CUMBERLAND — No one disputes that it’s a beautiful spot.

The sprawling waterfront parcel is a jewel of the town’s affluent Foreside section, where Spears Hill comes to rest at the edge of Casco Bay. Rolling fields and woodlands lead to a narrow strip of sandy beach, sea grass and clam flats that stretch out to expansive views of Broad Cove and Yarmouth’s Sunset Point and Cousins Island.

“It’s a gorgeous piece of property,” said George Marcus, who lives in the abutting Wildwood neighborhood.

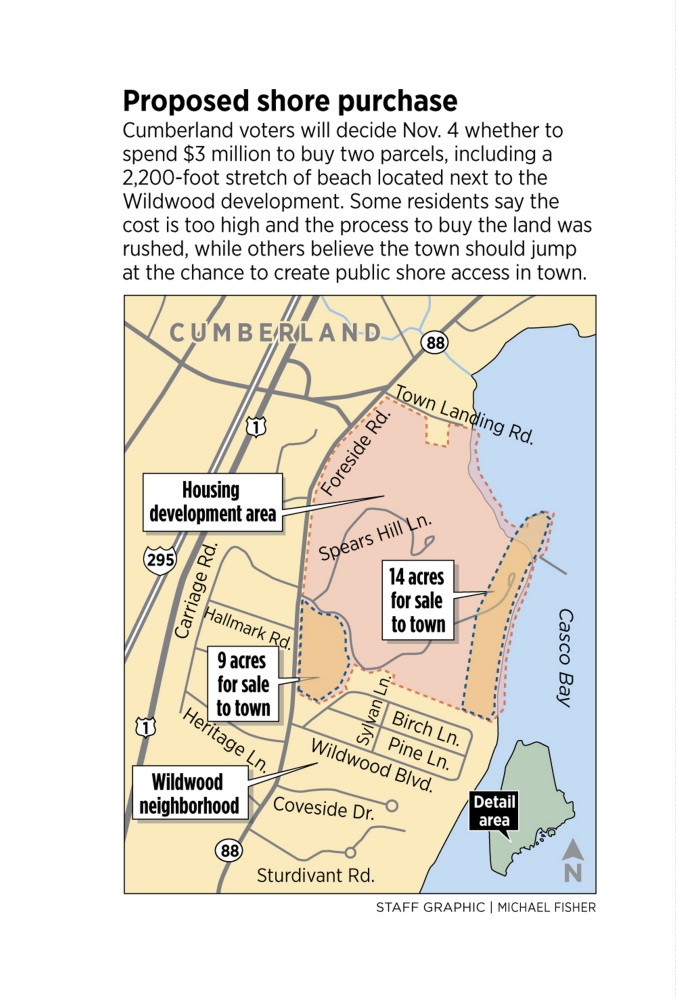

That’s about where agreement ends in a town that’s set to consider buying its first beach for public use on Nov. 4. The $3 million bond referendum would allow the town to purchase a little more than 25 acres of the Payson estate at 179 Foreside Road.

The proposal has deeply divided the community, pitting waterfront residents against their inland counterparts and giving rise to us-and-them rhetoric on dueling campaign websites set up with help from public relations professionals.

Mud has been slung from the lectern at Town Council meetings to the sidelines at soccer games, with targets ranging from the longtime town manager who came up with the idea to Wildwood neighbors who are viewed as opposing public access next to their private beach.

The referendum proposal includes nine acres near Foreside Road, a half-mile road and right of way to the waterfront, and 14 acres of shorefront and tidal property that features a nearly half-mile-long beach and a 220-foot-long pier.

On Sunday, plans were announced to develop a 1.5-mile public hiking trail around the entire estate if the referendum is approved.

The town would buy the land from developers who have negotiated a purchase-and-sale agreement to acquire 104 acres of the Payson estate and plan to develop a 10-lot subdivision.

As public tensions have risen over the vote, the developers’ deal with the Payson heirs has turned hostile in recent weeks and is scheduled for a court hearing Monday afternoon.

Supporters of the referendum say $3 million is a fair price for an extraordinary opportunity in a town that has 3.7 miles of coastline but negligible public access; there are two small, carry-in boat-launch sites off Foreside Road.

Harland Storey is one of several longtime inland residents who have given emotional public testimony in support of the town’s proposal. He questioned the “selfishness” of townspeople who have shorefront access and don’t want to share it.

“It’s the best shorefront access that will ever be available to the town,” said Christopher Franklin, an inland resident who is executive director of the Cape Elizabeth Land Trust and a spokesman for the Cumberland Ocean Access Coalition.

“These opportunities come along once in a generation and often you get one shot,” Franklin said. “In this case, it’s well worth the investment.”

Opponents question the cost, transparency, legality, feasibility and desirability of the town’s proposal, emphasizing a variety of drawbacks to the site, from the slope to the water’s edge to the fact that only about 500 feet of beach remains exposed at high tide.

“I’m concerned about the way this deal came together,” said Sarah Steinberg, an inland resident and interior designer who is a spokeswoman for the opposition.

Steinberg said she agrees that it’s “an amazing property,” but she thinks Cumberland residents are “going to be disappointed with this particular access point. I wouldn’t carry my boat that far.”

They also question the value of the property given the limited, low-impact recreational uses that would be allowed under a conservation easement. At the same time, they worry that the town will violate the easement, despite assurances to the contrary. And residents of Wildwood – an adjacent neighborhood of 65 year-round homes with a private beach that extends beyond the Payson property – emphatically deny that their opposition is a “not in my backyard” reaction.

“That’s a fabrication by people who like to cast it that way,” said George Marcus, one of several lawyers who live in Wildwood and oppose the referendum.

“We’re being asked to vote for a $3 million proposal and we still don’t know what’s permitted on the property,” Marcus said. “I wouldn’t spend $3 million that way. We would welcome appropriate uses. We just don’t know what they’re going to do with it.”

Town officials and the Chebeague and Cumberland Land Trust, which oversees the conservation easement on the Payson estate, have publicly outlined and endorsed low-impact uses of the property (hiking, fishing, kayaking, picnicking, etc.) with a drop-off area and limited parking at the waterfront. A parking lot with 25 to 35 spaces has been proposed for the parcel near Foreside Road.

The trust’s board of directors has determined “that expanded access to the property, which is permitted under the easement, if managed properly, can occur while still protecting the natural and scenic features of this remarkable property.”

Opponents also question the motives of Town Manager Bill Shane in tapping lead developer Nathan Bateman to buy the entire Payson estate – which was on the market for $6.5 million – and then sell part of it to the town to fulfill a longstanding goal to acquire public waterfront access.

The town and Bateman split the $9,000 cost of a joint professional appraisal that found the targeted 25 acres, including all of the waterfront, to be worth $3.2 million. Opponents commissioned their own appraisal, which came in at $400,000.

“The town put this deal together without negotiating at all and met the developers’ price,” Marcus said, noting that voters are being asked to pay market value for land with limited use.

Marcus acknowledged that $400,000 might be too low and pointed to two waterfront properties currently for sale – two acres with a 350-square-foot cottage at 17 Sea Cove Road that’s listed for $1.2 million, and 1.6 acres at 12 Town Landing Road that’s listed for $850,000.

Supporters say they’re OK with the $3 million price tag because the developers have agreed to sell the town the best part of the Payson estate – a private beach – which reduces the resale value of the 10-lot subdivision by $3.2 million.

Neighbors aren’t the only ones upset about the town’s plans. Peter Robbins, lead negotiator among the Payson heirs, declined to discuss the pending land sale or the referendum during a recent walk of the property.

However, he voiced his concerns at a July 28 Town Council meeting, where he noted the “duplicity” of the developers and questioned how the town could “anoint a most-favored developer.” He also described the town manager as “dishonest” and “disingenuous” and questioned why Shane didn’t approach the Payson family directly about the town’s interest in buying the waterfront access.

Explaining his motivations, Shane said he learned that the property was on the market in May and was concerned that such a desirable property would be snapped up before town officials could act. He also was aware that other efforts to establish or preserve public waterfront access have faced significant neighborhood opposition.

Shane said he reached out to Bateman with the Town Council’s blessing because the developer had done good work for the town in recent years. In 2011, Bateman’s company responded to the town’s request for proposals and was selected to convert the former Drowne Road School into subsidized senior housing and build single-family homes nearby.

“We have a very good working relationship,” Shane said. “I think the developers see the benefit of what we’re trying to do. There are some who say we should get (the 25 acres) for free, but you can’t extort land from a developer. I think it’s a fair price and I think it will be viewed as a bargain by future generations.”

With the referendum just eight days away, tension around the related land deals will likely escalate Monday afternoon, when developers Bateman and Peter Anastos are scheduled to be in Cumberland County Superior Court to defend their purchase-and-sale agreement with the Payson heirs.

While the dispute focuses on a $15,000 fee that was paid to extend the agreement, court papers show growing acrimony between the heirs and the developers over the public purchase.

The developers claim the heirs are trying to scuttle the deal because Anastos refused Peter Robbins’ request for half of the $3 million that the town would pay for 25 acres. In a responding affidavit, Robbins acknowledges talking with Anastos about the “adverse effects” of the town’s proposal on the value of property that Payson heirs will retain, but he denies asking for part of the $3 million.

Bateman said the outcome of Monday’s court hearing won’t undo either the developers’ plan to buy 104 acres from the Payson heirs or the town’s plan to buy 25 acres from the developers.

The heirs claim that a real estate firm representing both the heirs and the developers deposited a $15,000 contract extension fee into the wrong bank account. If the judge decides that the firm’s action voided the developers’ right to extend the agreement until after the referendum, Bateman said he’s prepared to complete the sale immediately to preserve the plan.

“We’re so disgusted, we want to see it through to the finish,” Bateman said.

In recent days, the developers have sweetened the pot, offering to allow the town to develop a 1.5-mile hiking trail around the entire Payson estate if voters approve the referendum. Bateman acknowledged that he has helped to promote the referendum, including having his PR team, Chris O’Neil and Mark Robinson, help to organize the Cumberland Ocean Access Coalition and set up a website, www.shorefront4all.org, in response to a groundswell of public opposition. Soon after, referendum opponents set up their own website, www.votenopaysonbond.com, with help from Wildwood resident Elizabeth Baldacci, a partner in Baldacci Communications.

“We (got involved) as soon as we realized we had kicked a hornets’ nest,” Bateman said. “We think we’re doing a good thing for the town. I felt a real obligation to give the town of Cumberland its last opportunity for waterfront access. The town being involved doesn’t make this any more or less lucrative for us. If it’s just a private executive subdivision, we’ll just move forward with that.”

Baldacci and other opponents say they want voters to reject the town’s proposal so residents can take the time to consider other options. They say they don’t oppose public access to the waterfront and note the potential to open all shorefront in Maine for public use. They dispute the notion that this is a last-chance deal.

“If I had a buck for every time someone told me it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, I’d be a rich man,” George Marcus said. The potential for lawsuits if the referendum is approved largely depends on what the town does with the property, he said.

For his part, Town Manager Shane, who’s an inland resident of the town, is floored by the intensity of opposition to the referendum. He doesn’t understand arguments against giving townspeople an opportunity to stroll along the shore in their own community.

“This is truly a piece of property that’s worth acquiring and protecting and maintaining for public access,” Shane said. “The rest is like a bad TV movie and I don’t know how it ends.”

This story was updated at 11:25 a.m. Oct. 28, 2014, to correct the order in which the competing campaign websites were created.

Send questions/comments to the editors.