemen’ – but to be a freeman, the law said you had to be a church member in good standing, which meant they’d be God-fearing, like-minded Puritans,” notes Emerson Baker, a historian at Salem State University who has written extensively on 17th-century New England. “It was a way of creating local control while still ensuring the towns would be in cultural lockstep with Boston.”

On foundation, each town immediately set aside a common town green and taxed themselves to build a meeting house and public school, the latter to ensure all adults could read the Bible. In Massachusetts, local control of schools and town meetings dates to the first days of colonization; this pattern was transferred to Maine after its forced annexation by the Bay Colony in the 1650s.

After the American Revolution, strong local government took on new importance. Many Americans shared Thomas Jefferson’s fears that the new republic would be destroyed from within, that a homegrown aristocracy would spring up to replace the one the revolution had just overthrown. Jefferson argued that the best way to avoid tyranny was to devolve as much power as possible to local communities, and that the most resilient democracy would be a network of small towns wherein people were self-employed producers – farmers, fishermen and tradesmen – and inherited privilege, by wealth or birth, was not to be tolerated.

Jefferson made his arguments from the Virginia Tidewater, a region with an aristocratic tradition and an almost total absence of towns, self-governing or otherwise. Although New Englanders were opposed to his political party, Jefferson extolled the virtues of their town meeting system, calling it “the wisest invention ever devised by the wit of man for the perfect exercise of self-government, and for its preservation.”

Foreign observers were impressed as well, recognizing that the hyper-localism of the New England system ensured civic engagement, trust, and self-confidence. “The New Englander is attached to his township because it is strong and independent,” French traveler Alexis de Tocqueville observed in the 1830s. “He shares in its management … he invests his ambition and his future in it (and) in the restricted sphere within his scope, he learns to rule society.”

These values of the early American republic are still a part of Maine’s homegrown culture. We’ve never given counties much power – although we’ve yet to abolish county government entirely as Rhode Island, Connecticut and most of Massachusetts have. And today over 90 percent of our municipalities still have a town meeting form of government, nearly 200 of them carrying on without as much as a town manager. In most of Maine, even today, budget items are approved directly, item by item, by a town’s assembled citizenry.

It’s a system that’s served us well, keeping a check on graft and corruption, and giving ordinary citizens considerable influence over what happens in their communities. Local control has kept government boondoggles to a minimum and forced those proposing high-impact projects to make their case to ordinary townspeople, not just county- or state-level politicos.

“There’s a reason why New Englanders are passionate about local control, and that’s because government at the local level works better,” says Eric Conrad of the Maine Municipal Association. “It’s more accountable because you know the people who are making the decisions because you see them at the grocery store and the post office counter. And it’s more cost-efficient as well, which may be counterintuitive.”

Indeed, it’s by no means axiomatic that consolidation makes things less expensive. When Envision Maine, the nonprofit headed by freelance Portland Press Herald columnist Alan Caron, undertook a study on how to improve the efficiency of Maine government, they came to the surprising conclusion that Maine towns deliver services 17 percent cheaper than other rural states. Brian Lee Crowley, who heads Canada’s conservative Macdonald-Laurier Institute, warned Mainers in these pages in 2010 that Nova Scotia’s municipal consolidation scheme had resulted not in lower costs, but higher ones.

“Regionalizing services can’t be done simply because it intuitively make sense, or for its own sake,” the Envision Maine study advised. “Absent that neutral, trusted data (on where consolidation will brings savings), it’s hard for anyone to move forward, and we end up with little more than competing anecdotes and strongly-held opinions.”

So strong local control has many merits, but it’s still in need of retrofitting. The central problem is that, unlike the 1690s or 1890s, we no longer live at the municipal level. Many of us sleep in one town, work in another, send the kids to school in a third and shop in a fourth. We live regionally, which means that we need to be able to plan and govern on a regional scale. One example: When Wal-Mart builds a supercenter, they’re thinking about a market of 50,000 people. Its effects will be felt over an entire county, and yet only the people of the town it happens to locate in have any say over where and how it is built. That’s the antithesis of local control.

There’s a strong case to be made to keep local control and home rule, but for citizens to frankly consider what “local” and “home” really mean. Clusters of towns – Boothbay, Boothbay Harbor and Southport; Millinocket, East Millinocket and Medway – are in it together; they ought to keep planning together, building trust, sharing services, revenue and administrators. But it’s got to be a voluntary, bottom-up movement.

In 1774, the British tried to centralize control, banning town meetings in Massachusetts and its District of Maine. Despite a spate of arrests and warnings from military governor Thomas Gage, towns defied the crown and held them anyway. “Damn ’em!” a frustrated Gage ultimately proclaimed. “I won’t do any thing about it unless His Majesty sends me more troops.”

In a state with strong local identities and civic traditions, local people really know best what partnerships will work and with whom. Forcing communities together from on high is unlikely to reduce costs, but is certain to spark resistance.

Send questions/comments to the editors.