Maine’s bear-hunting referendum represents more than a philosophical struggle between animal-welfare activists and those who support the state’s bear-hunting practices.

The most striking difference between the two sides is the source of their campaign funds.

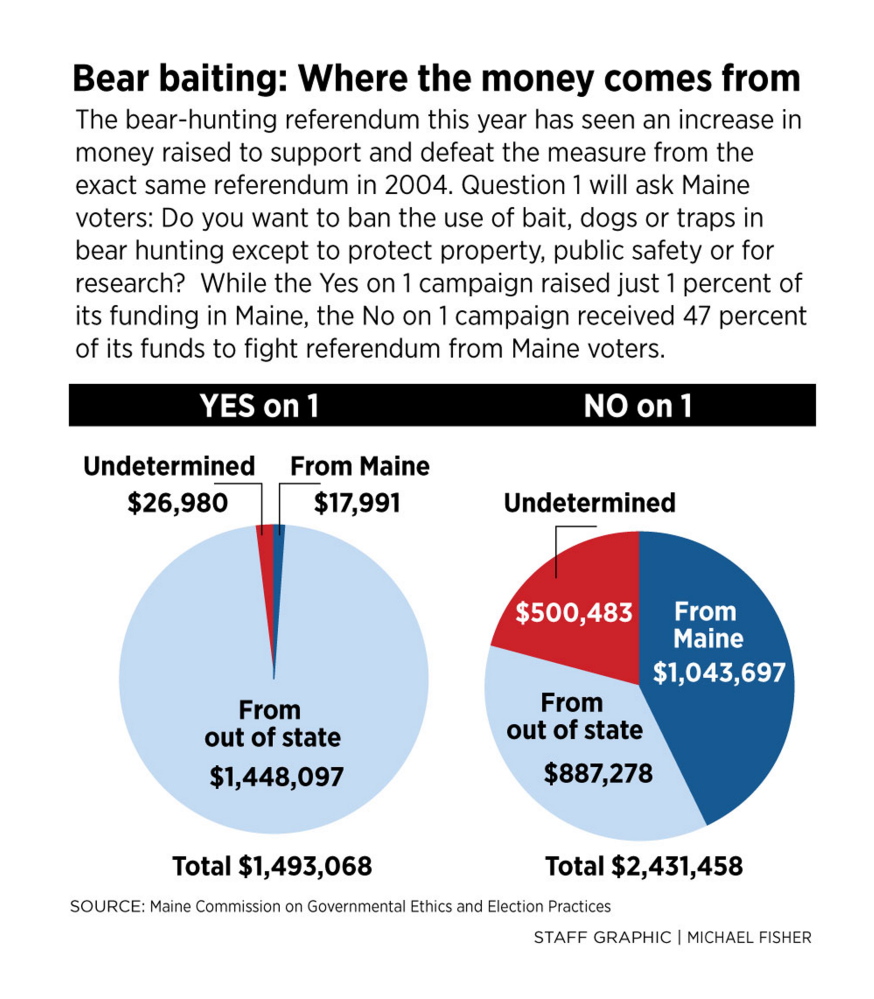

Mainers for Fair Bear Hunting, the group asking voters to ban the use of bait, dogs and traps by bear hunters in Maine, raised more than $1.4 million in campaign funds through Sept. 30. Only 1 percent – $17,991 – is from Maine donors, according to the Maine Commission on Governmental Ethics and Election Practices.

The coalition of groups campaigning against the ballot measure, has raised $2.4 million – at least 43 percent of which comes from Maine donors.

Furthermore, proponents of the ban have received at least 96 percent of their donations from the Washington, D.C., area – home of the Humane Society of the United States – leading opponents to view Maine as a political battleground over hunting traditions.

Question 1 on the Nov. 4 ballot asks Maine voters: “Do you want to ban the use of bait, dogs or traps in bear hunting except to protect property, public safety or for research?” A similar referendum was defeated by Maine voters in 2004 by a margin of 53 percent to 47 percent.

Supporters of the ban say stalking black bears without the use of bait, traps and dogs is enough to control numbers without these hunting methods, which they call inhumane. They argue the black bear guiding industry’s use of bait has caused a spike in bear numbers in Maine, and that without bait the bear population will decline naturally.

But opponents, including state biologists, point to growing bear populations in other states where hunting with bait is illegal, such as Massachusetts. They say a further swell in bear numbers here will threaten public safety in more populated areas.

According to the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife, the state’s black bear population, the largest in the eastern United States, has increased from 23,000 to more than 30,000 in the past 10 years.

Both campaigns have raised more money leading into the 2014 referendum than they did 10 years ago, when proponents raised $1 million and opponents collected $1.6 million – outpacing an inflation increase of 26 percent in the past decade.

Mainers for Fair Bear Hunting has received the vast majority of its 2014 funds – $1.44 million of $1.49 million total – from the Washington, D.C., area. Mainers rank a distant third among its donors, behind those in Maryland and Washington, D.C., where the Humane Society is based.

Katie Hansberry, campaign manager for the group, also is director of the Humane Society’s Maine chapter.

“The Humane Society of the United States represents tens of thousands of Maine supporters that want HSUS as part of the Mainers for Fair Bear Hunting coalition,” she said. “We have well over 1,000 individual donations from people who care about putting an end to the cruel and unsporting practices of bear baiting, hounding and trapping.”

Opponents see Maine’s referendum as a larger political battle that could be played out around the country.

“The perception nationally is that (the Humane Society is) an anti-hunting group, not just on bear hunting, but all hunting,” said David Trahan, executive director of the Sportsman’s Alliance of Maine. “And people are worried in a state like Maine with deep roots in our hunting heritage if they win here, they can win anywhere.”

James Cote, the campaign manager for the coalition opposed to the ban, said as he traveled the country in the past year he’s found wide support from hunting groups. Campaign finance records show that opponents of the ban have received donations from 41 states besides Maine.

As many as 15 donors in Ohio contributed as much as $151,300 to help defeat Maine’s ballot measure. In Vermont, 42 different donors gave $339,890, while 48 donors in New Hampshire chipped in $39,000.

“HSUS has begun a ballot initiative campaign resurgence as they did in the ’90s and early 2000s and they are starting here in Maine,” Cote said. “It is important that we send HSUS a strong message that their anti-hunting agenda will not go unchallenged here or anywhere else in the country.”

Another significant difference in this bear-hunting referendum is in the people leading both campaigns.

In 2004, the opponents were led largely by their campaign manager, Edie Smith, who directed the Wildlife Conservation Council, which Cote now leads. This time, opponents have relied heavily on state wildlife biologists, who have actively campaigned in uniform in public debates, on in-house videos and in television ads.

It’s a different approach than that taken by the ban’s opponents in 2004, and Cote said it was a strategic decision from the beginning. Inland Fisheries & Wildlife Commissioner Chandler Woodcock said the decision to send state biologists out to campaign came from Gov. Paul LePage.

“We made that decision immediately because we realized they were the true experts and they needed to have a voice in this debate,” Cote said. “So we made as much effort as we could to make sure IFW biologists got their message to Maine voters.”

It was a decision that led to a court challenge three weeks ago, when Mainers for Fair Bear Hunting filed a lawsuit in Cumberland County Superior Court accusing the department of using public funds to campaign. The group also filed for an injunction forbidding the department from continuing to use state funds on the campaign. A hearing was held on the matter Friday and a judge expects to make a ruling early this week.

“They are outrageously overreaching and misusing government resources and taxpayer money to influence the outcome of an election,” Hansberry said.

Meanwhile, Mainers for Fair Bear Hunting has a more public, high-profile representative in Hansberry, who moved to Maine in 2012.

Last time it was Robert Fisk of Falmouth, the Maine Friends of Animals president. This time the campaign has been led by Hansberry with an assist from Wayne Pacelle, CEO of the Humane Society of the United States.

“HSUS is much more in charge than in 2004,” Fisk said. “In 2004, we were forced to seek outside help because Maine lacks an animal-welfare lobbying group.”

Pacelle has traveled to Maine several times to appear in television debates and speak at public events. He was one of two panelists chosen by Mainers for Fair Bear Hunting to speak for its campaign in a television forum held by the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram and WCSH-TV. He said a larger effort is being made this time in Maine because American culture has changed and animal-welfare issues are given more weight.

“This is happening in our culture: a response to how to treat and care for animals,” Pacelle said in an interview in September. “As a culture we used to do things to animals that now seem harmful and unacceptable. As a culture, we are deciding we can do better.”

Maine’s bear population has increased steadily over the past decade, while hunter success has declined – giving both sides in the campaign more to argue over. Ten years ago the number of black bears tagged by hunters averaged 3,700 annually. The average dropped to 3,000 annually over the past five years.

It is one reason state bear biologists say the black bear population in Maine has grown from 23,000 to more than 30,000 in the past 10 years.

George Smith, the former director of the Sportsman’s Alliance of Maine who helped direct the 2004 ban’s opposition, said the biggest difference for the Mainers fighting the 2014 ban is they’ve been through this fight before. Smith said that experience is why some polls give them the lead.

In a Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram poll conducted in late September by the University of New Hampshire Survey Center, 53 percent of Mainers opposed the ban, while 41 percent supported it and 6 percent were undecided. The poll had a 4.4 percent margin of error.

“We really had to have a grassroots campaign back then. We raised a lot of money in-state. Guides and outfitters did. And it took them years to recover from it,” Smith said. “I traveled the country raising money. We had never done anything like that. And I gave a speech about what we learned several times when it was over. One thing we did learn was, we can do this.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.