The first Englishmen to visit Maine had quite a shock.

It was May 14, 1602, and Bartholomew Gosnold’s crew had just made landfall after eight weeks at sea. Stretched before them was an uncharted land “full of faire trees” and a “shore full of white sand, only very stony or rocky,” a realm claimed by their king that a dozen years hence would be dubbed “New England” and an anchorage that is now either Cape Neddick or Cape Elizabeth.

As they approached the point of land, out came a French-built sailing vessel, “a Biscay shallop with saile and oars” manned by eight persons “whom we supposed to be Christians distressed,” as their captain wore a black waistcoat of English serge, breeches and cloth stockings, European shoes and a banded hat. Once the vessel came closer, however, the English explorers realized the shallop’s crew were Indians.

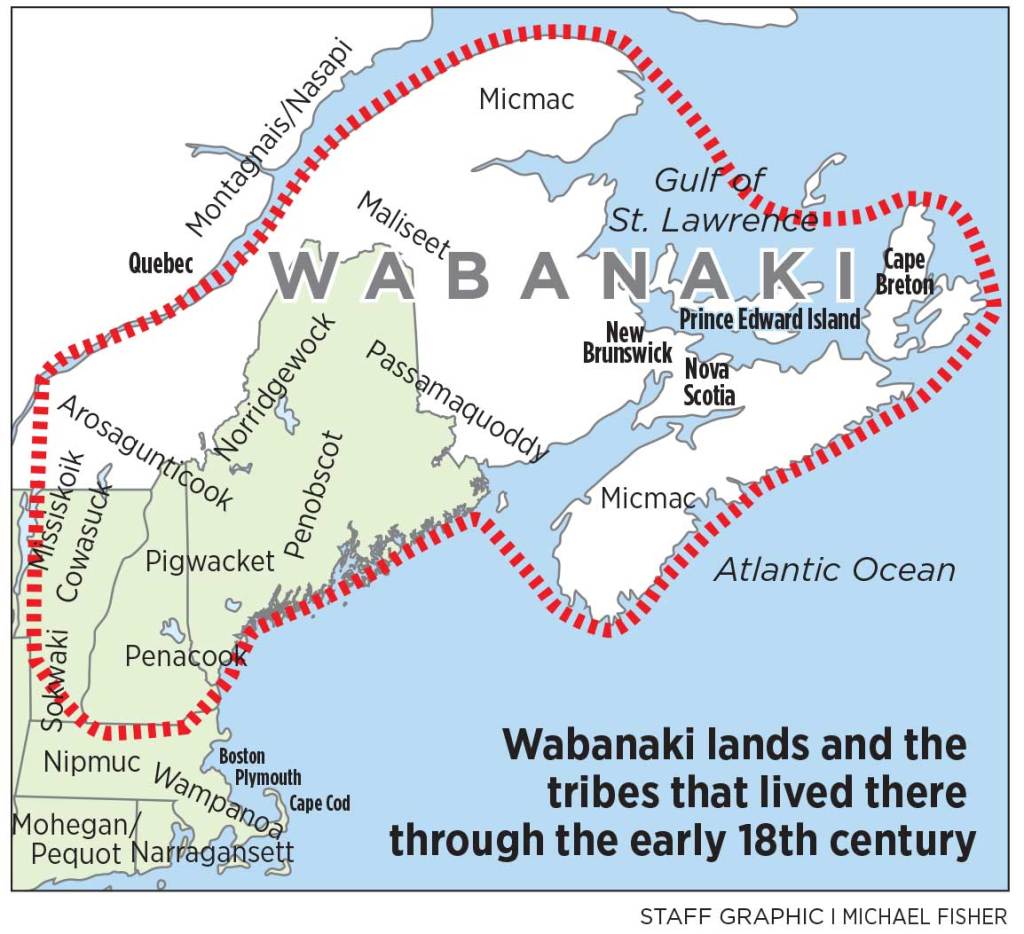

The Indians, a team of long-distance Micmac traders, spoke a broken European language – possibly Basque – and “came boldly aboard.” They understood some English, drew a map of the coast for the visitors with a piece of chalk and mentioned their knowledge of Newfoundland, hundreds of miles by sea to the northeast. They spoke of their encounters with Basque fishermen and “much desired” the English stay to trade.

It was no isolated incident. Historians familiar with such firsthand accounts of the early contacts between Europeans and our region’s original inhabitants have long been aware of how much more the Indians knew about Europe than Europeans knew about them – and how they used their knowledge to dominate the seas. Accounts of Micmacs sailing European vessels are as common as the presence of European copper and iron implements in New England Indians’ villages. At least one Micmac leader, Messamouet, had been to France, where he was a houseguest of the mayor of Bayonne – meaning his people had discovered Europe before the English had ever seen the Gulf of Maine.

Maine’s Wabanaki tribes also used this knowledge to trade on the seas and to protect their maritime territories, both in the early contact period and the colonial era that followed, keeping Europeans on their toes and, for many decades, out of Wabanaki territory. Outside of academia, however, few know much about this intriguing aspect of colonial Maine history, which is especially relevant today, as the Passamaquoddy and Penobscots clash with the state over saltwater fishing rights the tribes say they never relinquished.

This fall, a new scholarly paper in the “Journal of American History” put the Wabanaki’s maritime past back in the spotlight, provocatively arguing that Maine’s native people didn’t merely sail the seas, they were engaged in a geopolitical struggle to block England’s efforts to create an trans-Atlantic mercantile empire.

“It was a threat to jeopardize Britain’s campaign for colonial ascendency in the 18th century,” says the paper’s author, Matthew R. Bahar, an assistant professor of history at Oberlin College in Ohio. “The inability of Britain to muster resources to deal with this problem allows the Wabanaki to advance their own agenda in the northwest Atlantic.”

This campaign, as Bahar tells it, was a long one, taking place across nearly a century of Anglo-Wabanaki wars, from King Phillip’s War (which started in 1675) to the end of what Americans call the French and Indian War (which ended in 1763.) The Indians, he argues, became feared for their “incessant devastation of the North Atlantic fishery, their serial impressment of British seamen, their commandeering of British sailing vessels, and their destructive naval warfare.” They preyed on the “soft underbelly of the British imperial economy” to siphon off vessels, captives, and cargoes.

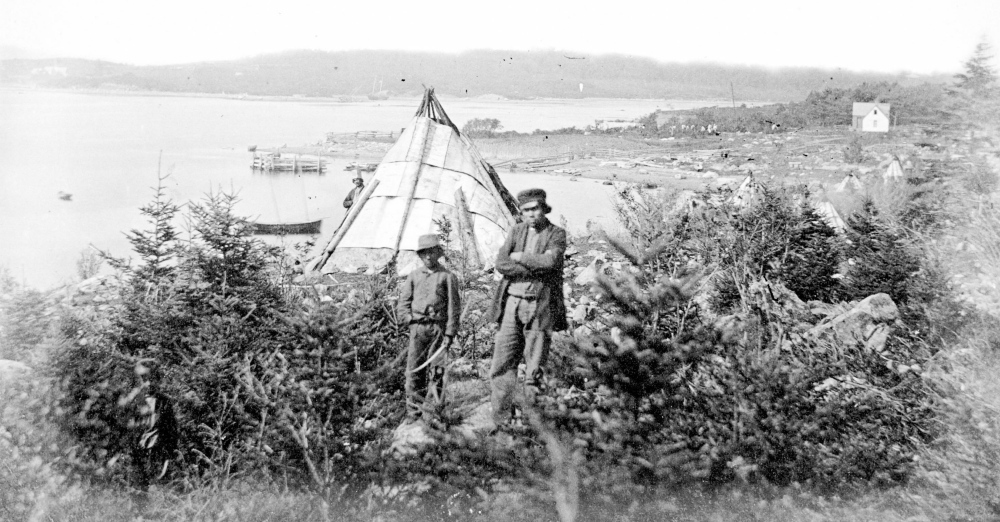

That the Wabanaki were a seagoing people is beyond dispute. Archaeological evidence collected by Maine’s Bruce Borque and others shows Wababanki were hunting seals, porpoises and baleen whales centuries before European contact. Their mythic hero Gluskap came from the sea, imparted his knowledge to the people and returned to the sea in his stone canoe prior to the arrival of Europeans.

By the time the English reached New England, French and Basque explorers and fishermen had been visiting the waters off Newfoundland and what is now eastern Quebec and New Brunswick for more than a century. Montagnais and Micmacs traded furs for European goods, which passed through centuries-old Indian trading networks that extended from the Inuit of Greenland to southern New England and beyond. European goods and technology reached Maine’s Indians long before the people who made them, which is how a 12th-century Norse coin (presumably from the abortive Greenland Norse settlements) was found at a pre-contact Wabanaki site at Naskeag, Maine, and how the Sacos could be wearing brass breast plates to their first encounters with English explorers in 1603.

European vessels – either traded for or stolen from the French and Basques in the Gulf of St. Lawrence region – supplemented the birch-bark canoes the Wabanaki had long used to access fish, seals and birds on the islands and bays of the Gulf of Maine. When Henry Hudson rowed ashore in upper Penobscot Bay to mend sails in 1609, they spotted local Indians bearing down on them with “two French shallops” who insisted they engage in trade. In the 1650s and 1660s French Jesuits marveled at the Indians’ skills with such vessels, noting “they handle them as skillfully as our most courageous and active sailors of France,” using them for “crossing vast seas without compass, and often without sight of the Sun, trusting to instinct for their guidance.”

“They started early on with shallops, which were kind of the training wheels for Indians wanting to use European sailing vessels,” says Bahar, who is at work on a book on his recent paper’s themes. “Once they became proficient with these, they moved up to fishing sloops and ketches and schooners, but that seems to have been the end of the upgrading.”

During the Anglo-Indian conflicts – most of which were embedded in wider Anglo-French wars – Wabanaki regularly hijacked such vessels in the Gulf of Maine, sometimes using them to lay siege to English fortifications in places like Scarborough or Pemaquid. Some twenty fishing ketches were captured during King Phillip’s War, and at one point during King William’s War (1688-1697) an Indian-held schooner and ketch fired cannon at a fishing vessel in York Harbor to force it to surrender. Fifteen or 16 more fishing vessels were taken by the Penobscots at the opening of Dummer’s War in 1724, including two schooners they used for seal hunting at Grand Manan.

They often forced the crews to help them hail unsuspecting English vessels, to navigate vessels into unfamiliar harbors, or simply to work as their servants. Vessels were often sold at the French fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island.

After the outbreak of the Golden Age of Piracy – the era when Blackbeard terrorized the seas and Sam Bellamy’s men raided the Maine coast – British officials began referring to the Indians as “pirates.” In 1726, three were hung for piracy in Boston after an unsuccessful attempt to hijack a vessel near Nova Scotia.

Bahar frames all of these activities as having been part of the Indians’ effort to undermine the British mercantile system and create what he calls a “Wabanaki Atlantic,” which many scholars of the period will find a bit of a stretch. His assertion that the Wabanakis “blue-water campaign” presented a threat to the British empire is hyperbolic: their targets were fishing and coastwise trading vessels of 10 to 30 tons, not the 100- and 200-ton ocean-going brigantines and ships that were the lifeblood of the transatlantic economy, or the 250- and 300-ton frigates assigned to protect the commerce of empire. The attacks took place almost exclusively in harbors or inshore waters, not in the oceanic shipping lanes or on the offshore banks where the imperially significant fishing activity took place.

“This wasn’t a desire to control the oceans, it was maritime guerrilla activity,” says one of the leading authorities on the colonial and pre-contact Wabanaki, Harald Prins, an anthropologist at the Kansas State University, who is finishing a book on the Wabanaki’s maritime heritage. “The Wabanaki knew if they were pushed away from the coast they would have a hard time surviving, so they were doing this to resist the loss of their access to the sea.”

Prins, who has been long familiar with all of the accounts in Bahar’s paper, says Maine’s Indians took small European vessels for specific purposes, but already had a superior technology for simultaneously exploiting the Gulf of Maine and its vast interior watersheds: the birch-bark canoe. “You could go over the narrows from Frenchman’s Bay to the Union River and then on through Green Lake to Old Town,” Prins notes. “There’s a whole parallel network of rivers and lakes and portages behind the coastal line that allowed them to go in the same canoe from Monhegan to Old Town, and no whale boat or shallop could ever follow you.”

European vessels just weren’t an improvement on the technologies the Indians had already developed to live in our island-studded, river-and-lake-pocked part of the world. “These are very specific adaptations for their environment, like the Apache with their mustangs or the Tuareg (of North Africa) with their camels,” Prins says. “The canoe is a fantastic vehicle for taking around a waterfall or over a sandbar and it lent itself to the hit-and-run tactics you see the Wabanaki use in their conflicts with the English.”

They were, in short, trying to safeguard their homeland, Prins says. When they lost the bays of molting ducks, the clam flats, the fishing grounds and sealing and birding islands, they lost a huge part of their resource base. They continued to use these resources as best they could long after most of their coastal lands were lost – and still do today – but they were diminished.

Bahar agrees that the Wabanaki were seeking to maintain control of their near-shore territories and resources, but maintains they had wider strategic ambitions. “Indians were contesting the British efforts to integrate the Atlantic into a seamless economy,” he says. “They weren’t trying to go toe-to-toe with the Royal Navy, but by targeting the fishery, they were taking on a cornerstone of the British Atlantic trade and economy.”

Bahar’s paper, “People of the Dawn, People of the Door: Indian Pirates and the Violent Theft of the Atlantic World,” appears in the September 2014 issue of the Journal of American History. Prins’ book appears next year.

Send questions/comments to the editors.