Sometimes when we watch a film, our experience of thinking about the movie surpasses our experience of watching the movie. With novels, we often do this whenever we put down the book. And the idea of chapters in a work of fiction seems not only to encourage this, but to derive from it.

Live performance, on the other hand, is dedicated to keeping you inside the experience of the performance, with suspension of disbelief intact. (Have you ever gotten up to go to the bathroom during a theatrical performance?)

Visual art, however, generally unfolds at the viewers’ pace. Sometimes it is meant to provide a context for conversation. Other times, visual art rather insistently tries to put you in your place.

The 2014 Maine College of Art faculty show “South of No North” covers the topic of the viewer’s physical relationship to the work with such unusual grace and clarity that even very casual viewers should come away with startling insights about what it means to experience contemporary art.

The easiest work to appreciate is Bennett Morris’ backlit post-apocalyptic scene placed (essentially alone) in the Institute of Contemporary Art’s handsome middle gallery. The piece features six router-cut rectangular Lucite sheets standing on a pedestal lit by a projection through the uncut, translucent rear sheet. To see the piece as a landscape, you look straight through the series of sheets: Each is cut so that it maintains the rectangular outer form (like a frame) and the effect is like a layered stage set. The whole thing has a weird Wizard of Oz feel to it, as though the grumpy apple tree forest was replaced by waves of soaring towers of futuristic battleships long ago crumpled at the losing end of a war.

To stand directly in front of the work is to experience a masterful multimedia painting. The details and rendering are exquisite, and within the projected pink glow are downward floating white flecks that impart the soft silence of falling snow – until you think about it. Is that snow, or fallout? And when you decide it is fallout, where does that leave you?

The glow flows straight through the router-rendered scene of techno pines to reflect onto the wall behind the apparatus. You can’t help but move around the piece to check it out – and you don’t need Toto to pull back the curtain. The scale and shape of the work in the space pull you in. We see the sheets set at logarithmic distances (the farther from the light source, the more distanced they are – like the planets from the sun), and we wonder if that’s the old theatrical standard. The colors of the standing sheets are similarly graded, moving from clear to white to what looks like 10 percent gray then 20 percent then 40 percent.

What is interesting about the piece is that there is a single point from which it is best viewed as a complete and compelling fiction. But to see its function and fabrication, the viewer must (and can) move all around the piece, its base and so on. This becomes clear to any viewer, particularly if others are present and you need to wait to occupy that ideal single-point perspective.

Taking this model to the rest of the exhibition is quite easy and satisfying.

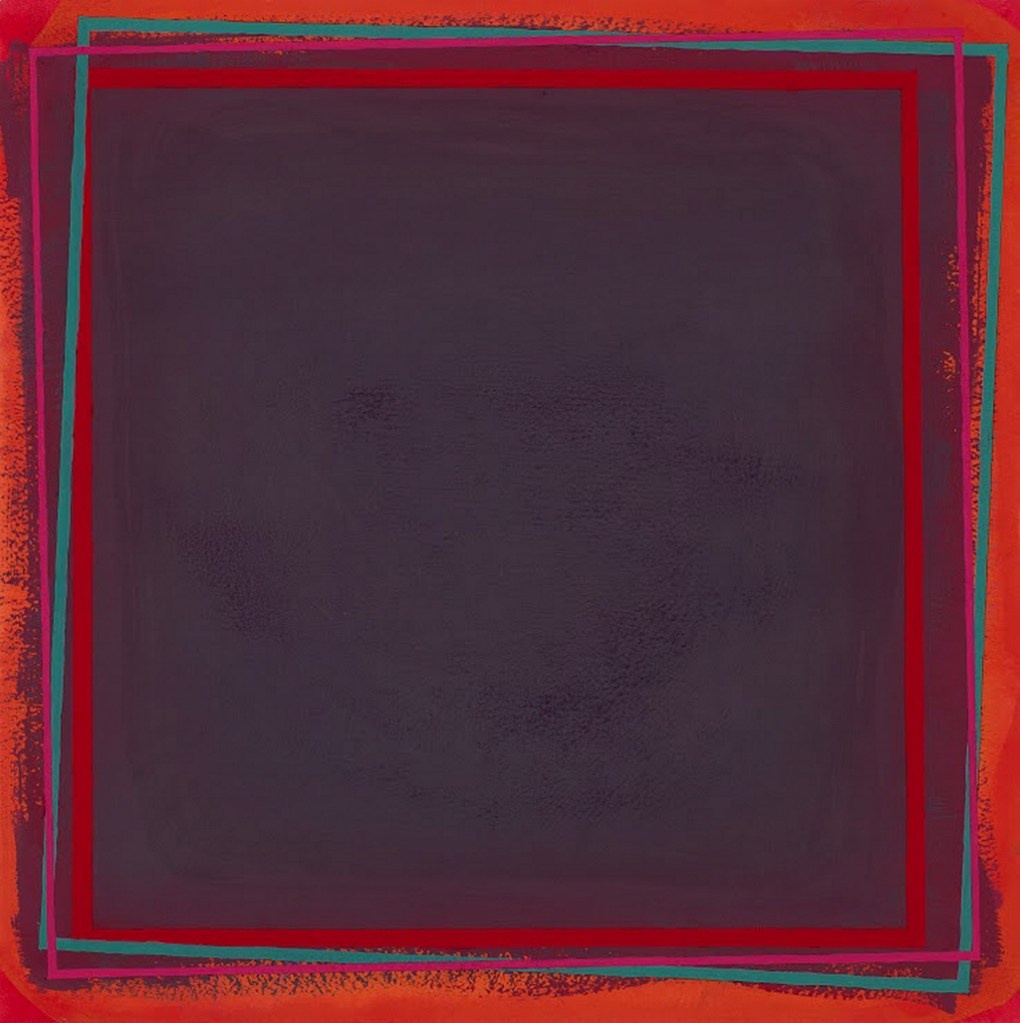

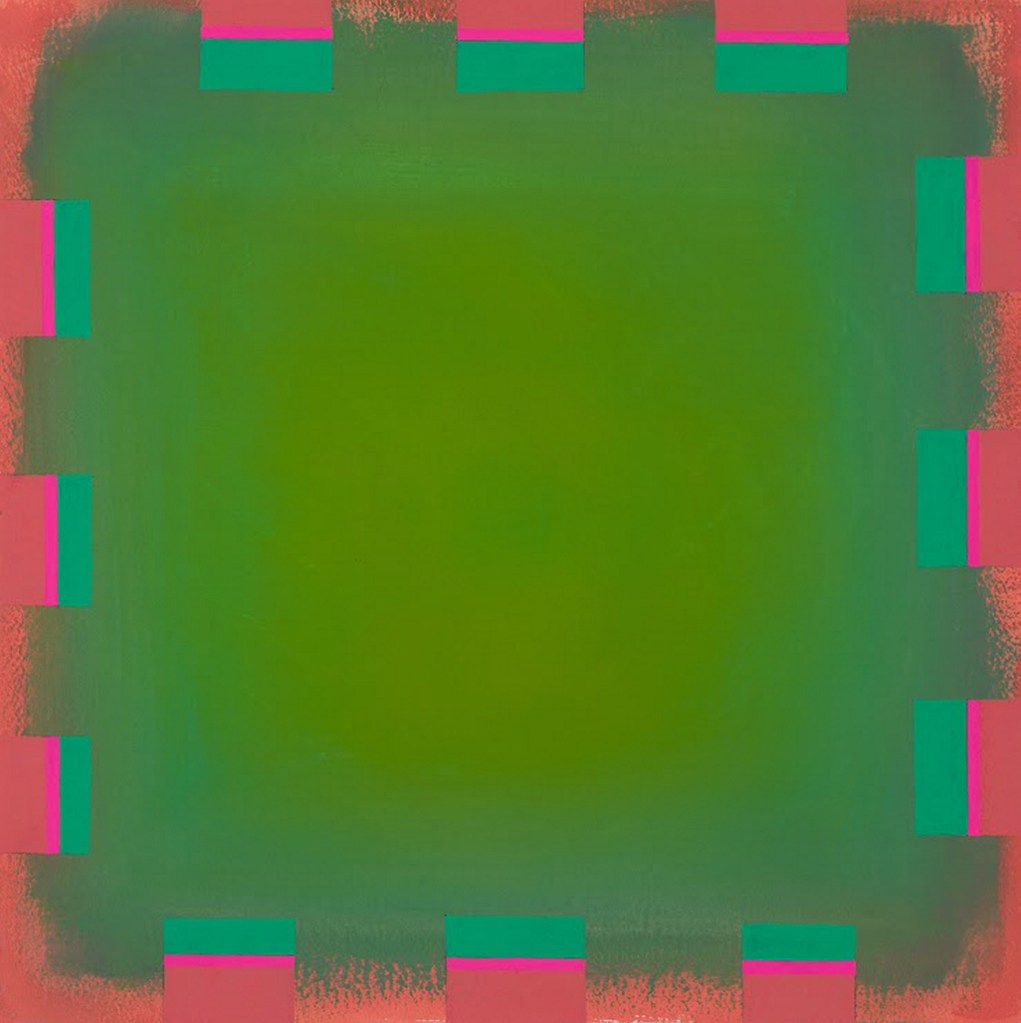

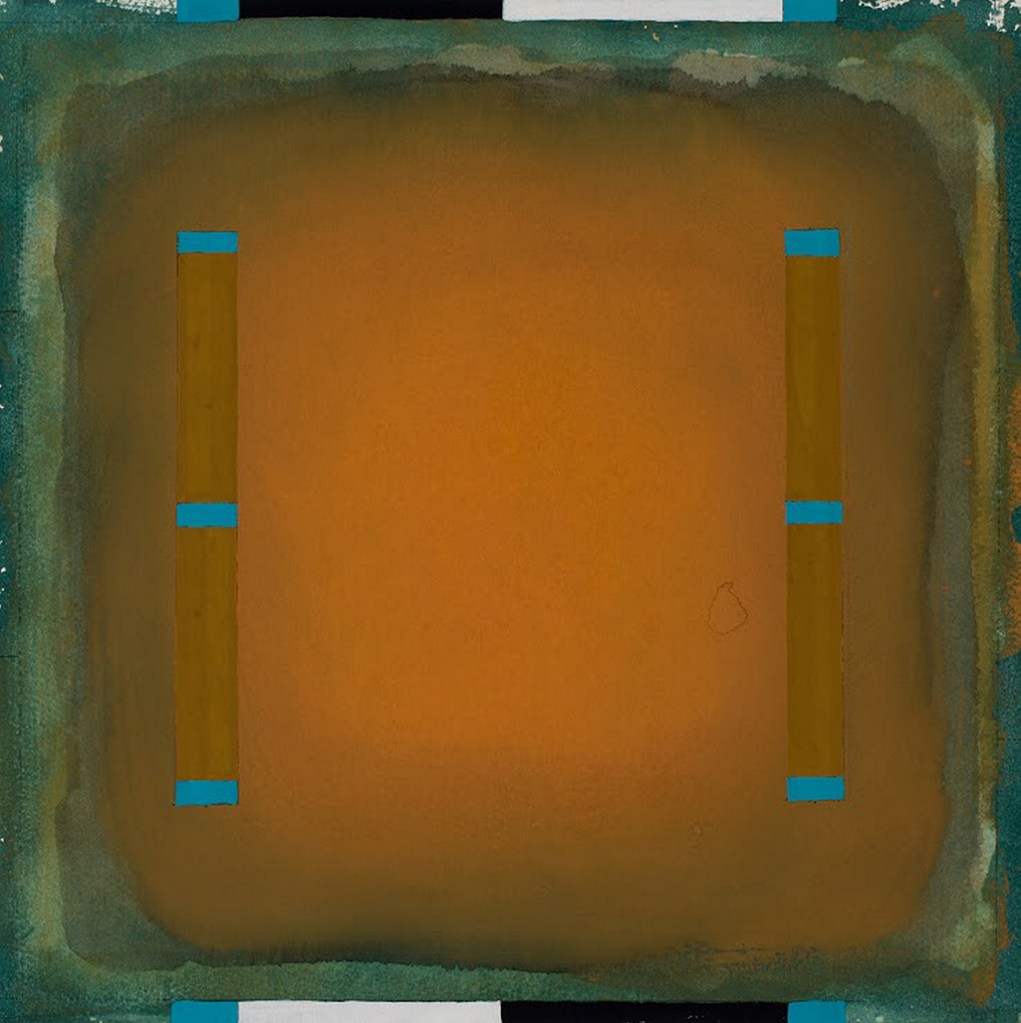

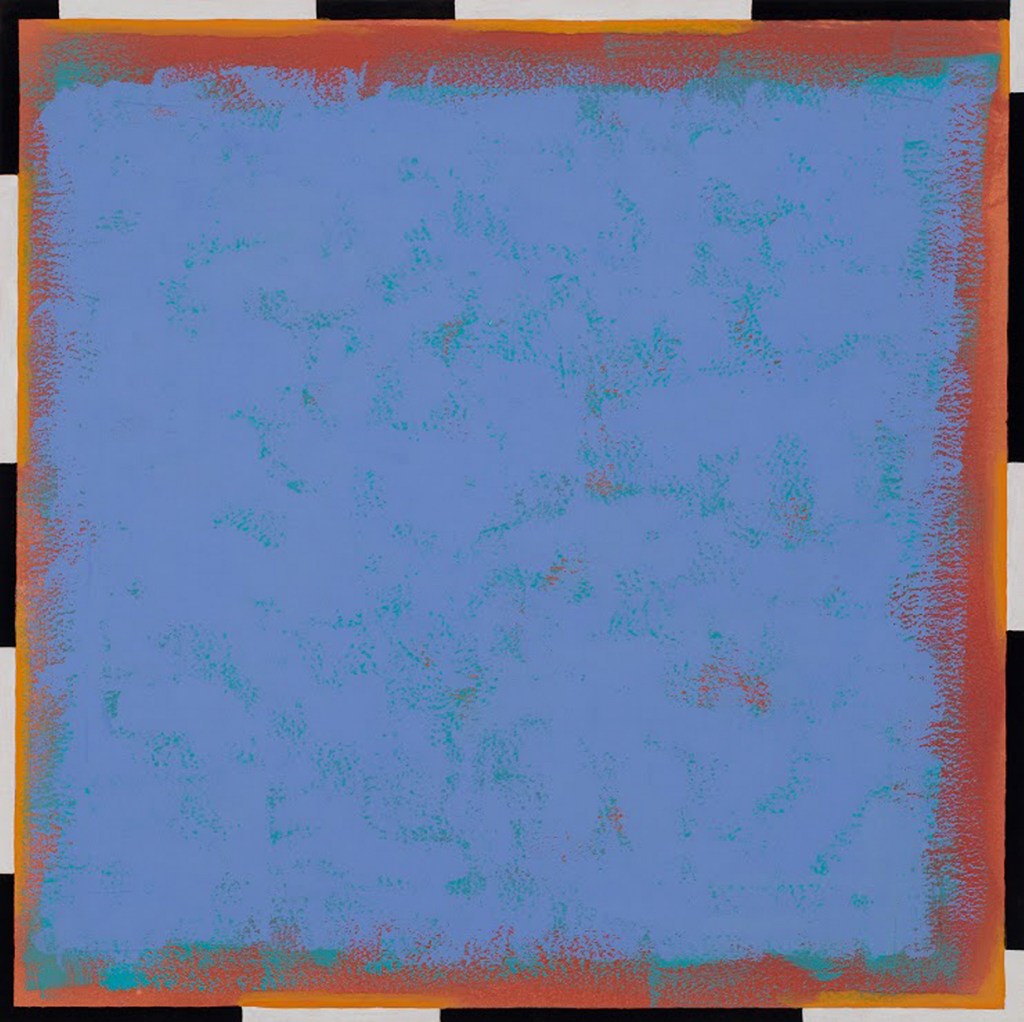

Honour Mack’s work, for example, takes a tack from viewer-oriented art such as mandelas and modernism. Her series, “Hermetic Charts,” “Determining Center” and “Color as a volume and a substance: Illuminations,” reveals her broad interest in the relationship between the viewer’s body and the image. Her historical references to Hindu, Buddhist and American art (most obviously, the centered circle paintings of Kenneth Noland) make it clear she thinks this perceptual experience is a kernel of the human condition rather than an ephemeral fiction conjured by our culture.

In other words, Mack’s work is all about the idea of that fixed viewing point. And like a good Modernist, Mack investigates this spiritually and seriously.

Sean Glover’s two installation works are directly about visual perspective. One features a reflecting telescope mounted inside a Buckminster Fuller-inspired geodesic jungle gym. Its frame is literally a cage denying the physical place one would have to be in order to use the single-point perspective lens.

The other work, “Let’s not think about tomorrow,” features fresco-covered foam detritus on the floor, over which floats a giant helium balloon inside a geodesic balsa frame. This piece metaphorically contrasts the disorganized proliferation of human culture (the detritus becomes a model of a city with the fresco giving it an old-school cast) over which floats the specter of an organized (but poppable) visionary future. Again, it’s a debate between the conceptual chaos of culture and the elegance of a singular perspective.

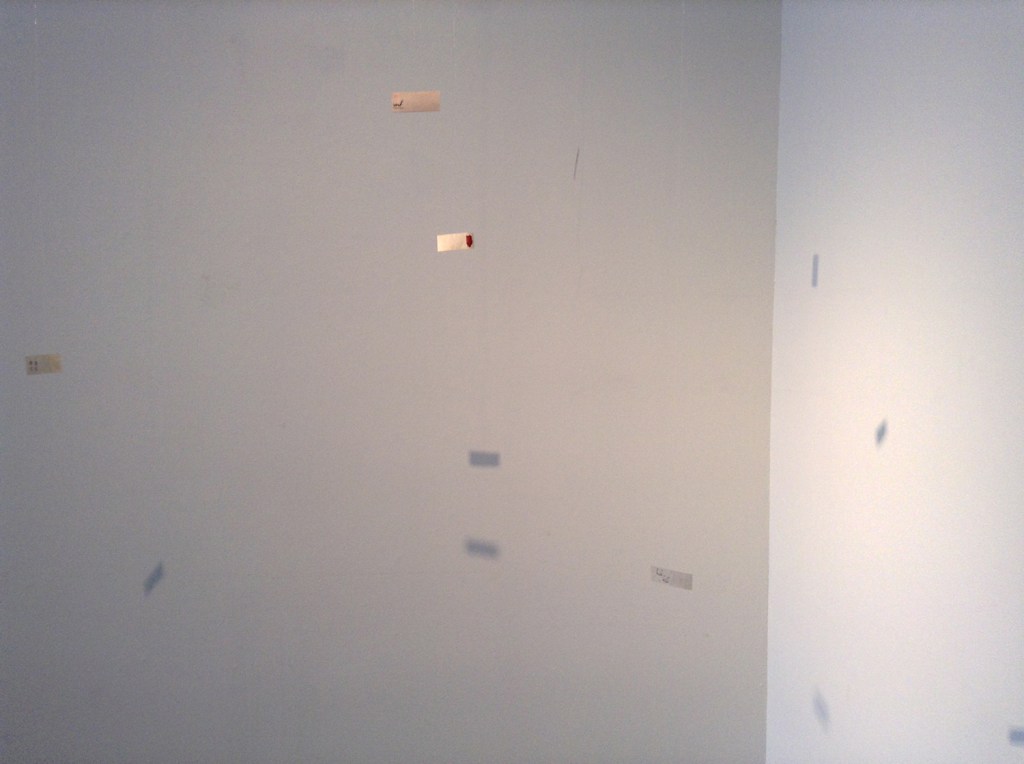

Chris Stiegler’s “Sebastian Black/Elements of Style” (a work by artist Sebastian Black that Stiegler curated into the show) explodes the idea of single-point perspective by suspending (from monofilament) five tiny images culled from magazines that swirl in the air. The accompanying text is erased but floating (visually) among the images’ shadows on the wall, to create a destabilized and decentralized work. The piece not only lacks direct authorship but stable location. The other half of the piece is off site at the curator’s apartment – a fact Stiegler explains in a printed essay (if you can’t work through the excruciating first half, jump to the discussion of Black’s piece) that finishes with the explanation that the divided quality of the work is “meant as a direction toward contemplation.”

In other words, Stiegler means to get you – and leave you – outside of the work.

Oddly enough, this brings us to a cultural practice widely considered anathema to contemporary art but tacitly advocated by Morris’ set installation – connoisseurship. The connoisseur, after all, is not taken in by the overall fiction of the work, but considers an art object in terms of its physical condition, how it was made and by whom. These days, the art world would have us associate connoisseurship with auction houses and the physical handling of art (i.e., market expertise), as opposed to the specializing in stylistic issues, such as identifying the artist who made a specific painting.

This unusual pro-connoisseurship position also supports the powerful (and likely unintentional) argument of “South of No North” that contemporary art functions on a cultural foundation provided by painting: the physical experience of perspective.

At the core of “South of No North” is the idea that you can’t unsee the unveiling of illusion, like how a movie special effect is made or how a magic trick is done. The work here bobs between wanting you to experience it directly without questioning it and wanting to show off how it does the trick, which means getting outside of the piece and thinking about how it functions (sort of like reading the recipe rather than tasting the food). But then, this could all be described as the essential distinction between Modernism and Post-Modernism.

In the end, “South of No North” comes across as an enjoyable and brilliantly curated show about perspective, suspension of disbelief and the broken balance between being able to experience something as an intended fiction into which we can (and should) immerse ourselves and its cynical other side, that being transported by a fiction is uncool.

Most impressive is that “South of No North” avoids any preachy polemic: Some viewers will prefer only seeing Morris’s piece from the prescribed pictorial position, while others will be more fascinated by its technical craft, best seen by walking around it. It’s all a question of whether you want to be awakened from the dream. But, once he tells you to, you can’t ignore the man behind that curtain.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

danykany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.