In the winter and spring of 2013, the state of Maine and the Los Angeles Unified School District were both shopping for computing devices to put in the hands of their students and teachers.

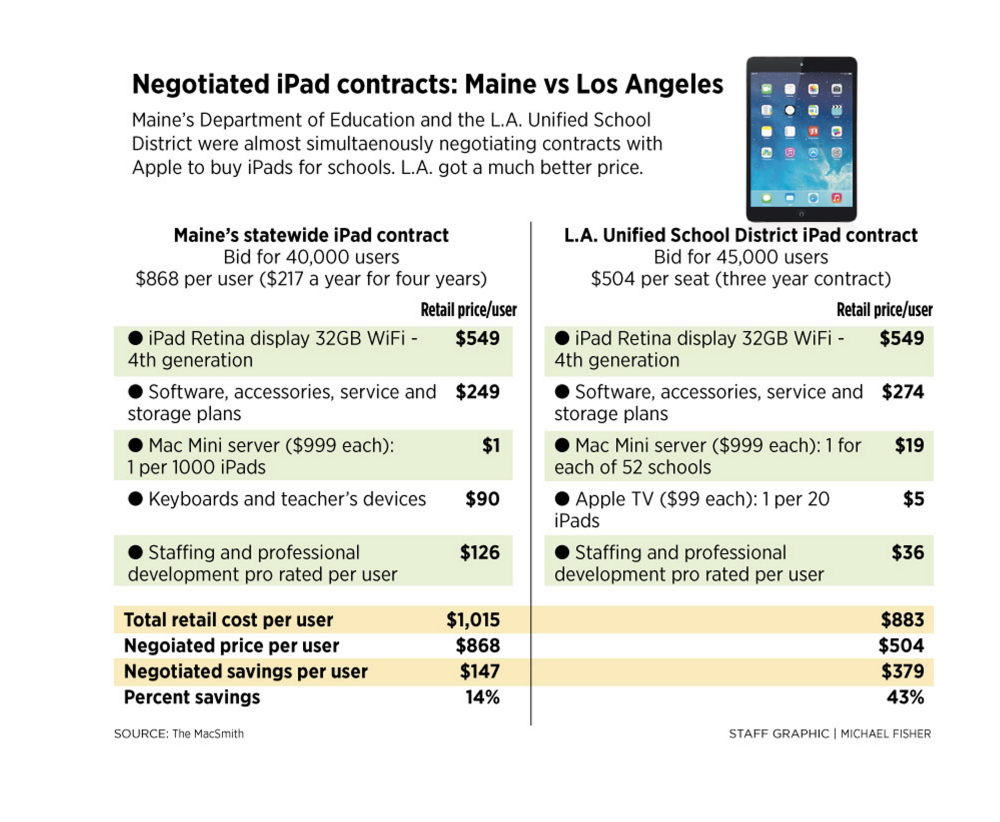

When each finished its negotiations with computer maker Apple, Los Angeles wound up with a much better deal than Maine, even though the contracts were for exactly the same device and a similar number of users. Los Angeles got a 43 percent discount off retail prices. Maine’s discount was only 14 percent.

“Maine grossly overpaid for these devices,” says Stan Smith, owner of The MacSmith, the Falmouth-based business consultancy for Apple users that undertook a detailed comparative analysis of the contracts because he believes the state officials running Maine’s program have too close a relationship with Apple. State officials, when presented with Smith’s calculations, did not dispute them.

Nearly 40,000 Maine public school students and teachers are using iPads purchased under a contract negotiated last year by the Department of Education’s Maine Learning Technology Initiative, known as the “laptops in schools program.” The program provides devices to all seventh- and eighth-graders in the state and negotiates bulk price contracts for high schools that choose to participate at their own expense.

The fact that Maine and Los Angeles were simultaneously negotiating with Apple to equip comparable programs with the same technology offers an unusual opportunity to compare contract prices. Individual school districts in other parts of the country made iPad 4 purchases at the same time, but usually for just a few thousand devices and their cases – not tens of thousands of devices with training, network infrastructure, applications and other features.

Maine and Maine schools have overpaid by about $12 million under the contract compared to Los Angeles, Smith says. According to his figures – which compare the retail prices of the products and services received under each contract – Maine negotiated only a 14 percent discount with Apple, which submitted the bid to provide 40,000 devices to Maine schools. The Los Angeles Unified School District, negotiating a contract for 45,000 users at roughly the same time, ultimately received a 43 percent discount.

Even so, the Los Angeles program has come under intense scrutiny in recent weeks and months over allegations that it paid too much for its iPads and associated curriculum software. Senior officials there are under investigation over accusations of having had improper ties and communications with Apple and content-provider Pearson, and the contract has been suspended.

But officials overseeing the troubled program negotiated a better deal than the Maine Department of Education, says Smith, a longtime critic of the way state officials have handled contract negotiations with Apple, which had been the sole provider of laptops to the state program until last year, when Gov. Paul LePage added Windows-based Hewlett-Packard laptops to the mix of approved devices.

“There was no real negotiation,” Smith says. “Apple came in at a price, and the state of Maine said OK.”

The Press Herald provided Smith’s figures and retail cost estimates to both the Los Angeles Unified School District and the Maine Department of Education to solicit comment or corrections. Los Angeles officials said the numbers were accurate for their program; the outgoing head of Maine’s program, Jeff Mao, did not respond when asked if he had concerns about the numbers or the comparison.

Maine Education Department spokeswoman Samantha Warren questioned making direct comparisons between the programs. “Comparing a single urban school district’s contract to that of a large rural state isn’t apples to apples, and because we weren’t party to LA’s negotiations with Apple, it wouldn’t be appropriate for us to comment on them,” she wrote in an email to the Press Herald.

Apple did not respond to a request for comment.

Leslie Wilson, CEO of the Michigan-based One to One Institute, which advises school districts on programs that aim to put computing devices in each student’s hands, said Maine’s negotiating position may have been weaker than that of Los Angeles, which intended to eventually buy $1 billion in computer devices and networks to supply its 600,000 students.

“Maine is a small state; L.A. Unified is an enormous school district that is extremely high-profile,” Wilson said. “Vendors want to be where the action is. It’s a huge selling point for them to be engaged in these kinds of places.”

But Smith also notes that after Los Angeles negotiated its contract, officials learned that Apple would launch the fifth-generation iPad in late October 2013. Upset that they would be deploying outdated devices just weeks before better ones were available, officials demanded – and got – Apple to give them the new devices at the same price as the iPad 4s, a development reported at the time by the Los Angeles Times and other media.

Maine did not ask for the upgrade.

Los Angeles school officials declined to comment on their renegotiations for the newer devices, but Mao, who negotiated Maine’s contract, told the Press Herald he was unaware Los Angeles had done so.

“We did not push for a fifth generation iPad,” he said by email. “I was unaware that LAUSD did that given they deployed equipment for last fall in parallel with us … and the iPad 5th generation was not released at that time. So I do not know how they could have done it.”

Smith said it would have been easy to do so; schools would just have had to wait until late October 2013 – instead of late September – to issue the tablet computers to students. “If they had told schools, ‘We can wait three weeks or so, and then you can get a new model that will be faster,’ I’m hard pressed to think that the schools would say, ‘No, we want the slower one for the next four years,'” he said.

Smith’s analysis breaks down the two contracts into their individual components, then assigns Apple’s regular retail price to schools to each, allowing a direct comparison of the actual discounts negotiated.

After the Maine contract was negotiated, LePage declared a Hewlett-Packard laptop proposal to be the winning device. But he also changed the terms of the program, allowing schools to choose any of the other four competing devices – including the iPad 4 – as long as they paid any cost over that of the HP laptop out of their budgets.

The vast majority of schools went with the iPad option, nearly 40,000 users in total. Another 24,000 users ended up with the Apple Air laptop. Only 5,500 got the Windows-based HP laptop. None chose an HP or CTL tablet options.

Mao left the department Friday and is taking a new position with the Common Sense Media, a nonprofit in San Francisco that provides “unbiased information, trusted advice and innovative tools” to parents, teachers and policymakers about movies, TV shows, websites, digital curriculum and other media. Mao is joining a new consulting division that aims to assist school districts nationwide who wish to replicate Maine’s program.

“I know (Mao) really hammered these companies to get the best all-around contract in all the things that would help the schools, including replacement and insurance,” Wilson said in Mao’s defense. “Maine is extremely prudent in my observations, and are professional and arm’s length in what they expect in a contract.”

Mao’s tenure as head of the Maine Learning Technology Institute included some controversy. In March 2013 he was found to have been storing his official emails in a way that did not leave backups on the state’s computer networks, and instead stored them and other records on an external hard drive at his residence. The practice – which was exposed after Mao repeatedly failed to turn over emails in response to a public records request by Smith, who was concerned about the way state contracts were being awarded – had been going on since 2004.

Smith eventually received additional emails in response to public records requests, including some showing informal contacts between top state officials and Maine-based Apple officials in the months before Mao prepared the state’s 2013 request for proposals for the statewide computers-in-schools program.

In June 2011, then-Education Commissioner Steve Bowen wrote Mao: “Good meeting with the governor today – got a great piece of intelligence. Apparently, there is a guy from Apple that goes to the country club in Waterville? He told the governor that a year and half out we might be looking at Ipads instead of laptops for the next round – the governor seemed charged up by this idea. SO, he is interested and is interested in talking with you and your team at some point about where we are going with this. The Apple guy, whoever that is, does have his ear, it seems … that could be of use to us…”

Mao wrote back: “That apple guy is Doug Snow, the senior person on Apple’s MLTI team in Maine. He and I have played golf at the country club many times. His locker is next to the Governor’s.”

A potential meeting with the governor – possibly including Snow – was discussed, but it isn’t clear if it took place. The governor – who later questioned whether the MLTI program should be renewed at all – ultimately did not side with Apple in the contract negotiations.

Send questions/comments to the editors.