Back in the 1970s, those of us eating natural, organic and vegetarian food in Maine didn’t have a lot of options. Grow your own. Find a local farmer selling market vegetables. Or head to a cramped, lightly stocked and patchouli-scented co-op to buy wheat germ and raw goat’s milk from hippies in bandanas and oversized glasses.

These days, when shopping on Somerset Street at the gleaming merchandising marvel that is the Whole Foods Market, I wonder how we got from those quirky, disco-era health food stores to this grocery extravaganza known for enticing whole paychecks from pockets.

When did health nuts morph into soccer moms? Why did kale go mainstream? How did “vegan” become an everyday word?

Author Joe Dobrow says the spark that ignited this natural foods revolution came on Feb. 26, 1989.

That’s when the CBS news program “60 Minutes” aired a controversial segment called “A Is for Apple.” The report opened with Ed Bradley saying a pesticide called Alar was “the most potent cancer-causing agent in our food supply” and that children consuming apples and apple juice were at risk of one day developing cancer. The piece went on to document how the U.S. government knew about the risk but had done nothing to contain it.

A lawsuit by apple growers and a massive industry-funded public relations campaign followed, but the damage was done.

“When ’60 Minutes’ did the report, that was the killer moment,” said Dobrow, author of “Natural Prophets: From Health Foods to Whole Foods – How the Pioneers of the Industry Changed the Way We Eat and Reshaped American Business,” which was published in February.

“That was really the first time mainstream America woke up and became concerned about the food system and whether big government had the consumer’s interest at heart,” Dobrow told me by phone from his home in Arizona. “This shifted a lot of consumers into natural food stores.”

Dobrow is the former top marketing executive for the nation’s largest natural food retailers, including Whole Foods, Fresh Fields and Sprouts, so he has had a front-row seat during the transformation of health food from a movement into an industry.

His book offers a captivating behind-the-scenes look at exactly how we got from the dusty co-ops of yesteryear to the shiny mega-stores of today. It also explains how the growth of natural foods propelled a number of health food products into the mainstream, such as granola bars, almond milk and kale. Along the way, Dobrow explains how natural foods companies (built on values and ideals as much as capitalist principles) have begun to influence mainstream business culture by promoting concepts such as corporate accountability, transparency and the triple bottom line.

Dobrow grew up outside of Boston and, as a child, loved going to the supermarket with his mother.

“I stopped eating red meat when I was 13 and shifted to an all natural foods diet not long after that,” Dobrow told me. Supermarket shopping became more difficult after that.

Fortunately, Dobrow was living in one of the country’s hotbeds of organic foods.

In the book, he writes, “New England became a vital center for the natural foods industry, second only to Boulder, whose aura, timing, talent, and Rocky Mountain holy water had made it the industry’s true cradle of development.”

Dobrow states that an interest in natural foods comes, well, naturally to New Englanders, who have long emphasized education and exhibited “reformist principles” and “tendencies toward rebellion and self-sufficiency.”

Some of the New England-based industry pioneers Dobrow writes about include Gary Hirshberg, Helen and Scott Nearing, Michio and Aveline Kushi, Paul Keene and Sylvester Graham.

Maine makes a few cameos in the book. Dobrow writes about the homegrown Fresh Samantha juice brand that was ultimately swallowed up by Odwalla and then Coca-Cola. We learn that Richie (“an avid vegetarian”) and Julie Gerber were back-to-the-landers in Maine before heading to South Florida in the early 1980s to buy and expand the Bread of Life chain of health food stores. Although not a food brand, Tom’s of Maine is mentioned numerous times.

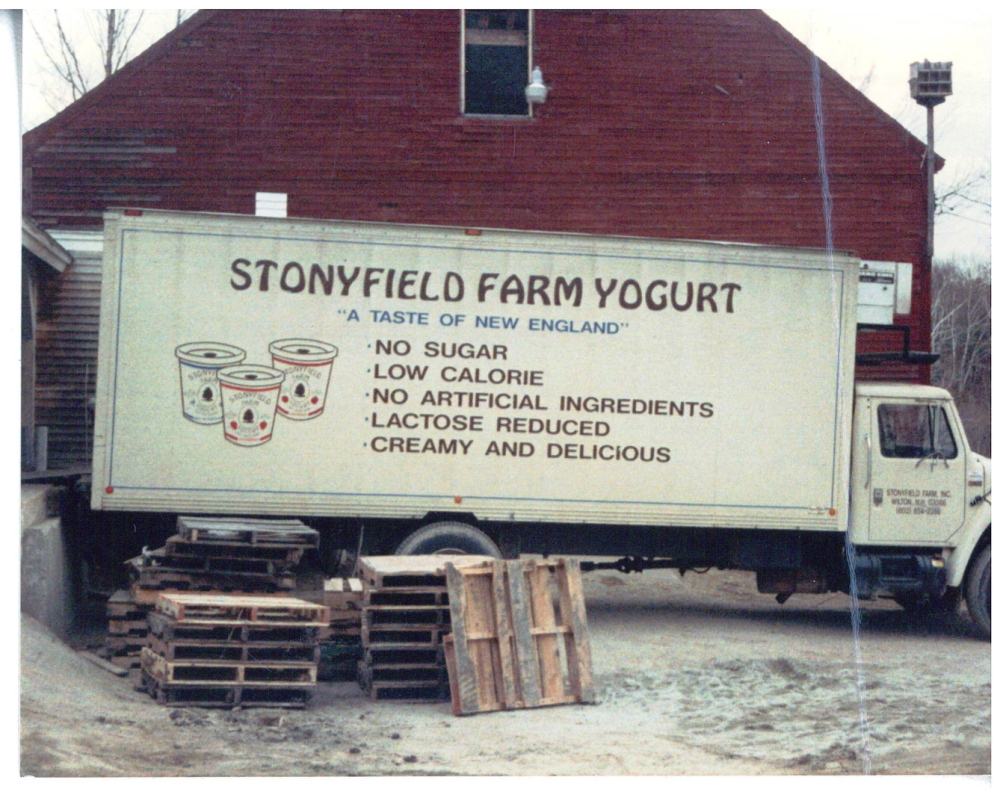

Dobrow also explores the development of some of the industry’s best-known brands, many of which make vegetarian foods, such as Stonyfield Farm, Eden Foods, Celestial Seasonings and Cascadian Farm.

“Certainly vegetarianism, veganism, the raw food movement and the local food movement are all subsets of the natural foods movement that have fueled its growth,” Dobrow said, when I asked him about the historical connections between health food and vegetarian food.

Near the close of the book, Dobrow writes, “Venture capitalists poured $350 million into food projects in 2012, mostly natural, organic, and/or vegan.” He credits the growing number of vegetarian-oriented fast food restaurants, such as Veggie Grill and Native Foods, with exposing more people, particularly investors, to the taste and potential of plant-based food.

Noting that we’ve seen an increase in “shelf-labeling of vegan and vegetarian foods” in this country, Dobrow told me it’s not surprising that a recent wave of vegan-only grocery store openings is taking place outside the United States, including Veganz across Germany and iVegan in Taipei and Rome.

“Although we in the U.S. like to think of ourselves as being on the cutting edge, when you look globally you realize that’s not the case,” he said, citing the much stricter food labeling laws in other countries.

Might vegetarian foods follow the path taken by natural foods and ultimately become mainstream? Dobrow said an outside spark, such as a massive meat recall or a particularly damaging report, could push meat off more plates. In the meantime, he says, we should keep an eye on how much shelf space conventional grocery stores dedicate to vegetarian foods. Dobrow noted how traditional supermarkets initially shied away from health food, but “in the past five years or so, they’ve gone into it wholeheartedly.”

“If (vegetarianism) is really a movement that’s going to expand,” Dobrow said, “we’re going to see it reflected on the shelves of the conventional food stores.”

Avery Yale Kamila is a freelance food writer who is lives in Portland. She can be reached at:

avery.kamila@gmail.com

Twitter: AveryYaleKamila

Send questions/comments to the editors.