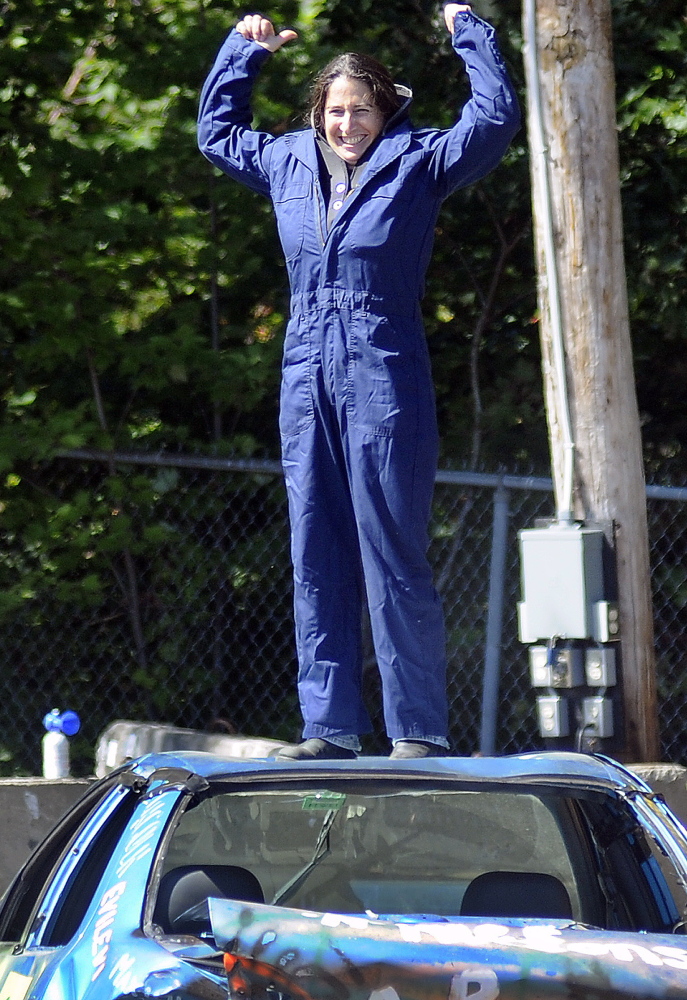

LITCHFIELD — Lezley Sturtevant drove slowly past cheering family and friends, flashing a wide smile and waving out the window. Her car was crumpled like a wad of paper, but it was still moving, ready to pound some more cars into submission.

“She’s running great,” Sturtevant said as her crew used sledgehammers and wrecking bars to force the crumpled metal away from the tires in time for the final heat of Sunday’s demolition derby at the Litchfield Fair. “I didn’t leave my seat. That was good.”

The derby, the first for the fair that wrapped up Sunday, attracted hundreds of people to watch 15 drivers turn their junk cars into battering rams. After starting with a wild crash that sent one of the cars barreling over a concrete barrier into the woods, the end came when one of the last two cars caught fire. The flames were quickly doused by Litchfield firefighters. In between, the crowds – and the drivers – got what they wanted: lots of crashes, lots of fun and a pile of cars to send off to the crusher.

The first winners – there were two because of a ruling glitch – were Jon Averill, of Litchfield, who was driving a 1999 Ford Taurus, and Rick Goddard, of Bowdoin, and his 1995 Ford Escort.

“It’s a good way to take out aggression,” said driver Mike Smith, of Auburn. “A lot of the time I’d like to do it on the road, but I can’t. There are laws.”

There were two Averills who made it through one of four qualifiers to advance to the eight-car final. Matt Averill, Jon Averill’s brother, held on for a long time in the final with the 1997 Cadillac Deville he got from his grandfather.

“We were using it as a parts car,” Matt Averill said. “There was enough there to get it going again.”

Averill said he had never competed in a derby before, but wanted to give it a try when he learned his hometown fair was planning a competition. Averill tried to set up the car to keep running, moving the electrical components, for example, to survive batterings.

“Your engine can stop getting a spark, and you’re dead in the water,” he said.

Averill’s strategy of protecting his engine worked well enough to get him through the qualifiers.

“It was pretty good,” he said of his first time driving in a derby. “There’s definitely some whiplash.”

Sturtevant, too, made it through a qualifying heat in a 1999 Chevrolet Cavalier that was donated by a friend. Sturtevant repaid the favor by painting the name of the friend’s business across the car’s trunk. The roof was painted with sports numbers worn by Sturtevant’s and friends’ children at Oak Hill High School.

“The whole neighborhood is in on it,” Sturtevant said. “It was a cool experience.’

The drivers began arriving a couple hours before the 10 a.m. competition. Lined up in the field across Plains Road that serves as a parking lot, the drivers, their friends and families made last-minute alterations, ripping off sun visors or painting new decorations or names of unofficial sponsors. The new paint jobs were doomed to short lives, however.

“I probably have $40 in it,” said driver Nick Mulherin, of Litchfield, standing outside his 2005 Chevrolet Impala. “The frame is bent so she’s junk. It runs good.”

Jason Patterson of Richmond was competing in his first derby. His 2001 Hyundai Elantra came from close to home: “My mom,” he said with a grin. “It had a transmission problem. We parked it and now it runs.”

Drivers are required to wear helmets, but most chose other safety gear, too – gloves, overalls and even collars to protect against neck strains. The rules and protective gear usually prevent serious injury, said driver Josh Markham of Vienna, who has competed in more than 100 derbies, but they do nothing to prevent aches and pains. Markham said he has twice had pieces of cars, like bumpers, come through a window with enough force to break his helmet.

“Every year I usually have a sore neck,” he said.

Markham, who drove a 1999 Ford Taurus that he bought for $300, said the type of car you use determines your comfort during competition and how you will feel afterward.”The big cars, it’s like riding on a big cloud,” Markham said. “In the little cars, a big hit, you can feel every stitch in the seat.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.