Ana “Baby” Pemba is neither a legal resident of the United States nor an “illegal alien.”

What Pemba is – along with hundreds of other asylum seekers from sub-Saharan Africa living in Maine’s larger cities – is a woman in limbo: caught in between a former life to which she feels she cannot safely return and a backlogged U.S. immigration system that must decide whether she can stay here and start a new life. She also is caught up in a brewing Maine election-year battle over welfare reform.

Pemba was a rising gospel singer in Angola when she said she was targeted by violent partisans angry about whom she had performed for and about a song denouncing abuse of women and children. Eight months pregnant and fearing for her life, she entered the U.S. with a tourist visa in late 2013 and filed for asylum roughly six months later when her visa expired, she said.

Like other asylum seekers, Pemba said she was drawn to Maine, in part, because she heard communities here provide financial help to immigrants as they apply for asylum and wait for legal working papers. Now, Maine’s fast-growing population of asylum seekers – located largely in Portland and Lewiston – is at the center of a political and legal fight led by the administration of Gov. Paul LePage that could eliminate access to the state- and locally funded welfare program known as General Assistance.

“We cannot afford the asylum seekers,” said Lewiston Mayor Bob Macdonald, a supporter of the Le- Page administration’s push to end welfare benefits for undocumented immigrants. “Do they have skills? Absolutely, some of them have skills. And we could certainly use them. But we don’t have the money.”

Pemba said she appreciates and needs the support, but would rather not have to ask for it.

“All we truly want is to leave your assistance and be independent, but how are we going to do that if we are not allowed to work in this country?” Pemba asked.

Thousands of people from war-torn or politically troubled nations in sub-Saharan Africa have arrived in Maine in recent years on their own with visas that allow them to visit, work or study on a temporary basis, only to seek asylum so they can stay permanently. Asylum applicants wait in a fuzzy legal status in which they are considered to be undocumented but protected from deportation. And at the same time they are prohibited by federal law from working for at least six months – and sometimes much longer.

Meanwhile, the wait for asylum can take years, with a nationwide backlog of applications that is expected to grow because of the surge of unaccompanied minors crossing the southern U.S. border in recent months.

“The backlog is significant and it is definitely getting worse,” said Lori Nessel, professor of law and immigration rights at Seton Hall University School of Law.

POLITICAL BATTLE OVER AID

Maine’s asylum applicants are also now caught up in a political battle that began this spring with LePage’s decision to remove Maine from a small list of states that provide state-funded welfare to asylum applicants.

Citing a 1996 federal welfare-reform law that restricts assistance to undocumented immigrants, LePage vowed to withhold reimbursements to communities that continue to provide state funds to such non-citizens through a program known as General Assistance. The GA program uses state and local funds to provide people who have little or no income with basic necessities such as rental vouchers to prevent homelessness and vouchers for food or medicine.

Critics of the administration’s edict, including Maine Attorney General Janet Mills, said Maine’s assistance program is based on need alone, regardless of immigration status.

The cities of Portland and Westbrook, with help from the Maine Municipal Association, filed suit in Maine Superior Court to block the LePage administration’s policy. The administration countersued last month, attempting to move the issue to federal court.

“I urge all Mainers to tell your city councilors and selectmen to stop handing out your money to illegals,” LePage said in a recent radio address.

This month, the dispute emerged as a wedge issue in Maine’s gubernatorial race.

An attack ad launched by the Republican Governors Association in support of LePage’s re-election campaign highlights the political undertones of two hot-button issues: immigration and welfare.

“Do you think Maine’s cities and towns should continue to use your tax dollars to pay welfare benefits to illegal immigrants? Mike Michaud does,” the ad’s narrator says of the Democratic congressman who is currently LePage’s top threat to a second term.

Immigrant rights advocates bristle at the term “illegal aliens,” especially when used by LePage to describe asylum seekers trying to navigate the federal immigration bureaucracy.

“Someone who fled the country and is going through the asylum process, they are not breaking the law,” said Sue Roche, executive director of the Immigrant Legal Advocacy Project. “They are following the law.”

Macdonald, who also frequently uses the word “illegal,” acknowledged that most asylum seekers in Maine arrive with valid visas but become undocumented after those visas expire. He accuses many asylum seekers of applying for student or work visas under false pretenses because they really intend to seek asylum in the U.S.

Macdonald said those who want to immigrate should apply for refugee status and wait for permission to enter. “If they want to come over here, they should wait their turn just like the Somali (refugees),” he said.

Like asylum seekers, refugees are fleeing persecution. But they apply for U.S. residency while living in another country. And they are resettled in the U.S. through a government program that often works with nonprofit agencies to help refugees with the transition so they do not require General Assistance.

There are no reliable data on the number of undocumented immigrants in Maine, where they come from and how they got here. However, unlike in other parts of the country where an undocumented immigrant is more likely to be someone who crossed a border illegally, an undocumented immigrant in Maine is most likely to be someone who arrived legally with a now-expired visa and is seeking asylum, according to those who work with new immigrants.

There are 587 asylum applicants in Maine waiting for interviews with the federal asylum officers who review cases, according to a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services official. Because the asylum process takes so long, the vast majority of them are sure to have expired visas.

The agency could not provide overall numbers or historical trends about applicants in Maine, the spokesman said. But the entire Northeast region has seen a surge in applications that reflects what has happened in Maine cities.

The number of new asylum applications filed in the Northeast region nearly doubled – rising from 2,928 to 5,633 – between fiscal years 2010 and 2013. And the regional office in New Jersey received more than 3,500 applications during the first six months of fiscal year 2014, well above the 2013 pace.

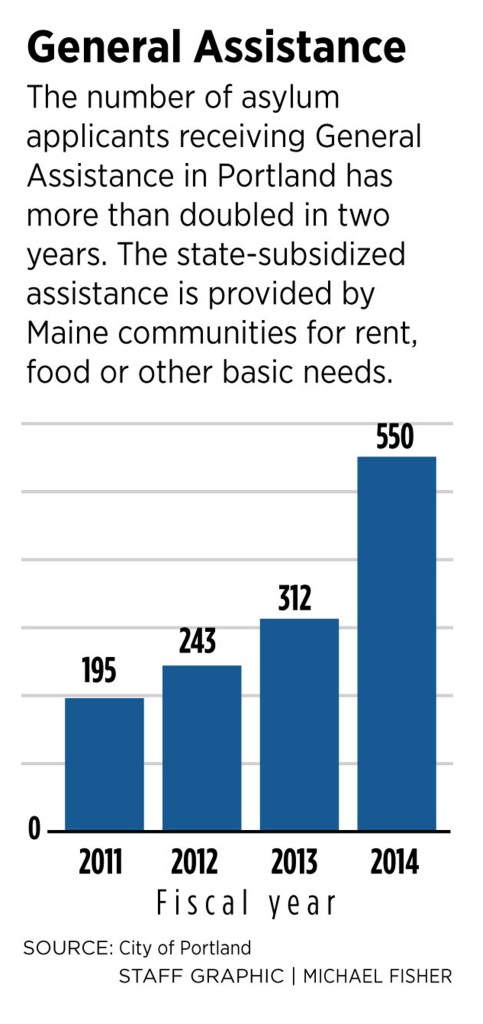

General Assistance statistics from Portland show a steady increase of asylum seekers asking for help. The numbers also show that applicants need help longer because of the backlog in federal immigration cases and delay in asylum decisions. More than 90 percent of asylum seekers receiving assistance in Portland last year arrived from four turbulent African nations: Burundi, Angola, Congo and Rwanda.

For the first 11 months of fiscal year 2014, Portland provided roughly $3 million in General Assistance to 522 households – representing 937 individuals – whose asylum applications were still pending. That figure is up from 312 households and $1.8 million in General Assistance expenditures in fiscal year 2013 – and nearly triple the figures from fiscal year 2011.

The share of the General Assistance budget used to help asylum seekers more than doubled from 15 percent to 33 percent between 2011 and 2014, while the portion paid to non-immigrant clients fell from 72 percent to 49 percent.

SHARING THEIR STORIES

Numerous immigrants who have been granted asylum or hope to be granted asylum shared their stories with the Maine Sunday Telegram in recent weeks – some for the first time publicly. Some were guarded about personal details or declined to be named in this story. Many others declined to speak with a reporter out of fear that going public could somehow harm their asylum application or citing concerns about putting family in Africa at risk.

As is common among asylum seekers who have the means to get to the U.S. on their own, many were professionals in their home countries whose success or outspokenness made them targets – and whose skills might make them sought-after newcomers in Maine under other circumstances.

Dr. Godefroy Watchiba was an infectious disease specialist from the Democratic Republic of Congo who traveled to the U.S. on a visa and later sought asylum after intensifying threats over his refusal to share information on patients with powerful political interests.

Penniless and unable to legally work in the U.S., the physician lived in a Portland homeless shelter for weeks. But he was granted asylum and now holds a green card and is preparing to take the American medical board exams.

“We have doctors and lawyers cutting up chicken and sweeping floors” as they wait for asylum, said Kitty Coughlin, co-founder of the Safe Harbor immigrant assistance program run by Portland’s First Parish Unitarian Universalist Church.

Several of the immigrants interviewed said they chose Maine because it is known as one of the few states to help asylum seekers.

A handful of states – California, Washington, New York, Minnesota and Hawaii – allow asylum applicants or other immigrants who have yet to gain legal status to receive similar forms of government assistance, according to a review of data compiled by the National Immigration Law Center and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Each state has its own distinct programs, with varying rules and eligibility standards, however, and some other states may provide other benefits such as health care coverage or food assistance.

Rehma “Becky” Juma, a 19-year-old asylum applicant from Burundi, arrived in Portland alone in September 2013. The incoming senior at Portland High School will become ineligible for General Assistance this month when her visa expires under the state’s revised policy, although Portland has vowed to defy the LePage order.

“I came to Maine because of General Assistance and they told me that here (people) are kind,” she said. “It’s not like big cities. It is good here.”

Ayman Musa, a 22-year-old from the Darfur region of Sudan, came to the U.S. with a visitor’s visa but decided he could not safely return with his family because of the violence and lack of security there. He came to Portland alone looking for help, and is now renting a room and studying English and on a waiting list to get help with his asylum application.

“Nobody asks me, ‘Why are you here?’ They say, ‘Welcome.’ ”

Those interviewed also told about danger and fear that brought them here.

Pemba, the Angolan gospel singer, sang at gatherings of Angola’s ruling party, the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola. But she also sang at events staged by the rival party – a fact that angered the ruling party, she said. The release of her single “Africa,” which denounced the suffering of women and children, raised tensions further.

Pemba said she was forced to flee Angola for a neighboring country – leaving behind three of her children in the care of relatives – after paramilitary forces searching for her shot two cousins at her home, killing one of them.

Warned by relatives to escape, Pemba used a tourist visa to get away, at least temporarily. Pemba said she had acquired the visa a year earlier to come to the U.S. to work on a CD she was recording, but had never made the trip.

She arrived in late 2013, first settling in North Carolina and then moving to Maine. Her visa expired about six months after she arrived and she applied for asylum around the same time. She is waiting for a permit to work.

She now volunteers and sings with a church choir in Lewiston while learning English, her fifth language.

“We are not lazy. We are hard workers and we want to be independent,” Pemba told members of the Lewiston City Council in July.

BACKLOG OF CASES, LONG WAIT

Pemba, and those in limbo with her, may be waiting a long time for an answer to their asylum requests.

Federal statute dictates that asylum seekers are supposed to be interviewed by an asylum officer within 45 days of filing an application and are supposed to have a decision within 180 days. But the immigration agency had a backlog of more than 40,000 cases earlier this year.

“The people who are getting (asylum) interviews now have typically been waiting about two years,” said Roche, whose legal advocacy organization works with more than 100 pro bono attorneys to help asylum seekers with their applications.

Asylum officers conducted between 30 and 40 interviews in Maine last year, representing well under 10 percent of Maine’s current backlog.

Those seeking asylum say the time spent waiting for permission to work is the most difficult period, and when they most need assistance.

Congress created the waiting period for working papers in the 1990s to prevent people from applying for asylum so they could work while they waited to be denied. Several years later, Congress also declared the undocumented immigrants ineligible for federal assistance programs as part of a broad, bipartisan welfare-reform law.

Watchiba, the Congolese physician, said “I felt like my head would explode” as he waited for the right to work. “It was very hard – and (a) very vulnerable moment of my life,” he said.

Eliminating the waiting period for work permits is one of the few areas where activists on both sides of the immigration debate seem to agree.

“They come here to work,” said Macdonald, the mayor of Lewiston, who views asylum seekers as illegals. “They don’t come here to get in the (welfare) system. … Give them a work permit, no problem.”

____________________

CORRECTION: This story was updated at 2:52 p.m. on Sept. 17, 2014, to clarify the statement of Kitty Coughlin regarding asylum seekers who are working as they wait for their applications to be approved.

Send questions/comments to the editors.