While the previous suite of shows at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art was anchored by a powerful presentation of Jon Imber in the main gallery, the other three shows were each impressive as well – most notably, Shoshannah White’s photographic works.

One of the many reasons White continues to impress me is that she refers to encaustic-covered photos as “encaustic photos” instead of some variant, such as “encaustic on panel.” This was an important issue in the Seattle area when I was a curator and art dealer there, because encaustic was hip, hot and often misleadingly presented. (Encaustic is a painting medium that combines beeswax and resin and has hardly changed in the past 2,000 years). This mattered because artists would cover photographs with encaustic and the viewers (and collectors) would often be misled into thinking what they were seeing was encaustic painting.

As part of this discussion, in 2000 I published a piece called “The Cultural Status of Painting” in which I argued that painting was “appropriately humbling itself to the level of craft.” I stand by that – particularly regarding material-oriented abstraction like the paintings by Betsy Eby now on view at CMCA. Eby was one of the many Seattle artists I was talking about, but her work even then firmly espoused the decorative and craft-friendly qualities that have been strong and healthy threads within American painting.

In Seattle, where encaustic was all the rage, it was easier to see the painterly content of Eby’s work. At CMCA, unfortunately, the presentation devolves a bit into the “Look – encaustic!” approach I have complained about in exhibitions of works dedicated to the medium. The wound is self-inflicted: Eby presents an eight-minute film about herself that practically forces the viewer to see her as a craft artist by dwelling on the subject of technique.

To conflate technique with content is what I call “the craft mistake.” As a longtime fan of Maine abstraction – and Eby’s painting – this feels like a frustrating missed opportunity.

It’s unfortunate that it becomes too easy to overlook Eby’s content. The CMCA’s installation is elegant because it turns on another hip (and troubled) subject: Ekphrasis, or art in one medium about another, like a poem about a Grecian urn or, in this case, paintings about music.

With titles like “First Variation on a Dvorak Tone Poem,” it’s clear Eby wants the viewer to see her work as paintings about music. It’s a troubling topic, however, since it requires the viewer to be a critic of both music and art. The result is disappointing: The image of the music appears as a single narrative strand, a butterfly fluttering across the painterly space, whereas Dvorak plays with phrases, inverting, echoing and twisting them to tease our memories in real time.

Eby is an accomplished pianist (as she tells us in her slick catalog and video and proves with a nicely restrained performance of “In a Landscape” by John Cage), but this too harkens back to the unresolved craft-versus-art question: Is playing an instrumental part as written by a composer closer to artistry or craft? (As a musician and craft fan, I think this is an interesting but easy question.)

In terms of the public audience, I think the response to Eby’s show will be mixed. If you are seeking beauty and serenity or exquisite craftsmanship, you find it. But if you are allergic to pretension, don’t forget the Benadryl.

The other three shows on view at CMCA are all excellent and exciting.

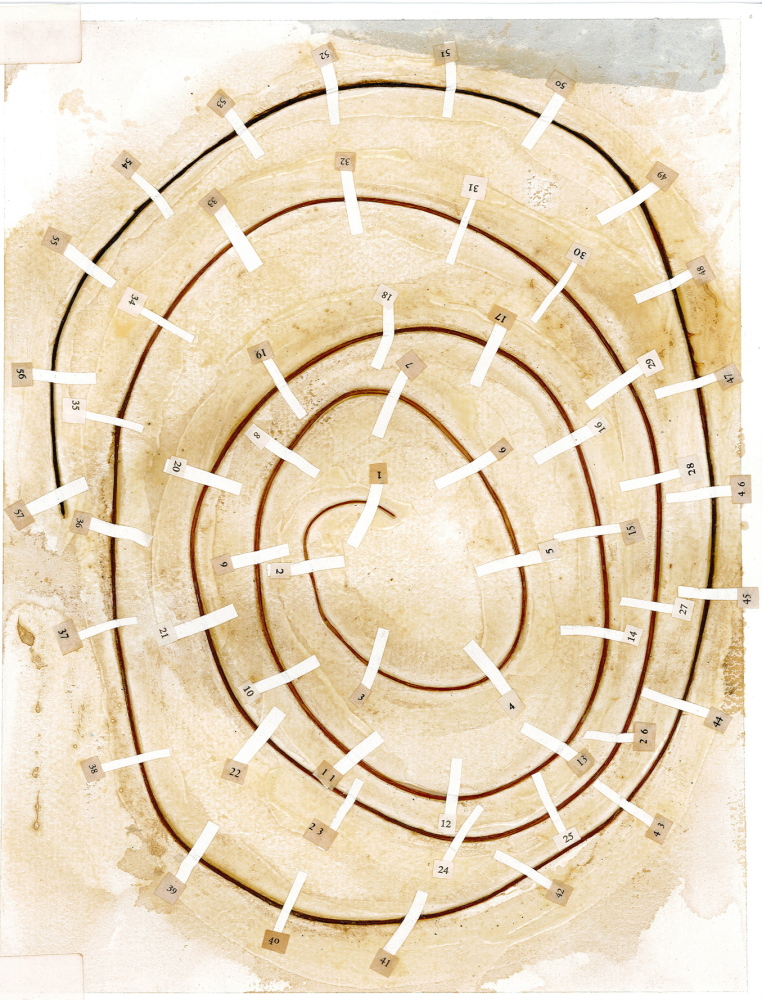

Ron Leax’s mixed media works don’t just look like scientific musings, they get smarter, wittier and more sophisticated the closer you look and the more you think about them. They have a loose, mad-scientist flavor to them that might keep some viewers away, but if you give them a moment, they pay off in spades.

Tom Burckhardt’s exhibition, “Recent Work,” is a toothy-grinned celebration of abstraction spread thick with conceptual content. While what first strikes you are Burckhardt’s highly saturated shapes in chewy retro flavors, the artist offers up real depth with his eye-popping formal vocabulary and propensity for complex compositions of interwoven tones.

Burckhardt’s backwall installation, “173 Elements of a Painting,” features 173 repurposed book pages, each containing a funky shape solidly painted in oil. It’s a great work that at once addresses issues of creativity, complexity, artistry, technique, construction and – with twistedly ironical brilliance – deconstruction.

Moreover, Burckhardt’s seemingly loose canvases are not canvases at all but repetitions of the same fake cast in plastic resin. It’s like a conceptual maraschino cherry topping a Wayne Thiebaud-painted sundae.

The most exciting work at CMCA, however, is the painting of Elizabeth Fox. Smart, savvy and slick, Fox’s exquisitely painted small narrative pictures first appear aloof and theatrical but quickly unleash a tsunami of quirky details that washes back and forth between cultural commentary and charming personal wackiness.

Fox’s paintings ostensibly play off television scenes, but with a heavy dose of pictorial wit carried easily by her New Yorker-cartoon style. In “The Drop,” we see a cross-sectional view of a money bag left in an ice fishing shack amongst three meandering figures in jeans and black jackets. The fashion-plate vanity of the model figure on the left, however, becomes insidiously – and inescapably – hilarious.

We see Fox’s women in transparent skirts revealing the precise shape of their butts and it leaves us to wonder if they are self-conscious or advertising – or if, among other options, Fox just happens to have a thing for butts. This is the main subject of a blush-worthy painting of construction workers and it pushes a scene of a “Mad Men”-esque secretary, “Apply Before Entering,” into the slipperiest bit of sexual humor I have ever seen in a painting. (It’s my favorite work anywhere of 2014.)

What makes Fox’s work so effective is the fact that some of her narrative traces are patent dead-ends while others refuse to stop for anything. Her fashion sense is real, but she employs it with a (forked) tongue-in-cheek sensibility.

Fox’s show is tiny but it has a massive impact – like an over-medicated David Lynch version of “House of Cards.”

Oh, and Fox can paint.

The underlying message of this season of shows at CMCA conveys the idea that contemporary Maine painting is loaded with conceptual heft and that it is now mature enough to leave behind the ongoing Oedipal battle with coastal painting.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.