This year marks L & P Bisson and Sons’ 85th year in business, but there is no banner anywhere to be found in or around their rural storefront in Topsham trumpeting that milestone of family farming. Nor is there a sign declaring that Bisson’s bacon beats all or that once you’ve had their hamburger, you want no other.

History confirms the anniversary and their loyal customers would attest to the truth of the last two, but the Bissons are not by nature self-promoters. They scarcely advertise (once a year in the Coastal Journal, at Topsham Fair time). At a time when the Maine agricultural brand is red hot and many in their position would try to capitalize on it to, say, sell that bacon for $8 a pound in Boston, the Bissons have continued to sell their meat, dairy and value-added products from one location only: 112 Meadow Road in Topsham.

There is a saying that speaks to a popular 21st century philosophy: Go Big or Go Home. The Bissons have not gone big and they never left home. Theirs is a story of quiet sustainability – making careful choices, putting in long hours and building community – but above all, it is about family. One look at the walls of their shop, plastered with photographs of the now five generations working this farm, is testament to that.

THE OUTSIDE

As the man behind the smokehouse that makes that bacon, Arthur Bisson, 61, the namesake of the first Bisson to farm this land, is nominated by his siblings as the family spokesman, although he’s not entirely comfortable with that designation. Nonetheless, it’s he who cautiously welcomes a reporter into the closet-sized office, offers a cup of coffee and starts talking about the family business.

The first time Arthur refers to “the outside” one assumes he’s talking about what’s literally outside the door of the meat shop. Five hundred acres of gently rolling farmland, populated by anywhere from 400 to 500 head of beef cattle or dairy cows, depending on the time of year, and kept green and rich by the nearby Cathance River.

But in the world of L & P Bisson, there is working for the family business and then there is everything else, in short: “outside.”

“I’ve never worked on the outside,” says David, Arthur’s only son. He’s 37 and started at the shop somewhere around age 8. Or maybe he was 5.

“I just remember standing on a chair to scrub the smoke stakes,” David says, referring to the metal rods used to hang the meat in the smokehouse.

With so many Bissons about the place, start dates get fuzzy. There are 14 people on L & P Bisson’s payroll, and almost all are family. (The business name derives from Arthur’s parents’ initials, his mother, Lorraine, who died last December at 93 and was better known as Mémère, and his father, Paul, who died in 1991, just after his 74th birthday). And that doesn’t count the family members who show up to work during the busy seasons (holidays, for one) or pull a shift on a Saturday when 300 customers might well pass through before the doors close at 4 p.m.

WASTE NOT

Customers of the meat shop know about the bacon and the smoked pork chops and the chicken pot pies (made from Mémère’s recipe and filled not with chicken and vegetables that picky eaters might balk at but rather with chicken and stuffing; she had 11 children to feed and perhaps took the path of least resistance).

But beyond flavor, beyond taste, the key to Bisson’s success may well be a diversification you’d never guess at standing in the shop, from the state-inspected slaughterhouse that serves many other area farmers to the sawdust business the family started after local mills stopped wanting to sell to the public. There is even a darkened barn where the cow hides are preserved with salt and left to wait for the leather producer from out of state who comes to pick them up once or twice a year.

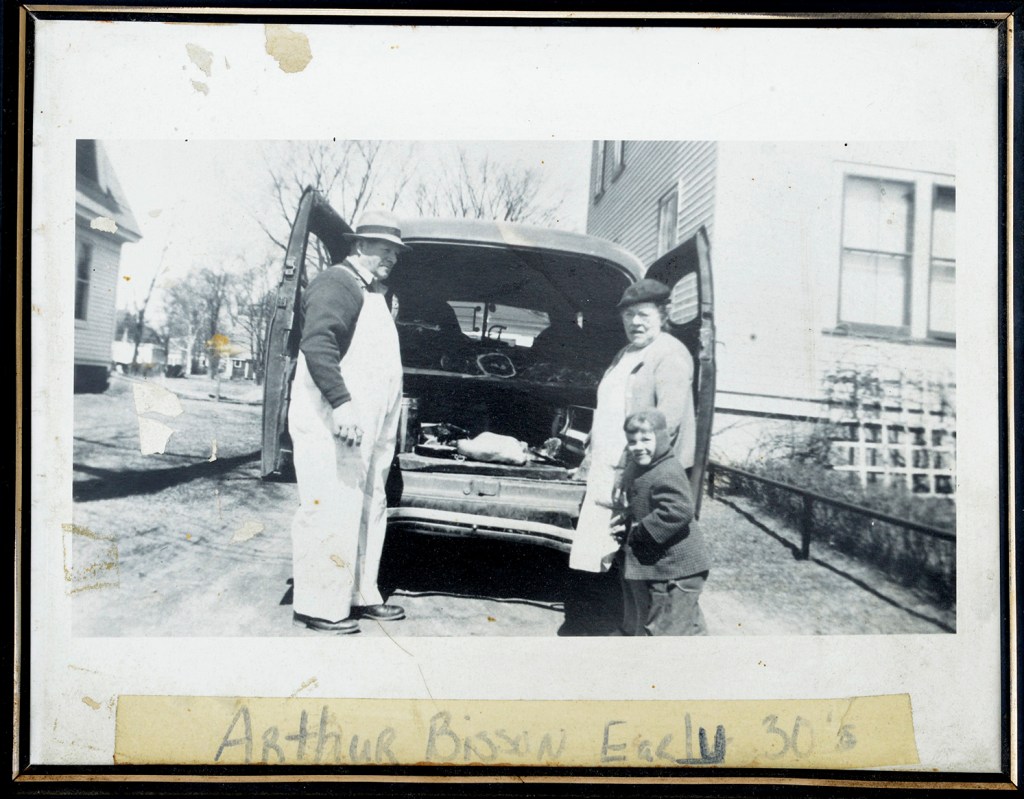

Just out the back door is the milk house. It’s afternoon and most of the dairy cows are in the barn, lined up 50 to a side. The first Bisson to farm this land was Arthur’s grandfather, also Arthur, who was born in 1892 in Quebec. He emigrated from Pointe-Du-Lac to Brunswick around 1912, got a job as a baker at Helie’s Bakery on Mill Street and married a local woman named Odile. In 1929, he bought Topsham’s Beechwood Dairy. He continued to work at Helie’s while his wife and children, including Paul, sold milk under the Beechwood label, and eventually meat. Paul took over the family business in 1958. The original patriarch stayed on the land, keeping an eye on everything his son – and his son’s five sons and six daughters – were up to.

“He was a nice guy, but he was a hard man to please,” Arthur Bisson says of his grandfather. “If we was doing something wrong, oh geez, he’d come out and get after us.” And in French – the first Arthur Bisson never learned English.

Paul’s ambitions for the farm exceeded his father’s. He dreamed of a barn spacious enough to hook up 100 cows at once and of having a real retail shop where the family could sell meat and milk (in the early days, they delivered by truck and sold out the “back door”).

“My mother repeated this over and over again,” Arthur says. “When Dad was peddling milk and he had arthritis in his hands, he’d say ‘Someday I’m going to have a store up here and people are going to come up and buy the meat and the milk.'”

“My mother said, ‘You know, I just can’t visualize people coming up here to get it,'” he added.

BUILD IT, THEY WILL COME

But Paul Bisson fulfilled both dreams and changed the way his wife saw things. Paul’s 100-head barn went up just before his youngest son, Andy, was born and that same decade he bought an old shop from someone in Gardiner and hauled the building to Topsham. There have been some additions, but that building, bought on the cheap, is still the core of the shop that operates today. “He tried to be self-sustained,” Arthur says of his father. “If we didn’t have money for something, we didn’t buy it.”

Today’s dairy, managed by Andy, is a revitalized version of the one that Paul Bisson so cherished. Paul had closed it in 1969 and sold the cows, but never the equipment. (” ‘Maybe the boys will want to do it again,’ ” Arthur remembers him saying. ” ‘And it will be there.’ Which it was.”) In the meantime, Arthur left for the “outside,” joining the military. “This is what I thought,” he says, his soft voice getting jagged. “I didn’t think he needed me anymore.”

Arthur would get letters from his father during his service – he never went overseas – telling him about things he’d done on the farm, including getting a few new cows and doing some slaughtering. “It takes a while to sink in but I’m thinking, he wants me to come back.”

Back problems derailed Arthur’s military career and he came home to a father eager to try new things on the farm. They built a smokehouse. They experimented. They taught themselves. “‘We’re either going to go broke or we’re going to make it,'” Paul Bisson told his son. They started building a reputation. That smokehouse burned. They built another.

NEVER FORGOTTEN

When Paul died of a heart attack, the family was at a loss. “We didn’t know what we was going to do,” Arthur says. “He worked with us every day. Some days we’d come in and say, ‘Dad, we’re going to do this,’ and he’d say, ‘No, we’re going to do this.’ He called the shots every day. So when he passed away we was a couple of months just going around in circles.”

Of Lorraine and Paul’s 11 children, today four of their sons (Arthur, Raymond, Bob and Andy) and one daughter, Priscille Pollock, are owners. (The name says & Sons, but Priscille lets that roll off her back: “I think my dad forgot he had all these girls.”) They proceeded with caution, numbed by grief but intent on taking care of their mother, who until she was 90, still came into the shop to help make the meat pies. They’d never been rich, but they’d always, as Arthur puts it, “stayed our head above water.”

That goal persists and is the message Arthur refers to throughout his tour. A group of heifers stand in a corral near the milk house, and he explains that at least some of them will be sold to dealers. They recently sent a group off to Greece and once shipped Bisson-raised dairy cows to Iran. “We have to do a number of things to survive,” he says. “That is just one of them.”

There isn’t a day that goes by, Arthur says, when he’s not thinking about how his father ran the business. “I still feel like I’m working for him,” he says.

SMALL CHANGES

Gradually though, they started to make changes. They bought a dough roller for the pies (Mémère refused to use it). They built a new milk house so that they could pass state inspection to sell raw milk – that’s Andy’s passion. They run the place with true Yankee thrift; Arthur points to the butter machine that Andy taught himself how to maintain – good thing too, since the mechanic from Ohio who used to service it stopped making rounds in Maine – and says “that thing must be 50 years old.” A square tank filled with raw milk sits nearby, ready to be picked up by Hahn’s End of Phippsburg, which uses Bisson milk to make its cheese.

The sign that hangs inside the shop, wooden and brown, the letters hacked out with a knife, is the same one their father made in the 1980s, rough hewn in that Wild West way. But the cash register now includes a credit and debit card machine; not Paul Bisson style. He would, however, have approved of the steady stream of customers lined up for the Bisson family farm’s products. And of the solution his son Arthur came up with when their old, galvanized steel smokehouse wasn’t passing muster with state inspectors: Arthur drove to Illinois to buy himself a state of the art smokehouse at a bargain rate.

It looks like a bank vault, sitting in a big room behind the retail shop. Grinning broadly, Arthur switches on the light and swings open the stainless steel door. The smokehouse is one of the biggest expenditures the family ever made. Its walls are pristine (the old one never looked clean, even when it was, Arthur says). He found it used, paid $25,000 for it and brought it back to Topsham on a truck with a family friend in 1999. It’s his baby and he’s proud of it. “I can do 800 pounds of meat in there,” he says. He smokes every Monday, when the shop is closed and a state inspector can be on premises to check his work. The Bissons do bacon in such bulk that Arthur has to buy pigs from Canada to meet the demand.

Four or five years ago, they rigged up the smokehouse with equipment so that all the timing can be handled from computers elsewhere (there’s an app for that). “I take my laptop home to Bowdoin and watch what it is doing from there,” Arthur says with satisfaction. Truth be told though, much of the time he’s monitoring the smoking from the apartment his father built for him over the shop; it’s hard to get a Bisson too far from the farm.

AHEAD ON MEADOW ROAD

That’s not to say everyone stays “inside.” Priscille is the only one of the six “girls” to work full time at the farm. One of the brothers, Roger, has a bad back (Arthur has one, too) and doesn’t work in the shop. And there are a few employees from “outside” who have made it into the fold. Sort of. “I’m the outcast,” jokes Samantha Coffin, 22, who works in the front shop while her husband works on the farm with Andy. “I usually meet a new Bisson every day.”

With the craze for local products, the whole family knows they could sell that bacon of Arthur’s or those pies from Mémère’s recipes far and wide. Someone from NASA once bought enough jerky for his whole department and took it back to Florida. New Yorkers and Bostonians in the know shop in bulk, driving South with coolers loaded with Bisson’s meat. But there are obstacles, some practical, some emotional.

“We have so many products that we make here,” David Bisson says. “And much of it is hands on. We don’t have any more room.”

Keeping their heads above water was crucial in those years after they lost their father. The Bissons have worked their way to a “fair living,” says Priscille, who keeps the books. “It took us a long time before we could get ahead a little.”

They’re protective of that margin. “We don’t buy new,” she says. “We have got a couple of loans, equipment Andy wanted. You make do. We don’t want to get into trouble.”

It’s unclear who, if anyone, in the next generation will take over the farm and the hours it takes to run. Priscille just turned 65. Arthur is almost 62, and he’d like to retire, “to live a little.” Andy, who starts his day with the cows at 2:30 a.m. and often doesn’t end it until 8 p.m., may not have the time to reflect on what comes next. Priscille has a grandson who is so passionate about the farm that he believes he needs to be there every day. But for now, no plans are in place, except continuing to work the way Paul Bisson taught them to.

And they are still coping with the fresh loss of their matriarch, whom they looked after with fierce devotion. “My father always told us to take care of my mother,” Andy Bisson says. The size of a lumberjack, he descends from his tractor to shake hands – his grip could be crushing, instead it is as warm as the sun – and tell a few stories. Like the time his mother asked them to extend her porch so she could sit on it and watch them at work, especially him, her baby Andy, who is often still driving his tractor in the twilight. The family needed a variance to change the porch and went en masse to Topsham town officials to ask for it. It was granted, but as Andy put it, “We were going to do it anyway.” She died last Dec. 19 on that porch. Andy says she told her children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren, “If it wasn’t for you kids I would have left a long time ago.”

Her great-granddaughter Chelsey, 21, who works in the shop, contemplates a future “outside.” She says she’d like to be a social worker, to help troubled kids. But who knows? “I don’t know where life will take me,” she says. “For now, I’d rather work with family.”

And something else might keep her at Bisson’s; she’s just found out she’s pregnant. The sixth generation cometh.

Send questions/comments to the editors.