Often, reading about the times in which the subject of a biography lived is as interesting as reading about the subject himself.

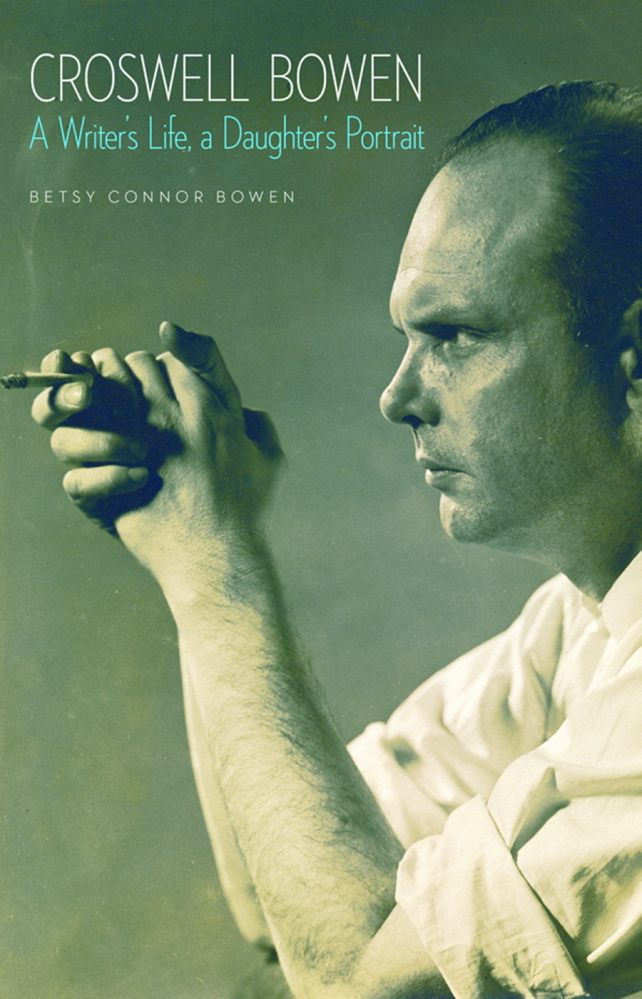

That is the case with “Croswell Bowen: A Writer’s Life, a Daughter’s Portrait,” by Betsy Connor Bowen of Winthrop.

Croswell Bowen (1905-1971) grew up in Toledo, Ohio, son of a wealthy real-estate developer, graduated from Choate and attended Yale University, dropping out when he had trouble dealing with being rejected by Skull and Bones, the elite social club. He finished his degree work at the Sorbonne in Paris but was still considered part of the Yale class of 1929.

What would have been the boring life of a spoiled rich kid transformed while he was touring Europe after graduation: His father lost his fortune as an indirect result of the stock market crash.

After he returned to the United States and was told there were no jobs on Wall Street, where he had intended to go to work, Bowen got a job with the International News Service in New York based on the credentials of being a Yale man and having one summer of reporting for the Toledo Blade.

Thus begins a good, not great, career as a journalist. He was beaten by police while covering a Communist rally, transferred to Washington to cover the State Department, fired for his aggressive questioning of Secretary of State Harold Stimson, returned to New York, where he did some reporting and hung out with the Greenwich Village writing set, his highlight an essay, “I Was a Rich Man’s Son” in Forum magazine.

Connor Bowen does a good job fleshing out her father during these formative years and creating a picture of a time of upheaval in America. She fills out some of the history by creating conversations as she thinks they might have occurred. These sections could have been omitted.

What really changed Bowen was his time as a photographer with the American Field Service, serving with British troops fighting in North Africa. He discovers the horrors of war but also his own vulnerability. His ailment first believed to be shell shock is finally diagnosed as polio.

Returning to the States, Bowen in time lands the most important job of his career, writing for PM, an alternative, liberal New York newspaper that accepted no advertising. Bowen wrote about, and the reader of the biography gains insights about, the House Un-American Activities Committee investigations, the formation of the United Nations and more.

When PM folded in 1948, Bowen moved to a staff position at The New Yorker, specializing in major crime figures and what turned them to crime, at a time when Bowen himself began to fear (correctly) that he was under investigation by the FBI for his liberal leanings.

The book here covers the disintegration of his family life as Bowen tries to continue doing important writing while failing to earn enough money to support his wife and children.

The daughter does not ignore her father’s shortcomings as she celebrates his successes. Rushing out to buy milk, Bowen accidentally backed his car over his son, killing him – which added to the depression that ended with Bowen leaving The New Yorker. One flaw in the book that sent me back to see if I had missed something has the son’s death being mentioned in the section about Bowen leaving The New Yorker but not fully explaining it until a later chapter.

The highlight of the four books published in Croswell Bowen’s lifetime is a 1959 biography of Pulitzer- and Nobel-prize winning dramatist Eugene O’Neill, whom Bowen met while writing a PM story. That book was a National Book Award finalist and a commercial success. It also covered O’Neill’s relations with his children. Bowen felt an empathy for O’Neill, whom he considered another Black Irishman, a Roman Catholic who had lost his faith.

The rest of his life Bowen wrote mostly for money, for commercial magazines and an advertising company, with occasional work similar to his early career. When Connor Bowen was an adult, he summed up his life to his daughter.

“He had, he would tell me wistfully, ‘lived in interesting times,’ taken part in their ‘action and passion,’ and ‘made a contribution.’ ” she writes.

What makes this book worth reading are “the interesting times” and the “action and passion.”

Tom Atwell is a freelance writer who lives in Cape Elizabeth. He can be reached at 767-2297 or at:

tomatwell@me.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.