Luke Davidson of Maine Craft Distilling makes his Fifty Stone American Single Malt Whiskey literally from the ground up. He starts with barley grown on Crystal Springs Farm in Brunswick, harvested with a vintage grain binder pulled by draft horses named Gus and Marcus. At his 2-year-old distillery in Portland’s East Bayside neighborhood, Davidson soaks the barley in warm water for a day or so, then spills it out onto a framed section of the distillery’s concrete floor, where it is raked and dried for a few days until the grain starts to split and dry, or “malt.”

This archaic procedure is called floor-malting; it is practiced at only a handful of other distilleries in the country – all of them small-batch distilleries where distillers like Davidson are devoted to age-old methods for producing spirits. Close on the heels of Maine’s micro-brewing boom, and reflecting the interest in all things artisanal, craft distilling is on the rise. Just five years ago, there were three small-batch distilleries in the state; now there are eight, with a ninth under way in a former mill in Biddeford. Including Maine Craft Distilling, five of those now in operation are making whiskey. The others are New England Distilling and In’finiti Fermentation & Distillation in Portland, Sweetgrass Farm Winery and Distillery in Union and Wiggly Bridge Distilling in York Beach.

As you might expect from Maine entrepreneurs, each is doing things in his own way.

“I’m using 18th-century technology,” says Davidson, who built his first still, named “Frankenstill” from a giant, stainless-steel drum originally used in a tomato juice factory. To add a slight, smoky flavor to his whiskey, reminiscent of Highland-style single-malt Scotch, he smokes a small amount of the malted grain with peat from Washington County and locally harvested seaweed. He’s even aging some of his whiskey in barrels handmade by South Portland blacksmith Ed Lutjens from Maine white oak.

“It’s total terroir; 100 percent is Maine,” Davidson says.

MAINE’S DISTILLING HISTORY

The earliest Maine distilleries – like those in the rest of the colonies – produced rum. According to the Maine Historical Society, “ships carrying fish, produce, livestock, and box shooks (wood pieces for making boxes) to the Caribbean returned with sugar and molasses. Portland capitalized on this trade by building sugar refineries and rum distilleries.” In the early 19th century, a number of factors, including the abolition of slavery, contributed to the end of trade with the West Indies. With the molasses supply dried up, Maine distillers turned to plentiful grains to make whiskey, which was the dominant American spirit for decades before vodka stole the scene in the 1960s.

Whiskey is well on its way back to the top. In a briefing to the trade last February, the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (DISCUS) reported that 2013 was the “first year in memory all whiskey categories grew.” This whiskey “renaissance,” as they term it, is due in part to America’s craft distillers, whose numbers have surged from 90 in 2010 to more than 400 in 2014, according to DISCUS.

The American Craft Distilling Institute puts the number even higher: 550, “with another 150 to 200 that are either under construction or in the paperwork process,” Andrew Faulkner, managing editor of the institute’s Distiller Magazine said in an email. “We are especially excited about Maine right now because it has a great mix of distillers surrounding the Portland area,” he wrote.

While beer brewing and distilling attract a similar type of creative entrepreneur, distilling is a much more complicated, time consuming and expensive process. And making whiskey is an even deeper dive. So-called white spirits – vodka, gin and rum – can be distilled and bottled relatively quickly because they don’t require aging. But a whiskey’s characteristic flavors and caramel color come from barrel aging, which can take anywhere from a few months to many years.

“It’s an expensive venture putting up whiskey,” says Ned Wight of New England Distilling, whose Gunpowder Rye Whiskey is aged for 12 to 15 months before it is bottled. “You put in all your labor, all your materials and all your utilities – you spend it. And then you wait.”

NEW ENGLAND DISTILLING

Wight knew what he was in for when he opened his distillery on Evergreen Drive in 2012. His great-great-great grandfather founded the Sherwood Distillery in northern Maryland, which made Sherwood Rye Whiskey from the 1850s until it was shut down during Prohibition. When the law was repealed, his great-grandfather and grandfather resumed making rye whiskey at the Frank L. Wight Distilling Company, and later at the Cockeysville Distilling Company, until it closed in 1958, rye having fallen out of favor.

Today, thanks to the renewed interest in cocktails, rye whiskey – bourbon’s spicy cousin – is popular once again. Wight’s Gunpowder Rye, named for the river in Maryland that ran by the Sherwood Distillery, is shipped as far as New York City. In retail stores, it sells for $45-$50 a 750 ml bottle.

To make it, Wight uses rye from Maine’s Benedicta Grain Co. and Aroostook County barley malted in Montreal, both processed by Maine Grains in Skowhegan. Midwestern-grown rye is part of the mix, but Wight says he hopes to eventually be able to make his rye whiskey with all local grains.

“It’s not a shortcoming of the rye grown in Maine,” he said. “The quality of the grain is very good. It’s just that the way it is processed before it gets to us requires extra steps on our part, and we’re working to tweak that.”

The grains are “mashed” (soaked) in hot water for two hours, cooled, and then yeast from Maine Beer Company in Freeport is added for fermenting. (Making beer produces extra yeast, which Maine brewers often share with distillers instead of discarding.) After three days, the spent grain goes to a farmer to feed his animals and the liquid, often called “distillers beer,” goes into one of Wight’s two Portuguese copper pot stills, where it is distilled twice before the young, still clear whiskey is transferred into new, white oak barrels for aging. The barrels are charred on the inside, which helps to seal the wood and add flavor to the spirit stored inside. They rest on racks Wight found at the defunct Sherwood Distillery, where they once held the rye his great-great-great grandfather made.

WIGGLY BRIDGE DISTILLERY

Whiskey can be made from any grain, alone or in combination. Like most distillers, Wight will not disclose his mash bill – the industry name for the formula or recipe detailing the percentage of each grain. But Dave Woods, who owns Wiggly Bridge Distillery in downtown York Beach with his son, David, is happy to reveal the mash bill for his bourbon: 58 percent corn; 37 percent rye and 5 percent malted barley.

By definition, bourbon must be at least 51 percent corn and aged in new, charred, American white oak barrels for at least two years before bottling. “Baby” bourbon can be aged for less time. In May, Wiggly Bridge released its first batch of baby bourbon, aged for 10 months. The label-less bottles are printed with soy ink directly on the glass; the 750 ml. size sells for about $60.

“I like a high-rye bourbon, so that’s what we have,” said Woods, who named his new distillery after the York landmark, the world’s smallest pedestrian suspension bridge (spelled Wiggley). “It has extremely smooth, muted flavors, so you’re getting a little bit of the vanilla, a little bit of the cinnamon, a little bit of the oak and smoke. It’s a very good introductory bourbon.”

Like many distillers large and small, the Woodses use grain from Wisconsin giant Briess Malt & Ingredients Co. for their whiskies, which in addition to the baby bourbon include a white whiskey (aged very briefly so it can be called whiskey instead of moonshine) and a true bourbon, which should be ready for bottling by December 2015, Woods said.

“I believe in local, but I couldn’t take a chance with a farmer who knew how to grow things but didn’t know how to grow things with a certain starch content,” he said. “Getting into this, I’m self-taught, I wanted to take the grain quotient out of the formula.”

His plans include a five-grain whiskey, using millet, spelt, quinoa, corn and rye. “Eventually, we will be doing small-batch releases of local grain products,” he said.

A well-known Southern Maine business owner whose enterprises include car washes and an oil and gas company, Woods built his own 60-gallon still, using a photo he found in a book as a guide. “We scaled the picture up and laid out sheet copper and cut it out by hand.”

His barrels come from a cooperage in the Midwest, built to Woods’ precise specifications. “We only use Pennsylvania oak, Western slope. The setting sun versus the rising sun on the mountain produces a different sugar content in the tree. Makes a sweeter product.”

Since he opened Wiggly Bridge in May, Woods says he’s run out of whiskey three times and has scaled back the days his tasting room is open from seven days a week to four. He and his son are building a 250-gallon still in their new distillery, housed in a former 1880s barn on Route 1, which is expected to open next spring.

SWEETGRASS

While Maine’s newer distilleries are busy trying to keep with customers’ demand, the first person to make Maine whiskey in the modern age is content to let them wait.

Keith Bodine, who founded Sweetgrass Farm Winery and Distillery in Union with his wife Constance in 2005, is aging a Scotch-style whiskey that won’t be ready until 2018.

“The oldest whiskey we have in barrels has been there three and a half years or so. We figure seven years,” he said. “But it might be six – I really like the direction it’s going in. I like the flavors and the aromas.”

The Bodines, who opened a tasting room on Fore Street in Portland earlier this year, are known for their Back River gin, Three Crow rum, fruit wines, apple brandy and a host of other products. Keith said he had wanted to make whiskey for years, but was committed to distilling it from Maine-grown grains.

“We eventually figured out that the potato growers in Aroostook County were also growing barley and we made contact with a malt house,” he explained.

The Maine barley used in his yet-unnamed whiskey is malted in Montreal and shipped back to Maine, specifically to Union, where Bodine mashes, ferments, and distills it twice before putting it into 55-gallon used bourbon or wine barrels to age.

“We could probably do smaller barrels and age it for a shorter time, but the complexity seems to come out in the larger barrels,” he said.

Bodine, who was trained as a winemaker, had to learn to work with grains. “We don’t have a lot but it’s going to be very good. We’ve been making it more in succeeding years and trying to ramp up production slowly. I have people offering me money every day to hold a case. It will be interesting.”

IN’FINITI

Eric Michaud, proprietor of In’finiti Fermentation & Distillation on Commercial Street in Portland, has an ambitious goal for his combination brewery-distillery-restaurant.

“The plan was and still is to stock our bar (ourselves) with anything you need to make a cocktail,” he said, citing absinthe, gin, Japanese shochu and honey-based and Calvados-style spirits among those he wants to make in-house. His brother Ian, a former Broadway stagehand whom Eric convinced to return to their home state, is the head distiller.

Despite its thoroughly contemporary name and look, the model for In’finiti is an Old World one. Eric, who has traveled extensively in Germany (and who also owns Portland’s popular Novare Res Bier Cafe), references Bavarian breweries as his inspiration.

“Every brewery is also a brewpub,” he said. “Our business plan is quite different (from other distilleries); we never intended to be a full-scale production facility.”

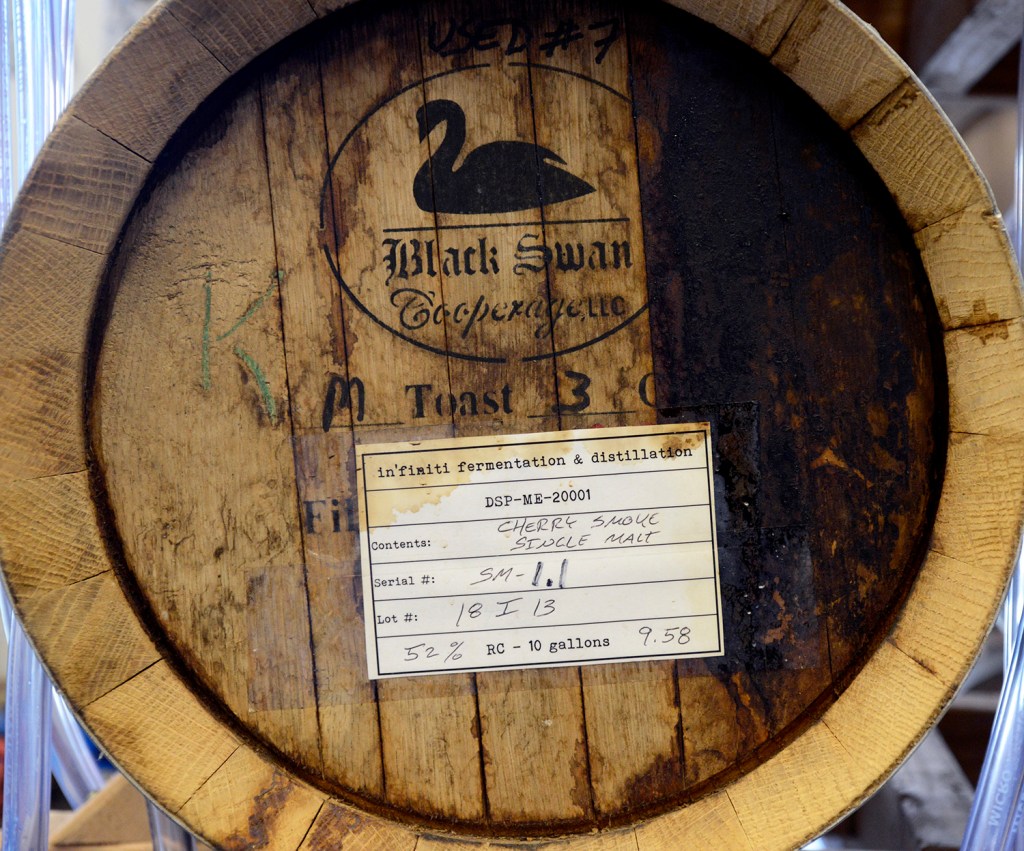

In the 18 months or so since In’finiti opened, the Michauds have already produced white spirits: rum, vodka and a white whiskey – Old Port White Oat, made from organic, Maine-grown oatmeal. This winter, they plan to release four aged whiskies: baby bourbon, rye, an aged version of the oat whiskey and a cherry-smoked single-malt – all under the Old Port label.

Since whiskey starts as beer (see sidebar, “How It’s Made”), having a brewing operation on site would seem to be an advantage. However, federal law requires the brewhouse and distillery to be completely separate, from a business standpoint and physically. At In’finiti, both operations are visible from the restaurant and bar, but a glass-walled hallway runs between them.

To make their bourbon, for example, a mixture of all-organic, Maine-grown corn and rye – plus a small percentage of malted barley from Briess – is mashed and fermented in the brewhouse in an open fermenter, using as much of their own yeast as they can. The “distillers beer” is then transferred across the hall to the copper still, 100 gallons at a time, before being barrel-aged and finally, bottled in In’finiti’s distinctive, apothecary-style bottles with wooden tops.

Among their many projects, the Michaud brothers have something in the works most Americans have probably never heard of – bierschnapps, a high-proof spirit made in Bavarian brewpubs from the “leftover dregs” after brewing, Eric said.

“The difference between whiskey and distilled beer is hops,” explained Ian. “Because bierschnapps is being distilled at a higher proof, it has less of a grain flavor … the botanical floral flavor of the hops comes through.”

Will there be a market for bierschnapps in Maine?

In a state where vodka made from potatoes (Cold River), beer brewed with oysters (Marshall Wharf) and chocolate cookies baked with rye (Standard Baking) have all been embraced, it’s a good bet.

“The people that live in or come to visit Maine are an adventurous group,” said Ned Wight. “They’re willing to try new things – I love it.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.