STONINGTON — Charlie Scott, the last ferryman who shuttled locals and from-aways on his scow between Deer Isle and Sedgwick, warned islanders about the perils of progress.

If you build a bridge between Deer Isle and the mainland, he told them, you’ll forever change the character of the island.

“Go ahead and throw it all away, boys, sell it for a wallet full of cash,” Scott’s character sings in a new musical on stage this week in the Deer Isle community of Stonington. “Sell it and explain it to your grandkids how you turned our gorgeous island into trash.”

The musical, “The Last Ferryman,” was commissioned by Opera House Arts at the Stonington Opera House. Written by Brooklin composer Paul Sullivan, the musical celebrates the 75th anniversary of the opening of the Deer Isle Bridge. Noted for its arching design and terror-inducing grade, the suspension bridge opened in 1939.

For better or worse, the island hasn’t been the same since.

As with many things that pass as progress in Maine, the bridge came at a cost. It brought tourism to the island and accommodated our growing love affair with the automobile, but gave self-sufficient islanders the convenience, or crutch, of looking inland for jobs and commerce.

It put the ferry service out of business – indeed, the ferryman Scott died two weeks after the bridge opened, ending a family tradition that spanned a century – but made it easier to transport Stonington’s valuable granite.

The bridge was controversial when it opened, dividing islanders with sharp opinions. Many bemoaned the slowness and unreliability of Scott’s ferry service. Others worried about the island’s inevitable loss of character. The majestic green span remains something of a talking point today.

Islanders have embraced the bridge and the conveniences it brings, but when Opera House Arts hosted a community forum to discuss the project, nary a single longtime resident said anything positive about the bridge, said Opera House Arts executive director Linda Nelson.

“We heard about everything that people don’t like about the bridge,” Nelson said. “But nobody talked about what they liked about it.”

On the other hand, when the arts group convinced the state Department of Transportation to close to bridge for one hour in June, more than 1,500 people showed up to walk across the bridge, which towers nearly 100 feet over Eggemoggin Reach.

“The Last Ferryman” tells the bridge story with historical figures and fictional characters. It illuminates a key cultural moment for one of Maine’s loveliest islands, and does so within the framework of a fully staged musical that features a cast of New York actors and community members, a three-piece band anchored by Sullivan and choreography by the Portland-based dance artists Gwyneth Jones and Gretchen Berg.

With a tone that wavers between Yankee stubborn and aristocratic snobbery, “The Last Ferryman” captures the conflict inherent in progress on the Maine coast. It celebrates the aesthetic and architectural wonder of the bridge while giving poignant voice to what’s lost when an island attaches itself to the mainland and gives in to the headlong momentum of change.

Underlying that conflict is the friction between those who grew up and make their living on the island, where life is never easy and “wind is always pushing at your door,” and the summer rusticators, who show up only for the good weather with their cars packed bumper to bumper, pockets full of cash and fancy yachts.

“I hope somebody writes it down, and takes some pictures too,” Scott sings in “Ferryman’s Farewell,” the musical’s penultimate song. “The way we used to live here, the things we used to do.It was quite a life we led, before the bridge came through.”

ORIGINAL WORK A PRIORITY

The two-hour musical represents a major effort for Opera House Arts, which has made original work a priority during the 15 years it has presented arts programming at the century-old opera house.

It will spend about $90,000 on the musical, much of which is being raised within the community. Opera House Arts also received several grants to develop the musical, from the Maine Community Foundation, Quimby Family Foundation and Maine Arts Commission. The organization’s overall annual budget is about $750,000.

“We’re always looking for community dialogue,” said director Judith Jerome, who conceived the show with Nelson. “One of the guiding principles for us since the beginning has been this desire to be in dialogue with the community. It’s not that these subjects are hard to find. They turn up all the time.”

Said Nelson, “If we don’t invest in creating new performance, are we going to do ‘Les Miz’ all our life?”

The roots of this show go back to Opera House Arts’ first original effort, “The Singing Bridge,” which was commissioned in 2002 and debuted in 2005. It told the story of another bridge, connecting Hancock and Sullivan.

In 2010, Opera House Arts created a musical version of Robert McCloskey’s children’s book “Burt Dow, Deep Water Man.” McCloskey lived in Stonington.

“The Last Ferryman” completes the trilogy of Down East musicals.

The specific idea stemmed from a conversation Nelson had with composer Rob Kapilow, who is a friend of Sullivan’s and was in town two years ago for a musical collaboration with Sullivan. Kapilow mentioned offhand that he had written a symphony celebrating the 75th anniversary of the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge connecting San Francisco and Oakland.

Nelson knew the anniversary of the Deer Isle Bridge was approaching, and asked Sullivan if he would write a score. At the time, she and Jerome had nothing beyond a concept, but knew the subject lent itself to something dramatic.

Sullivan loved the idea.

The bridge has captivated him for many years. Sullivan, who won a Grammy Award for his work with the Paul Winter Consort, first crossed the bridge in 1976, when he was in college. He had never been to Maine when his jazz band accepted a gig at Isle au Haut. They drove to Deer Isle in the middle of the night to catch a morning ferry and arrived at the bridge at daybreak.

“I was like most people,” Sullivan said. “I really wished I could see the other side of the bridge. You keep going up and you don’t know if you’re going to come down.”

Engineer David Steinman designed the bridge with 85 feet of clearance to accommodate the large boats that sail Eggemoggin Reach. With a grade of 6.5 percent, the bridge has a distinctive but frightening arch in the middle.

Sullivan has made his home in nearby Brooklin for more than 25 years and has crossed the bridge hundreds of times. He no longer fears it, but he still marvels at its beauty.

TRADITIONAL BROADWAY STYLE

He wrote the music and lyrics in a traditional Broadway style, with many ensemble numbers and a few ballads. There are hints of gospel, folk, jazz and what Sullivan described as “Gilbert and Sullivan pastiches. I used the whole toolbox for this one.”

He sees Charlie Scott as a heroic figure. Scott resisted change and had the island’s best interests at heart, and he held firm to his traditional beliefs and values. That he died so soon after the bridge opened imbued this story with tragedy, Sullivan said.

With Scott as his lead, Sullivan created a secondary character, Lucia, to represent the other side of the story. A fictional character, Lucia is a native islander and the daughter of an Italian immigrant, who came to Stonington to work in the quarries. An advocate for change, she firms up her decision to support construction of the bridge when Scott refuses to cross the reach during a storm after her daughter takes ill and requires medical attention.

“If your old ways mean the death of my daughter,” Lucia sings in “Look Me in the Eye,” “then you and your old ways can all burn in Hell!”

Among the other characters is Frank McGuire, a real-life businessman who also lobbied for the bridge. McGuire owned a granite quarry and saw the bridge as a way to improve his business. He died before it was completed, and the bridge is named in his honor.

“We gotta build this bridge, we gotta get ‘er done,” McGuire sings in one of the show’s most robust numbers, which features a number of older local men, who comprise the Lions Club. “We gotta hook her up so that the trucks can run.”

Sullivan enjoyed working on this project because it’s so relevant to local people. Descendants of the real-life characters in the musical live in the community, and Scott’s Landing, where Scott kept his scow, is accessible on the Deer Isle side of the bridge. “You drive by it every time you cross the bridge,” the composer said.

Nelson and Jerome worked closely with the Deer Isle-Stonington Historical Society. They hired playwright and University of Maine at Farmington professor Linda Britt to help research the story. Britt wrote the book for the musical.

Much of the material is factually correct. Several lyrics and sections of dialogue were taken from newspaper accounts, including the dedication ceremony attended by Maine Governor Lewis O. Barrows.

As well, Opera House Arts worked with students on a year-long educational project about the bridge.

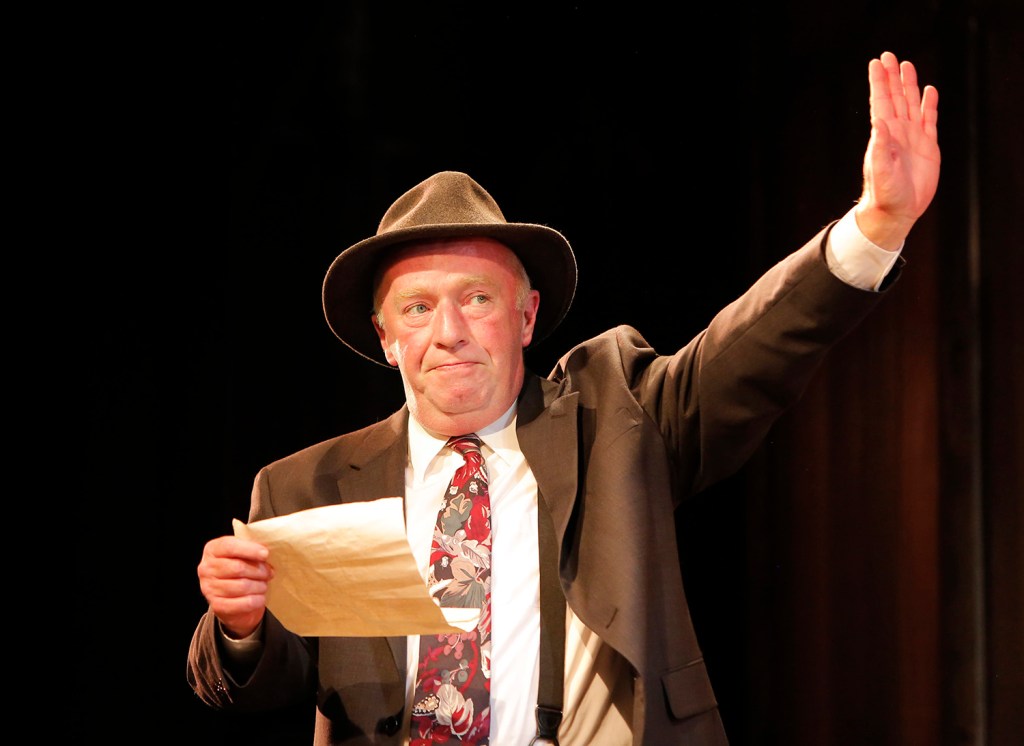

Professional actors collaborated with community members on the musical. Opera House Arts auditioned in Boston for the leads and brought in a quartet of professionals from New York and Boston: Jason Martin, who plays Charlie Scott; Emily Hecht, who plays Lucia; Paul Farwell, for the role of Frank McGuire; and Donata Cucinotta as McGuire’s wife, Annie.

The rest of the cast is rounded out by locals, including high school student Marvin Merritt IV, an acting intern at the theater. He plays Sammy Knight, the adopted son of Charlie Scott.

Merritt, who lives in Deer Isle, knew the backdrop of the bridge story before rehearsals began. Like many islanders today, he knew nothing of the controversy that accompanied the construction of the bridge. He has always taken it for granted.

“I hope community members come to see the show and hear the story,” he said. “This is our story. No one can tell it better than we can.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.