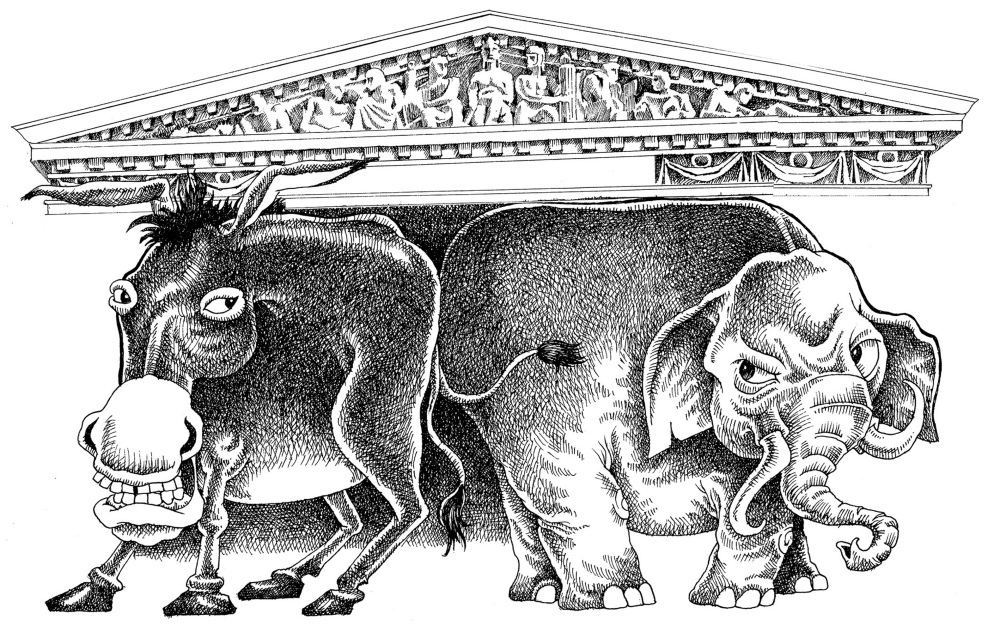

Mr. Dooley, the Stephen Colbert of the late 19th century, taught us that the U.S. Supreme Court follows the election returns. But does that include midterms, too?

If today’s justices are any indication, the answer is no. None of the current justices older than 75 – and there are four of them – has shown any willingness to retire.

The old Republican appointees, Antonin Scalia (born 1936) and Anthony Kennedy (ditto), will take their chances and wait for a Republican president. The old Democratic appointees, Ruth Bader Ginsburg (born 1933) and Stephen Breyer (born 1938), have apparently decided that Hillary Clinton is sure to be elected president or that they don’t care who replaces them.

Given that a Republican Senate doesn’t seem to trouble them, is there any scenario in which either Ginsburg or Breyer will retire voluntarily before President Obama’s second term is up?

Reading the tea leaves, the answer seems to be that these justices will get nervous only if Clinton decided not to run (say, for health reasons) or started to poll substantially behind some credible Republican candidate (say, Jeb Bush).

If the justices believe that the midterm elections represent a fundamental repudiation of the Democratic Party that substantially increased the likelihood of a Republican president being elected in 2016, that might well make them think of early retirement. But that’s unlikely to be their interpretation of the elections. Instead, they will most probably assume – alongside most pundits – that the American people are very comfortable with divided government, and could give us a Democratic president and Republican Congress well into the future.

The justices’ subjective understanding aside, that still leaves the question of how the midterm elections will affect the Supreme Court as an institution. Here, the story is different. With four justices officially old (OK, unofficially), we need to contemplate the very real possibility that one or more of them might have to retire in the next two years for reasons of health. What will a Republican Senate mean for potential Obama nominees to the Supreme Court?

The last four justices – John Roberts, Samuel Alito, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan – were all appointed at moments when the president came from the same party that controlled the Senate. All four were identifiably party loyalists, three with politicized executive branch experience. All four could talk the talk of centrism, but with the possible exception of Roberts, who genuinely convinced some Democrats of his possible moderation, all were expected to vote the way other party loyalists wanted. None of these justices was a crossover candidate – because none had to be.

That isn’t to say that these four justices are radicals. In all cases, a minority filibuster was in theory possible, and it demanded some gesture in the direction of moderation. And it’s worth remembering that, when the Democrats instituted the so-called nuclear option and eliminated the filibuster for ordinary judicial candidates, they left untouched the possibility of filibustering a Supreme Court nominee. So even if the Senate had stayed under Democratic control, Obama would have had some incentive not to nominate radical left candidates.

But in practice, it’s difficult to imagine the minority party actively filibustering a presidential nominee to the Supreme Court with the whole world watching. It hasn’t happened since 1968, when Republicans filibustered Lyndon Johnson’s crony Abe Fortas, who had been nominated for chief justice. That means Obama would have been in a much stronger position to nominate a liberal if he had a Democratic Senate than he will be facing down Republicans.

All this means that a Democratic nominee for the Supreme Court in the next two years will probably need to have a strikingly different ideological profile than any of the last four nominees. To be confirmed by a Republican Senate, the nominee will have to be at least a credible centrist – more in the model of Sandra Day O’Connor or Kennedy than Ginsburg or Breyer.

What potential candidates fit that description? The big midterm election winners in the pool of potential justices are people like Merrick Garland, chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia circuit, or Sri Srinivasan, a relatively recent appointment to the D.C. Circuit.

Garland, a former federal prosecutor, worked for the Department of Justice during Bill Clinton’s administration – but in the criminal division and then as principal associate deputy attorney general (yes, that’s a real title), where he supervised big-ticket criminal investigations such as the Unabomber search.

(I first met him in the Department of Justice, when, as a summer intern, I was the only person left in the building on a Friday afternoon in the dead of summer and someone had to write a memo on whether the government could use the Army to look for a missing duffel bag in the desert somewhere outside Kingman, Arizona.)

Garland is known as a moderate, and he could plausibly replace any of the three old white men should one of them have to step down. As a judge he has managed not to incur the wrath of conservatives, and he is probably confirmable.

Srinivasan has much less experience, having been appointed to the federal bench in 2013. But Srinivasan has even less partisan baggage than Garland. He never held a political appointment until 2011, when he became principal deputy solicitor general. Before that he had been a lawyer in private practice and a well–respected assistant in the solicitor general’s office during the George W. Bush years. The Senate confirmed him for the D.C. Circuit by a vote of 97-0 – something very close to a certificate of confirmability.

Srinivasan has another advantage that might be useful to Obama. Because he would be the first South Asian or Asian justice, it might be possible to nominate him even to fill the seat held by Ginsburg.

Of course, there would be substantial pressure for the feminist giant to be succeeded by a woman. But Obama has already nominated two women to the Supreme Court. A Republican Senate – and the need to find a confirmable nominee – might give him cover to name a man from a previously unrepresented minority group. One Democrat, at least, has reason to be smiling.

— The Washington Post News Service with Bloomberg News

Send questions/comments to the editors.