SOUTH PORTLAND — A fungus that has killed bats by the millions in the Northeast continues to spread across the United States and into Canadian provinces bordering Maine, raising concerns about the survival of one of nature’s most effective methods of insect control.

But biologists and researchers from throughout New England who gathered this week in South Portland said that amid the gloom there are glimmers of hope that some bats will find a way – either naturally or with human help – to survive the white-nose syndrome epidemic.

“If you had asked me six or seven years ago, I would have been sure that we would have no bats whatsoever,” said Christina Kocer, regional coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s white-nose syndrome program in Massachusetts. “We are learning more every day. … So those of us who have been doing this for a long time really cling to that.”

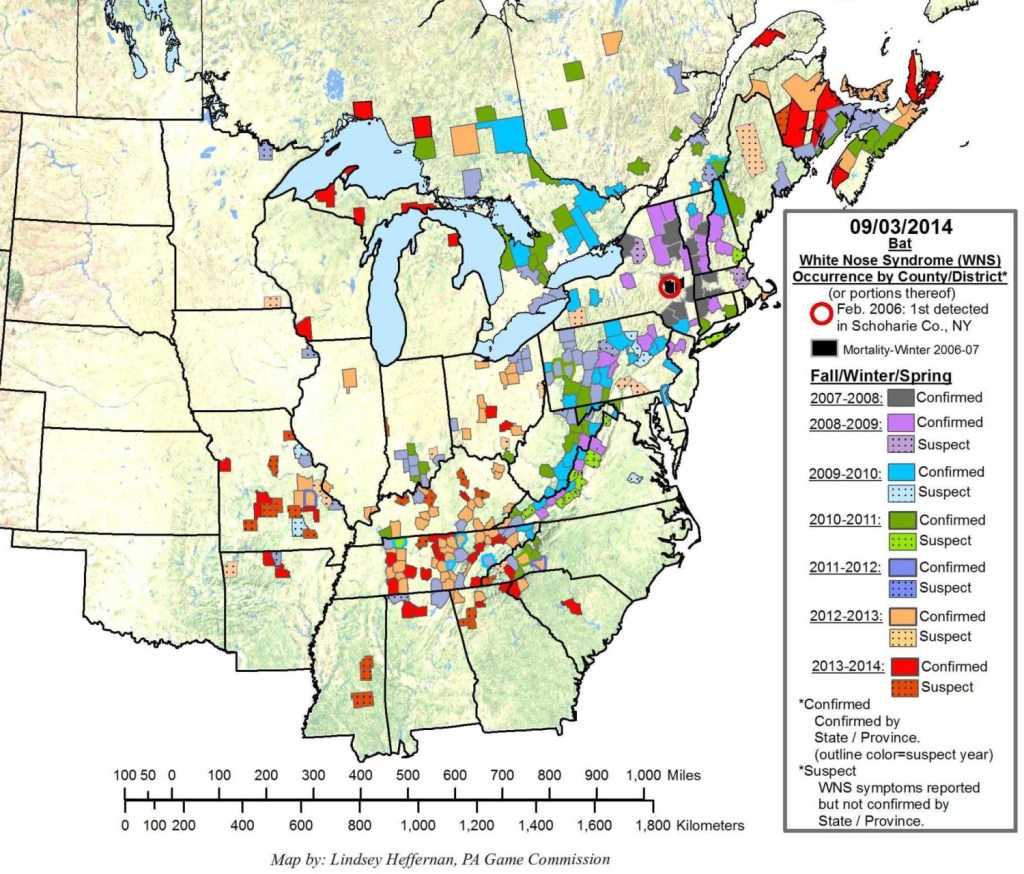

Since its discovery in a New York cave nine years ago, white-nose syndrome has rapidly spread throughout the Northeast and mountainous regions of the Southeast, oftentimes decimating local bat populations. It was first documented in Maine in 2011 and can now be found in 25 states and five Canadian provinces, including in areas along Maine’s border with New Brunswick and in Nova Scotia.

Bat mortality has been pegged at between 90 percent and 100 percent in some areas, including in some Maine surveys. Although maligned and feared by many people, bats are voracious bug eaters that occupy a key ecological niche, so scientists say the deaths of an estimated 5.5 million bats since 2006 is likely to have implications. Little brown bats, the species most commonly encountered by New Englanders before the recent die-offs, are capable of eating up to 1,000 mosquito-sized insects an hour.

Federal officials are considering whether to add the northern long-eared bat to the endangered species list.

RARE SIGHT IN MANY PLACES

Recent research out of the University of Wisconsin has suggested that the fungus first noticed as a white fuzzy coating on bats’ muzzles – hence the “white-nose syndrome” name – causes bats to essentially overheat during their winter hibernation. As a result, the bats burn through their fat reserves more rapidly, causing them to either starve or to freeze to death after they leave their place of hibernation midwinter in search of food.

Maine-specific research on bats is limited because the state is not home to the large hibernating caves, known as hibernacula, found in Vermont, New York, Pennsylvania and other states. Even so, bats have become a rare sight in many places in Maine where the nighttime summer air once teemed with the feeding mammals.

Wally Jakubas, who heads the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife’s mammal division, said netting surveys suggest that populations of the two more common species found in Maine, the little brown bat and northern long-eared bat, have declined by more than 90 percent.

“But there is a little bit of hope,” Kocer, the regional coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, told several hundred attendees of the New England Bat Working Group conference at the Doubletree Hotel in South Portland.

Some hard-hit populations of little brown bats have stabilized in recent years despite the continued presence of white-nose syndrome in their hibernacula, suggesting that some bats are developing resistance to the fungus. Some bats banded by biologists in Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Vermont are turning up in capture nets years later, which Kocer said is another positive sign. And scientists hope that the discovery of how the fungus is killing bats could help them devise ways to combat it.

All of that said, Kocer said researchers expect white-nose syndrome to continue to spread throughout North America, and the long-term implications of that spread remain unclear.

“I’m worried,” she said.

‘FRIGHTENING’ POPULATION DECLINE

Bruce Connery, a biologist at Acadia National Park, said he first noticed irregularities in Mount Desert Island’s bat population in fall 2011.Over the next several months, Connery received more than 70 reports from local residents who had found bats dead or dying in the middle of winter, leading to the first documented cases of white-nose syndrome in coastal Maine.

A little more than three years later, the number of bats he and other biologists capture is a fraction of what they once caught while conducting netting surveys on MDI. The area’s moth population, meanwhile, appears to have increased substantially based on what Connery sees at night.

“It’s pretty frightening because of (bats’) contribution to the ecosystem,” he said.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is expected to decide by April 1 whether to designate the northern long-eared bat as “threatened” or “endangered.” This could put any development projects in bat habitat under additional federal scrutiny. Inland Fisheries and Wildlife also is considering adding the northern long-eared and the little brown bat to Maine’s endangered species list.

Some agencies in Maine are not waiting for the federal decision.

Northern long-eared bats often roost underneath bridges and in trees, so the Maine Department of Transportation already has stepped up its surveys for bats at projects that are in the pipeline. The presence of the bats likely would not scuttle a project, but could force the department to take steps to minimize disturbance, such as waiting to clear trees when the bats are not present.

“We have to treat it as if it’s endangered … so we don’t have delays when the listing comes,” Eric Ham, a MDOT biologist told conference attendees.

Send questions/comments to the editors.