Mainers know a thing or two about winter storms. But few have encountered a blizzard as epic as the one Bill Roorbach conjures up in his compelling new novel, “The Remedy for Love.”

As the snow begins, we meet the two main characters, Eric and Danielle, as they’re standing in the checkout line at the local Hannaford. She’s a former teacher, 30-ish, scruffy, a few dollars short on her groceries; he’s a small-town attorney who offers to pay the shortfall and give her a lift home. So begins the tale of two strangers, stranded together in a cabin, during a life-altering storm.

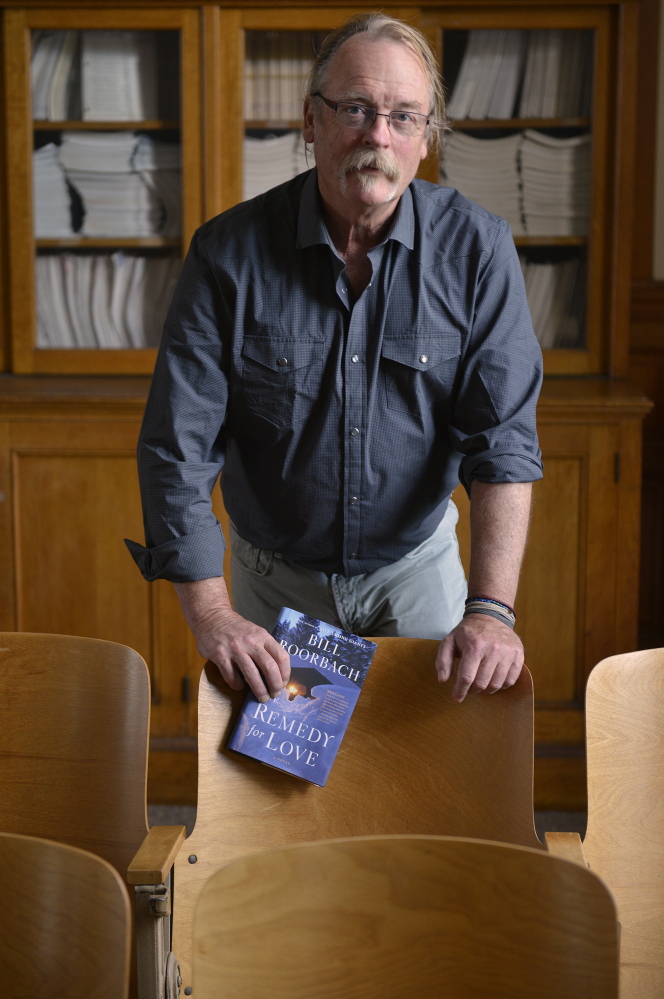

Roorbach, who’s acclaimed as an author, teacher and book doctor, has created both a chilling spectacle and a startling piece of nature writing. The blizzard itself becomes a central character in this edgy romantic thriller. Yet, it’s Eric and Danielle who keep us coming back for more.

These days, Roorbach has several balls in the air – a national book tour that kicks off in Portland; a TV series based on his bestselling novel, “Life Among Giants,” in development with HBO; and an upcoming novel, now in its embryonic stage.

He spoke recently from his home in western Maine about storytelling, housebuilding, Homer and the necessary art of revisions. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: You describe yourself on your Twitter page, as “a good writer with bad habits.”

A: I’m 61-years-old. Nowadays my bad habits are staying up late to write and getting up early to hike. I played rock ‘n’ roll when I was a young man. I really got used to staying up all night and sleeping all day. And I find, as I put my professor life behind me, that I’m reverting to the rock ‘n’ roll schedule in some ways. I think it suits me. As I writer, I get to go back and keep playing, to put that missing solo in, and rearrange the notes as I see fit.

I also did a lot of construction work in my youth. When I was younger, I’d feel like, well, if everything goes to hell, I can always go build a house. You know, when you’re building, you come back the next day and everything’s exactly as you left it – the problems and the triumphs. But with gardening, which I do a lot now, you come back the next week, and everything’s changed. I see writing both ways.

Q: Have you ever had a first draft that’s very close to what ends up on the printed page?

A: Certainly parts of everything. There might be a stretch of 10 paragraphs that never get changed. But very often, with my fiction, there’s the revelation I have when I’m in bed, or taking a hike: Oh, my gosh, what if, instead of his driving off, she drove off, and it changes everything. Without a single qualm, I will just dump a hundred pages and let her drive off. I’ll just follow that new thread.

Q: You’ve written novels, short stories, essays. If you could write in only one genre, which would you choose?

A: I do love them all. But fiction was my first love and it continues to be my true love. Why fiction? Because I love so much being in the middle of a story and carrying these people around, who you can control, but who also start to have lives. It’s fascinating how it works. You get to know them, and I just love being in that other world.

Q: Is there a human need to tell stories, or a storytelling impulse?

A: I do think it’s a basic human need. It’s one of our survival mechanisms – and our own. Other species can’t do it. So I can hear from my forebears, or from the older kids, about the dangers out there and how to confront them. It starts as a survival skill, but it also becomes entertainment.

There are people who are good at telling these stories, and people who are dazzlingly good at telling these stories, and remembering them, like Homer. They develop status, because they can bring to life something that’s really just a survival mechanism. They can make us see who we are and why.

Q: Who’s telling the best stories right now?

A: I think there are a lot of great, great stories in books still. There’s a lot of great stories on TV – those multi-year shows, the good ones.

I used to be such a snob about television. But more and more, that’s where people are getting their narrative fix. I just realize that people want their narrative.

If it’s a great story, I love it. Any medium. Music’s a form of storytelling, argument is a form of storytelling, so are essays. You might think there are no stories here, but the argument itself is a story.

Q: You’ve talked about the actual snowstorm that got you thinking about the idea for “Remedy for Love.” The notion of “the storm of the century” may have seemed hyperbolic even 10 years ago, but not now.

A: I had a building fall down two years ago. The storm was so big, snow fell off the trees and pushed it just far enough that it completely gave in and collapsed. That was part of the vision in my head.

The other thing is, the novel is about a couple of people stuck in a cabin together. But it’s a much bigger story if it starts to be about climate change, and it starts to be about the town, and the collateral damage of war. Then you can focus all the action in a small sphere.

Q: “Remedy” is such an intimate book, with these two complicated, engaging characters, especially Danielle. She’s like a human curveball. How did you channel the Danielle character?

A: That’s a hard question. Well, I really like women. I don’t think women and men are all that different, on many levels. If I’m just willing to think about my heart, I can think about any human heart. You have to look past all the surfaces.

I had a very small experience of bumping into someone in trouble in a grocery store, and I tried to give her a little help, dropped her off and left. But what if I had stayed with her? Who is she?

So, as I start writing, the real person I was thinking of disappears utterly; I can’t even picture her anymore. And this young woman, Danielle, emerges and she’s very complete after just a few pages – and she starts telling me what to do!

There are a lot of angry people around, but you don’t always know until they’re under pressure. Danielle is someone who’s willing to be exactly who she is. And yet, who is she? She’s full of lies and deception. I really like the way the characters keep changing in front of you, like you’re looking at a dodecahedron.

Q: How long did it take to write the book?

A: All together, I’d say it was about three years. When you change the beginning a lot, that means the end was practically useless. I just had to throw it away mostly.

Q: When you realize that an entire section has become obsolete, is that frustrating or just part of the process?

A: It’s part of the process. Let’s say you had a plan to swim across a lake. When you get to the other side, you can’t say that the first third of the swim was irrelevant. You had to do “A” to get to “B.” To me, there’s no pain of any kind in letting go of pages, ever. I’m just focused on getting the story to where I love it.

You know, that’s a really hard concept to teach newer writers, that they should be happy to abandon stuff. They want to keep it, they want to tinker with their words. But you have to be pretty ruthless. With “Life Among Giants,” I had a draft that was 600 pages, then cut it back to 400 – just reams of pages that you leave behind. Some of them were very good, but it just got too long.

With the new book, I had a lot fewer wrong turns because early on, I got the trajectory in my head. I was able to move quickly through it.

But I’d reach the end and realize that these two people I’d gotten to know weren’t on the page at the beginning. So I’d go back and make sure they were emerging early. And then I’d rewrite again.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews. Her work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News.

Send questions/comments to the editors.