Richard Lobor’s family fled Sudan when he was a boy to escape the violence of civil war and the threat of execution.

But instead of finding safety in America, Lobor was shot in the head last month in the doorway of a Portland apartment, becoming the city’s only homicide victim this year.

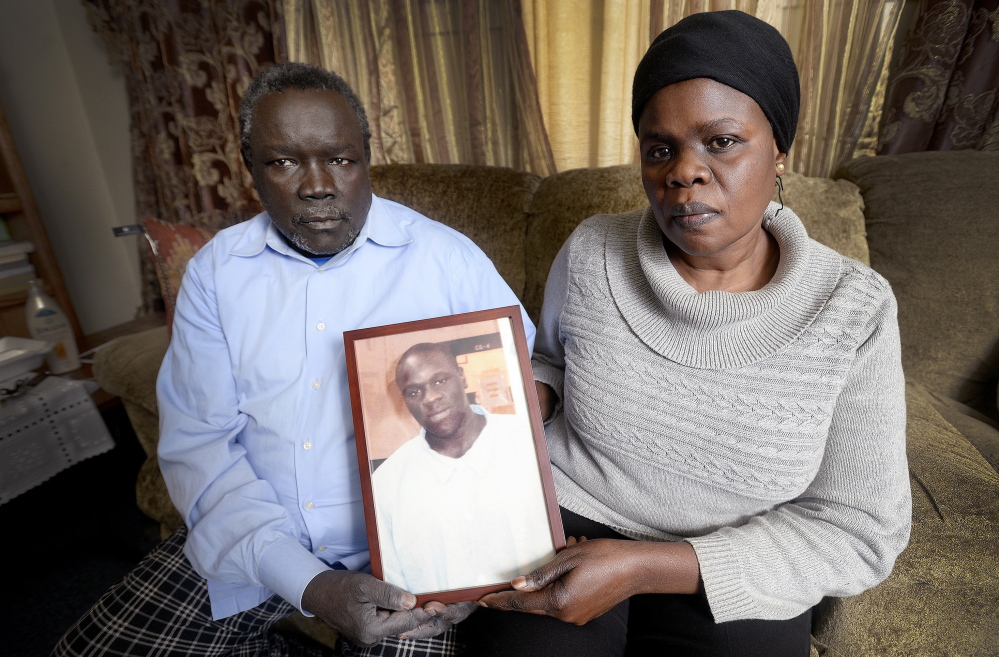

Lobor, who was 23, was the oldest of the family’s six children and had been expected, in accordance with Sudanese tradition, to become the head of the family soon. Now his parents, Robert Lobor and Christina Marring, are asking themselves as they grieve how things went so wrong in a country they thought would lead their children to prosperity and a better future.

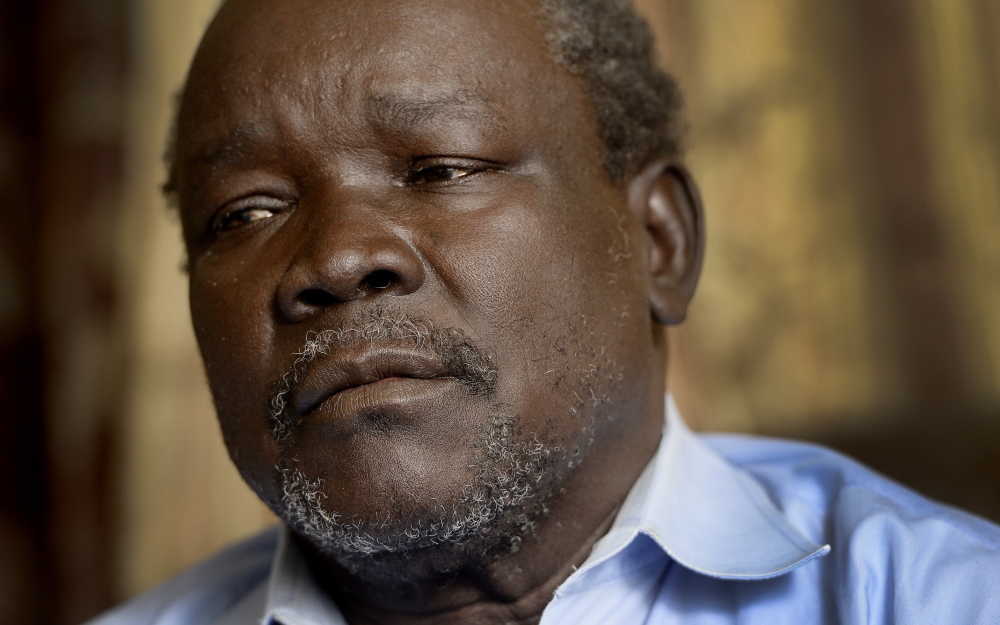

“It’s really a big shock to us, his death, really a big shock the way it happened. We didn’t expect that this would happen,” his father said in an interview last week in the family’s home on Munjoy Hill in Portland. “We came to this country for opportunity, like other people, looking for a better life.”

A ‘WONDERFUL KID’ WHO STRUGGLED

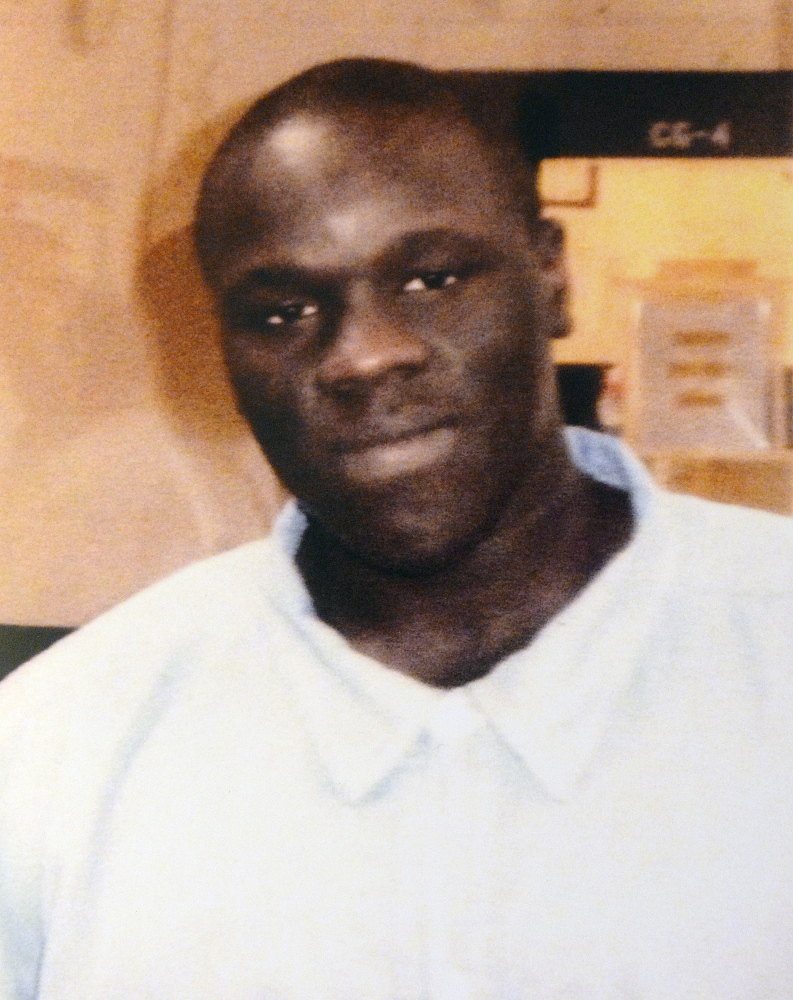

The promising future his parents hoped for had eluded Lobor, who was familiar to the Portland police officers now investigating his slaying. He spent most of his adult life in prison after being convicted of an armed robbery committed when he was 17, after years in the juvenile justice system. A lawyer who once represented Lobor described him as a kind and “wonderful kid” who loved his family but who struggled with the trauma of his early life and the fear of being a black man in a mostly white state.

Investigators have released few details about the fatal shooting, which was reported at 9:05 p.m. Nov. 21 at the Princeton Village apartment complex on Brighton Avenue. They have not identified a suspect.

“The investigation is very active, and detectives are working on this daily,” said Portland police Lt. James Sweatt.

Lobor was killed in the same apartment at 214 Brighton Ave. where police had responded a week before to a reported drug overdose, according to Portland police call logs.

But Sweatt said it was “very premature” to say whether Lobor’s death was drug-related, and that police are not making any assumptions.

Police have not yet responded to requests by the Portland Press Herald to release the report from the Nov. 14 drug overdose at the apartment and denied a request for the transcript of a 911 call made on the night that Lobor was killed.

CRIMINAL BEHAVIOR ESCALATED

The Lobors left Sudan at the height of political strife during the second civil war in the East African nation. They were Christians in a predominantly Muslim land.

Robert Lobor said he was not involved in the country’s warring factions, but felt his family was at risk. Rebels clashed frequently with government forces, and people often were executed if their allegiances were in doubt.

“They can kill you even if you are only a suspect,” he said. “So we left and came here to America.”

“It was very difficult for us because we are Christians,” said Marring, his wife.

The Lobors, with five young children at the time – their youngest was not yet born – escaped at first to Egypt, where they remained for nearly three years before the United Nations found them refuge in Maine.

Lobor was 12 when his family arrived in Portland on Nov. 22, 2003. He had completed the fifth and sixth grades in Egypt, and started seventh grade at King Middle School, his parents recalled.

As a young newcomer to Portland, he excelled. He did well academically and was an active athlete. He became a U.S. citizen after his parents went through the naturalization process.

But as a teenager, he began to struggle. A summary of his juvenile offenses, contained as part of his public adult records at the Cumberland County Courthouse in Portland, starts with four counts of assault, disorderly conduct, criminal use of a disabling chemical, and criminal mischief, before advancing to serious felonies when Lobor was 17.

“When he joined Portland High, I think that’s when the trouble started and with some of his friends. I was called to have a meeting with his principal,” his father said.

Lobor was first committed to the Long Creek Youth Development Center for juvenile offenders in September 2007, when he was 16.

By 17, after his release from the South Portland facility, Lobor was charged with armed robbery for holding up a Portland convenience store with a loaded handgun in his waistband. Though still a juvenile, he was charged as an adult because of the seriousness of the crime, and he pleaded guilty. He first served two years in prison, then three more after violating the terms of his probation.

Lobor was freed from correctional supervision for the first time in his adult life on July 3, when he was set free from the Maine State Prison in Warren. But what he did with his freedom is only partly clear to his family.

His parents said he had begun work at a construction job, making money, stepping up to his role as eldest son. His father is temporarily out of work as he struggles with diabetes. His mother is the family’s chief income earner, working as a housekeeper at Mercy Hospital in Portland. And seeing their son doing well gave them hope.

“Always he say like that, ‘If I find a good job, I’m going to buy a house.” That is the dream for Richard because he knew we would retire. And he would put the money to buy a house,” his mother said.

But he was also hanging out with friends he didn’t want his parents to know. He refused to tell his father the names of those friends or what they did even up to the day he was slain, Robert Lobor said.

“Friday at 4 o’clock, he came here with other friends, two people in the car, and outside he talked to me for a while, and then he left,” Robert Lobor said, recalling the last time he spoke to his son just hours before the fatal shooting. “On Saturday morning, 9 o’clock, I received a call. He told me that Richard was shot. When I got that news, it was a shock. I was falling down here. I was screaming here.”

‘DIDN’T KNOW WHERE HE FIT IN’

Attorney Gina Yamartino, who became Lobor’s friend after representing him as a juvenile, was driving on the night of Nov. 21 when one of his friends called her to say he had been killed. Yamartino said she was so shocked and in disbelief that she had to pull over.

“He was a wonderful, wonderful kid. I got to know him really well,” Yamartino said. “There was a lot to Richard.”

Although Yamartino was no longer Lobor’s attorney, she continued to stay in touch with him. She talked with him most recently less than three weeks before his death, to check up on him and to try to set up a time to have lunch together.

Yamartino spoke at her law office in Portland last week while sorting through a thick binder filled with scores of letters and cards that Lobor had sent her over the years. She read some of them aloud, as she pulled page after neatly handwritten page from envelopes.

“He remains one of those kids I will always carry around with me. He wanted very much to be what everyone wanted him to be. He was incredibly warm, really kind and really thoughtful,” she said. “I, to this moment, can tell you that he made a lasting impression on me. He was a kid who loved people, who loved his family, who loved the world and didn’t know where he fit in.”

Yamartino said Lobor was very smart and considerate, and had great potential. But he struggled with his early-life trauma as a refugee and with being mistreated because he was black.

She showed some letters in which Lobor talks about wanting to provide for his family and feeling like he let them down for getting in trouble. In another letter, he wrote to her about what it is like to be black.

Yamartino read that one aloud: “From Sudan to Egypt to Europe to America, I have to deal with racism. I have lived everywhere, and I don’t know where to go to fit in peacefully.”

Yamartino is still torn about how she and authorities handled the armed robbery case against Lobor. She now believes that moving him from the juvenile justice system to adult prison did him more harm than good.

In the robbery, Lobor entered the Big Apple store on Washington Avenue in Portland with a 9 mm handgun in his waistband, one round loaded in the chamber and two more in the clip, shortly after midnight on March 6, 2009.

Yamartino said Lobor was very intoxicated that night when he and another boy demanded money and blunt wraps – cigar wrappers often used to hold marijuana – from the store clerk.

Although she ultimately relented and allowed him to be prosecuted as an adult, after Lobor insisted to her that’s what he wanted, she said she still feels “like the system failed him.”

“I don’t think we fully understand – and how could we? – what his experiences were before he got here. I truly believe he suffered from a fair bit of trauma, and coming here wasn’t going to fix it all,” Yamartino said. “I think we have to think long and hard about kids coming from different countries and understand what their experiences were and honor those experiences as best we can.”

Yamartino said that although Lobor’s criminal record looks bad on paper, that doesn’t tell the story of who he was.

“I want to make sure that people understand that Richard really was an amazing kid,” she said. “He didn’t have a chance to be who he was supposed to be.”

SYSTEM INEXPERIENCED WITH REFUGEES

Christine Thibeault, the head of the juvenile division of the Cumberland County District Attorney’s Office, distinctly remembers prosecuting the armed robbery case against Lobor and coming to the decision to try him as an adult even though he was still a juvenile.

Thibeault disagreed that the system failed, as Yamartino said, but agrees that officials in the juvenile justice system in Maine have little background in how to deal with refugee children with traumatic backgrounds in war-torn countries.

She said that while authorities can be compassionate and recognize that youths like Lobor have a history of trauma, his behavior by 17 was “very risky to other people” and the juvenile justice system had been “ineffective” at changing that behavior.

“Obviously, public safety is our number one concern, and he was a juvenile who had not responded to intervention as best we could offer it. So we had no recourse,” Thibeault said. “In general, we don’t bind over individuals (to the adult criminal justice system) unless we believe they will continue to be a risk to the public and we don’t believe the juvenile justice system will be able to mitigate that risk.”

Thibeault said the vast majority of youths in the juvenile justice system are never committed to a detention facility. And of those committed, she seeks to have only a handful of those prosecuted as adults, so few that she knows them all by name, like Lobor.

“I don’t think we really understand how to deal with youth who come from countries that are experiencing war, famine and refugee camps,” she said.

Thibeault said those who work in juvenile justice in Maine are experienced in how to deal with childhood trauma from abuse and neglect, but have little background in treating trauma of refugee children.

“I wish we understood better how to intervene and redirect these young lives. We have a lot to learn,” she said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.