In John Heliker’s 1985 painting, “Clamdigger with Dog,” a man facing to the right looks over his right shoulder toward a black dog sitting behind him so that his face points at us. Behind him, below soft purple hills in the distance, a thick ribbon of cerulean water sets the straight horizon line at its far shore. A tall boxy red building looms on the right of the composition, turning back the left-to-right flow of the man, the water and the dog to create a surprisingly energized circuit. But the narrative doesn’t quite dominate: Two-thirds of the image is sky which, despite the clouds, refuses to be gray. It’s a Baroque dance of swirling blues and whites. It is impasto. It is strokes of color. It is the triumph of painting.

If it weren’t for the prosaic Maine scene below it, the sky could be from the Italian paintings of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo and Francesco Guardi that Heliker so often visited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

But figures are cues to most narratives, so we can’t help but come back to our clamdigger. And, whereas painters usually focus on faces and hands to describe their figures, Heliker has backed off these key points. The barely legible face is too immaterial to reveal any psychology or narrative. What does stand out about the figure, however, is how he is painted. Heliker’s drawing with the brush appears as short and clear black staccato strokes. They are decisive marks despite being reworked: The left shoulder was taken out and the upper arm dropped even though the forearm wasn’t moved; and the lines for the right arm have been similarly adjusted to add weight and dimensionality. Heliker makes no effort to hide these changes, giving the impression he wants us to follow his thought process.

We come to realize the clam basket needed to be set at its strange, jutting angle to counter the otherwise too-strong gaze line from the dog’s nose to the figure. That we can see the mountains behind the red building reveals the building was brought in late as a compositional solution. Reworked patches also indicate the man was originally facing to the right and wearing a bigger hat.

While painting fans have been fascinated for centuries by “pentimenti” (traces of painted-over changes), it was only about 100 years ago that such changes became part and parcel of the content of the work.

With its obviously reworked solid lines, Heliker’s drawing with the brush borrows from Cubism, but his compositional approach draws from Henri Matisse, particularly his penchant for leaving out specifics and making figures no more important than any other structural element. Whatever sources his inspiration channeled when Heliker painted and repainted the canvas, it’s hard not to see Matisse, Pablo Picasso and their shared inspiration, Paul Cézanne, in “Clamdigger with Dog.”

Heliker, who died in 2000 at age 91, might have been the best and brainiest Maine painter who has not yet been fully discovered by the Maine audience. “John Heliker: Paintings from the Cranberry Island Years” at the Courthouse Gallery is a show that makes a compelling case for Mainers to take notice.

Heliker was born in New York and taught at Columbia University for many years, but he came to think of his sea captain’s house on Great Cranberry Island both as his personal and artistic home.

Heliker’s Maine work features startlingly sophisticated mark-making with an unexpectedly light touch. It removes the elements of color from the brilliant staccato strokes so that they inform – but don’t rely on – each other. But while his work can be categorized as coastal Maine painting, it is undoubtedly engaged more with the culture of painting than with description or local storytelling. The result, oddly, is a sort of cultural classicism in local color – a combination that does much to elevate both the art history of Maine and Heliker’s place within it.

Heliker was no minor painter. He had a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1968. He won a Prix de Rome and a Guggenheim, among many other prestigious awards. His works are owned by the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney and dozens of the most significant museums across America. But like so many great Maine artists, he worked here but then showed his work in New York. (Heliker had 18 solo shows at Kraushaar Gallery between 1945 and 1995.)

The 20 works on view at the Courthouse Gallery range from sizable figure scenes to smaller landscapes, intimate Nabi-like interiors with what appear to be Odilon Redon-inspired floral bouquets and even some exquisite drawings. (The quality of his drawings begs for a museum show.)

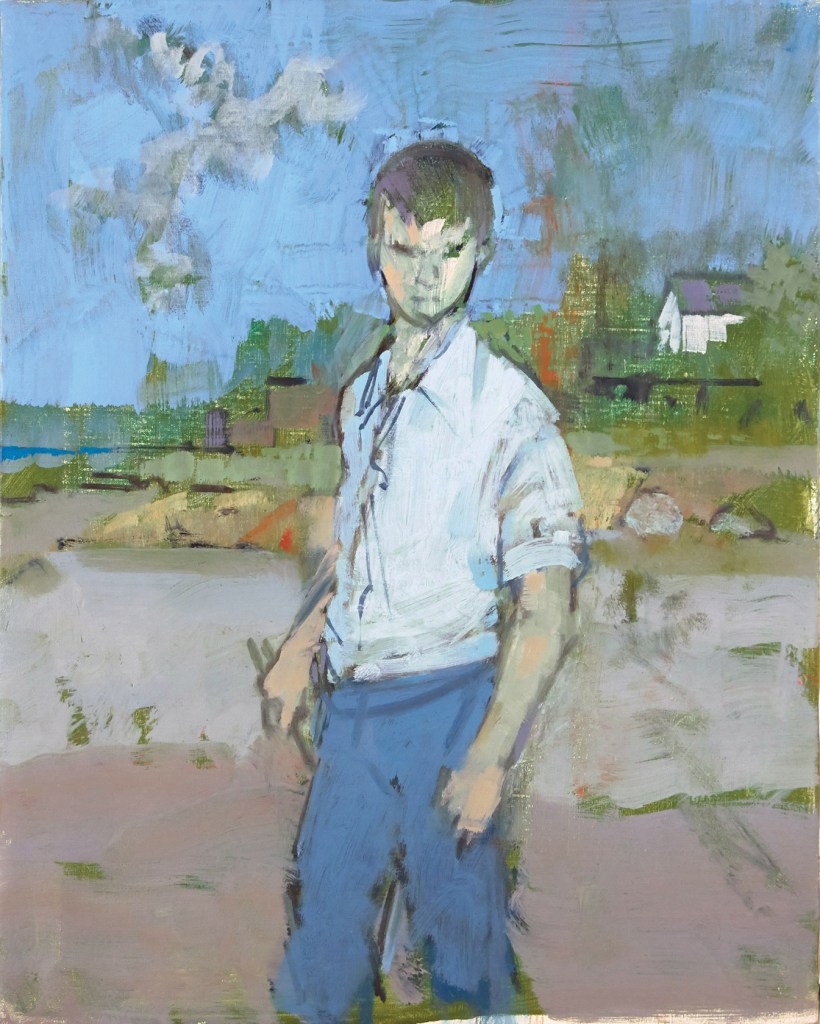

“Study of a Boy Shucking Clams” is a small but particularly revealing canvas. While it connects Heliker directly with the structural draftsmanship of Cézanne and Matisse, it is a testament to Heliker’s dedication to open form. Whereas Cézanne’s famous male figure “The Bather” (1885-87) is a clear precedent for Heliker’s “Boy,” Cézanne’s closed drawing shapes cut the figure off completely from its background. Heliker’s figure is constructed by lines that imply shapes rather than closing them in.

Heliker’s colors can therefore flow more freely into each other, allowing him more flexibility in relating the figure to the ground. Despite their improvised appearance, the black-lined, open-form drawing in Heliker’s paintings is actually the result of a rigorous process of composition completely at odds with the spontaneous chaos of Abstract Expressionism. The multiple lines echo Matisse (and to a large extent, Alberto Giacometti) not only in look, but in their serious search for the proper shape, form and structure.

Heliker generally worked in the studio from memory. This allowed him to stay closer to his sensibilities and painterly inspirations, and it keeps his art focused on painting rather than the description of specific scenes. This means that any changes we see are not in the service of accuracy but of good painting.

These images have the look of Cranberry Island but their standards are those of art history, which makes them more universal and might explain their broader audience. Heliker’s New York friends were composers and artists, including Arshile Gorky, John Cage and Philip Guston, and yet his artistic soul remained in Maine. It’s time that Maine claimed Heliker as one of our very best and brightest.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. Contact him at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.