Writers, photographers, painters, journalists and actuaries were still breathing smoke and effluvia from the two-day Great Fire of 1866 when they began to document its rampage through Portland on July 4 and the changes it made upon the city.

As long as the community remains, people will continue to study the event that left some 1,500 buildings in ash, 10,000 homeless and somewhere between $12 million and $25 million lost. Because the fire began during the day on a holiday, only three lives were lost. Still, it is always noted with a measure of chagrin and amazement that Portland’s urban conflagration was the worst in the nation, before Chicago burned and later horrors arrived.

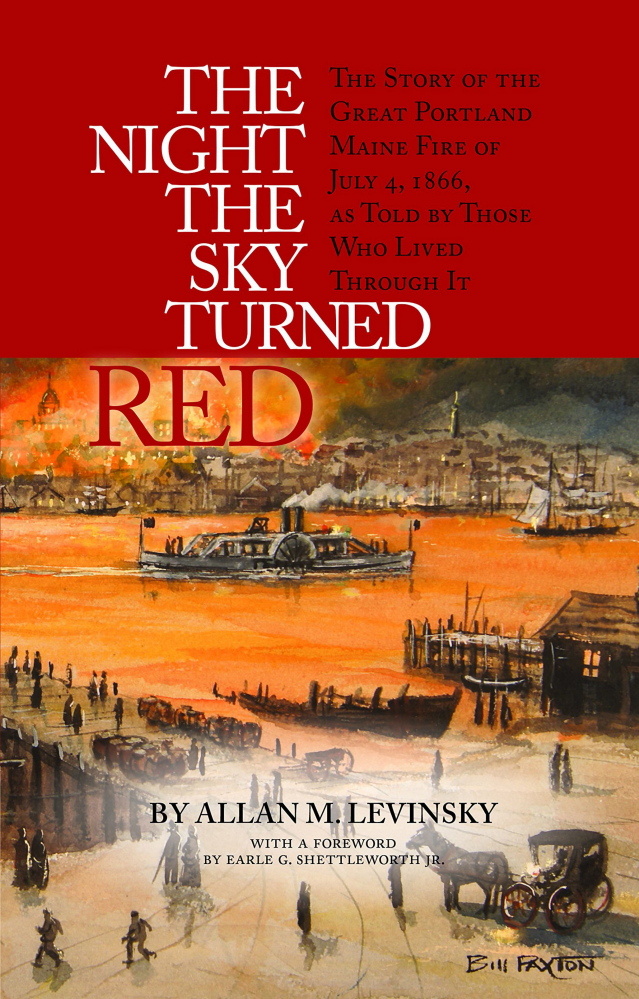

Allan M. Levinsky’s well-organized, fast-paced book “The Night the Sky Turned Red” is, as State Historian Earle G. Shettleworth states, “a valuable addition to nearly a century and a half of literature” about the event. A Portland native, Levinsky knows his way around the peninsula’s streets, past and present.

He has done his homework, drawing on eye-witness reports such as those of newsboy Cyrus H.K. Curtis, journalist and novelist John Neal, Mayor Augustus H.K. Stevens and Anne Longfellow Pierce, a Congress Street resident and sister of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Photographs from the Maine Historic Preservation Commission show the stark reality of a city truly destroyed.

Levinsky’s short, accurate publication follows on the heels of a 2010 book, “Portland’s Greatest Conflagration” by firefighter Michael Daicy and Don Whitney. That excellent effort was written from the fireman’s point of view, examining water sources, equipment, manpower and attempts to control the blaze in strange weather conditions. The two books complement each other, providing pieces of an extremely complicated story that may never truly be known.

Levinsky’s use of Neal’s reporting reminded me of the skill of that novelist, attorney and national observer. Most of Neal’s biographers, all literary men, have consigned his “Account of the Great Conflagration” to “hack work,” when indeed it is the very best of modern journalism – accurate, fair, compelling and still mined for facts. Superior to most of his novels in style and substance, parts of Neal’s account appear in Levinsky’s appendices.

I previously knew of only two deaths from the fire. In his book on the Eastern Cemetery, Professor William B. Jordan included the discovery of another body nearly two and a half decades later. Levinsky brings it into the fire record. This is how history builds on itself.

Still, in checking the bibliographies and conclusions of “The Night the Sky Turned Red” and “Portland’s Greatest Conflagration,” I think there might be more to do.

While Daicy and Whitney alluded to the crisis caused in the insurance industry, neither seems to recognize Alden L. Todd’s classic, “A Spark Lighted in Portland” (1966), which demonstrates how the fire changed the American underwriting industry immediately. Perhaps now is the time to look more deeply at how Portland adapted or failed to adapt.

Historian Levinsky ends on an upbeat note. In an article marking the 100th anniversary of the fire, he writes, the Portland Press Herald “noted regarding the rebuilding of the city, many felt it had advanced at least fifty years, because of the opportunity for rebuilding on a larger and in a better style.”

Others would suggest differently, and the truth lies somewhere in local and national economic statistics, structures and, of course, one’s perspective.

William David Barry is a Portland historian who has authored or co-authored books including “Maine: The Wilder Half of New England” and “Deering: A Social and Architectural History.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.