AUGUSTA — Perhaps you’ve never heard of them, but at one time passenger pigeons so populated the nation’s woods and skies that they generated nearly mythical tales of flocks blotting out the sun or taking hours to migrate overhead.

Their destruction, described in a new exhibit at the Maine State Museum as “probably the most famous example of mankind’s extermination of a species,” helped plant the seeds of conversation designed to keep any other species from coming to such an end.

“By 1896 — 1880, really — they’re not here. They’re gone,” said Paula Work, the museum’s curator of zoology. “Even in Maine you can see these huge numbers going to nothing, in a lifetime.”

The last known passenger pigeon, Martha, died at 1 p.m. Sept. 1, 1914, at the Cincinnati Zoological Garden. The museum display claims it’s the only instance when the precise time of the extinction of a species has been recorded. A group composed of scientists, educators and artists has launched Project Passenger Pigeon, a nationwide effort to mark the 100th anniversary of Martha’s death, with a book, a website and a film. Work said the museum, too, is using the anniversary to tell the pigeon’s story and relay the lessons learned from its demise.

“We’ve always wanted to tell more of the passenger pigeon story,” she said. “This was the perfect opportunity.”

Two well-preserved pigeons, a male and female, and a painting made in the early 1850s by an unknown student of artist John G. Cloudman, highlight the museum’s exhibit. The display lighting, designed to give the feel of daylight, help bring out the birds’ vibrant colors and striking, long tails.

“We have beautiful birds,” Work said. “I think we’re really lucky to have a male and a female and in such beautiful condition.”

NUMBERS IN THE BILLIONS?

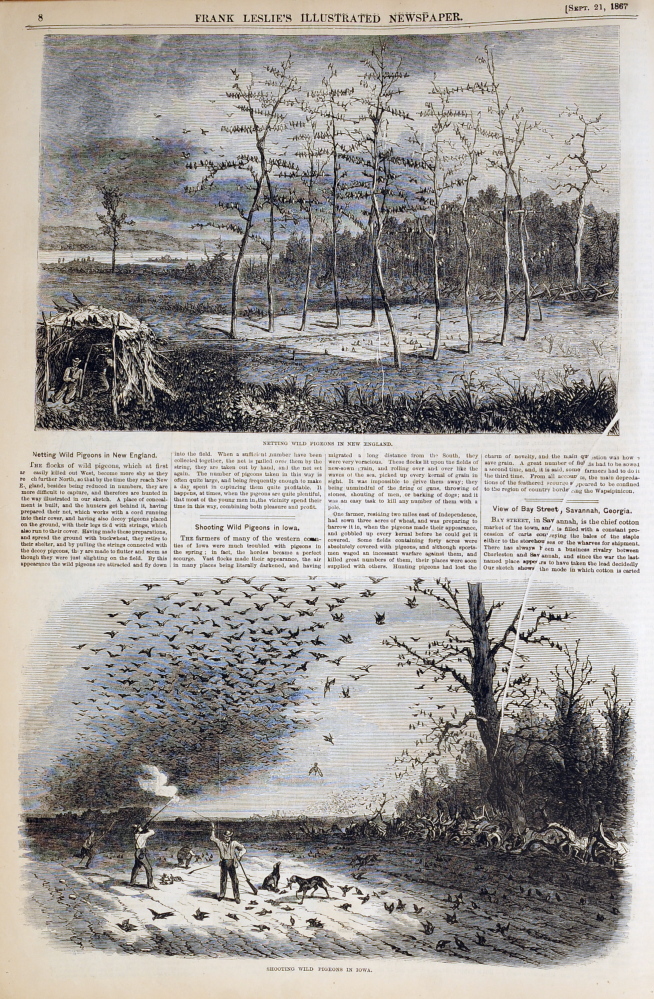

Eyewitness descriptions of passenger pigeon flocks wold defy belief if they were not so uncommonly consistent. Early European explorers describe flocks a mile wide that flew overhead for hours at a time during their migrations from the south to breeding areas in New England, New York, Ohio and the lower peninsula of Michigan. Work said their numbers may have reached the billions.

In 1605 Samuel de Champlain described “an infinite number of pigeons,” many of which Champlain and his men killed for food. A 1643 journal describes a flock of more than 10,000 that ate so much grain that the Plymouth Colony nearly starved. The next year, colonists killed the birds as an abundant source of meat.

The “History of the Town of Union,” published in 1851, says flocks “have been seen so large and long that the two ends were not in sight at the same time.”

Settlers caught a large number, but the history noted the particular prowess of Jessa Robbins, who “caught 30 dozen and ten at one haul.”

At one time the birds were so bountiful that they would be trapped only to be released to be targets of recreational shooters as they flew away.

“Pigeons were so prevalent, that’s what you shot,” Work said. Later, when the pigeons became scarce, marksmen would replace the live pigeons with clay models. The skeet used by modern shooters are still known as clay pigeons.

Work said the term “stool pigeon” also owes its origin to passenger pigeons. People used to blind the birds by sewing their eyelids shut and the birds would be released to flutter on the ground, which would call in other birds to be captured by nets.

By 1867, the great flocks had become so uncommon that the birds’ return “was considered fortunate” and caused neighbors to “turn out with shotguns to enjoy the sport of pigeon shooting, which they said was getting scarce.”

By 1897, a lone bird shot near Dexter was described as a “stray bird” and an 1898 article in the Lewiston Evening Journal quotes a reflection on the last live pigeon shot in Maine that occurred “before the wild pigeons became so scarce as they now are.”

“By 1898, we’re lamenting the pigeons’ disappearance,” Work said.

By 1909, a $300 reward for information on a nesting pair of wild passenger pigeons went unpaid.

CHEAP MEAT SOURCE

While the pigeons disappeared from Maine before they did from the rest of the country, their killing was no less relentless outside of this state. As their breeding ground disappeared because of logging, the birds were killed not only as pests who destroyed crops but especially as a ready supply of meat for America’s growing cities in the East and Midwest.

“Without the growth of the cities, there wouldn’t be a drive for cheap meat,” Work said.

By 1855, hunters shipped 300,000 pigeons per year to New York City. The telegraph, used to communicate the birds’ locations quickly, and trains, which gave hunters mobility to get to those flocks, made the pigeon harvest devastatingly effective. Hunters doubled their impact not only by going after adult birds, but also by burning and cutting down trees to get at the nests to harvest the squabs.

By 1870, there were upwards of 1,000 hunters, or pigeoners, attracted to the roosting sites by the thought of easy money. A hunt in 1878 in Michigan led to harvest of 300 tons of pigeons that were packed 55 dozen to a barrel and shipped to New York.

“By the late 1890s, only a few hundred passenger pigeons survived,” according to the museum display. “Relentless unregulated hunting, progressed year after year until any remaining isolated populations fell to levels from which recovery was impossible.”

EXTINCTION SPURS LAW CHANGE

For years the public and lawmakers sought to blame the demise of passenger pigeons on anything but hunting, Work said. When no other reasonable cause emerged, it help spur laws to protect endangered animals.

In 1900, Republican U.S. Rep. John F. Lacey of Iowa introduced a bill to protect wildlife that was a first in the nation, according to The National Audubon Society. The bill made it illegal to poach game in one state and sell it in another.

“The wild pigeon, formerly in flocks of millions, has entirely disappeared from the face of the Earth,” Lacey said. “We have given an awful exhibition of slaughter and destruction, which may serve as a warning to all mankind. Let us now give an example of wise conservation of what remains of the gifts of nature.”

Work said the general opinion was that there were too many birds to ever be destroyed by hunting. Wiping out the passenger pigeon, which at one time could darken the sun, proved that opinion wrong.

“People became aware that they were great killing machines,” Work said.

There are those who would like to use the genes of preserved passenger pigeons to bring the species back, but Work hopes the plan never is carried out. The lessons learned from the pigeon can help us navigate the future, but the birds themselves must remain in the past.

“Where would it survive in the modern world?” she asked. “I think they could genetically bring it back, but I don’t think we could bring back the species.”

For more information on the history of passenger pigeons in Maine, click here.

Craig Crosby — 621-5642

Twitter: @CraigCrosby4

Send questions/comments to the editors.