I had a conversion moment with the work of Alex Katz while teaching a class in 2001 at the Bellevue Art Museum in Washington. The docents explained Katz’s 1990 woodcut “Camp” as a night scene with three orange tents in the lower right. Since in Maine, a house on a lake – shack or mansion – is a “camp,” I knew the rectangles weren’t tents but lighted windows; and I could feel the lake behind me. It was an extraordinary composition: powerful, compelling and unique.

Considering how many times I’ve used this story to explain my newfound fondness for recent works by Katz (I always loved his early paintings), I was rather stunned to see that same composition – only with four windows and a moon rising over the trees and made in the 1950s by a different artist – on page 71 of the exquisite catalog “Bernard Langlais at the Colby Museum of Art.”

Certainly accidents happen, but Katz and Langlais had studios a floor apart in New York City at the time when Langlais was working on his painting. However you parse the improbable likeness to Langlais’ “Summer Cottage,” “Camp” implies that Langlais’ works were strong enough to exert influence.

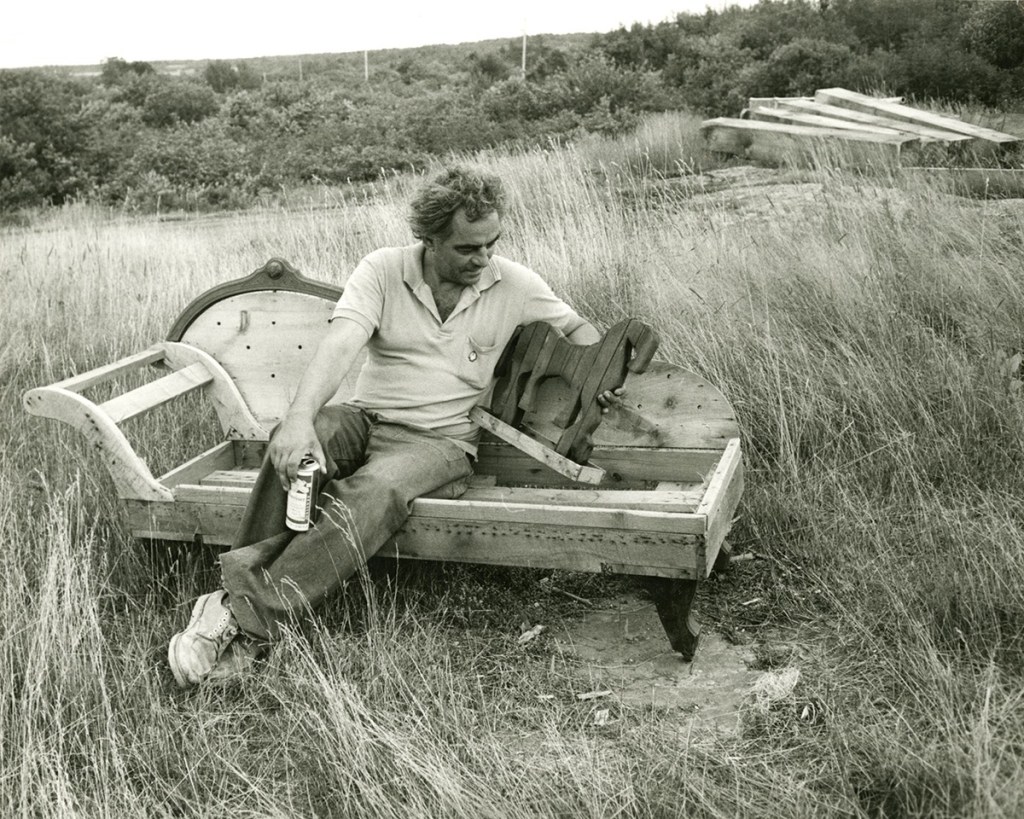

Bernard “Blackie” Langlais (1921-1977) was born in Old Town. He studied with major artists, such as Max Beckmann. He was awarded a Fulbright scholarship to study Edvard Munch in Norway. He showed at major galleries like Castelli in New York and enjoyed more than his 15 minutes of stardom. Then, surprisingly, the prodigal son returned to Maine, where his work traded in the sophisticated art world flavorings for a rough-hewn brand of sculptural primitivism.

To mark his studio in Cushing, Langlais created his first monumental work: the giant “Horse” (1966). It was masterful because it clearly emanated power but in no simple way. As a flat work, it was more painterly form than sculpture, and its heroic scale transformed the land around it into a landscape painting. It was raw, as ambitious American art was trying to be. And because its insistent mysteries felt like tribal secrets (instead of personal privacies), it seemed to contain a dangerous reserve not unlike master carpenter Epeius’ infamous Trojan horse.

Three years later, the most famous sculpture in Maine was Langlais’ 65-foot-tall Indian in Skowhegan. As a Waterville teen who frequented the Skowhegan State Fair, I remember when it went up. I was never sure if I liked it and even less sure if it was art.

In part because it doesn’t offer any simple answers, Colby’s “Bernard Langlais” – the late artist’s first retrospective – is an excellent exhibition. It is interesting and comprehensive. And it doesn’t sand the rough edges.

When Langlais’ widow, Helen, died in 2010, the works and papers remaining in the estate went to Colby. While curator Hannah Blunt spent years on the project, Helen Langlais had already expertly carved out what key works were going to the college museum. With the Kohler Foundation, Colby then disseminated other works to more than 50 Maine institutions.

The Colby show will not give you a clear understanding of Langlais the artist, but it puts beyond question his artistic and conceptual depth: Langlais was a brilliant, talented and subtle artist.

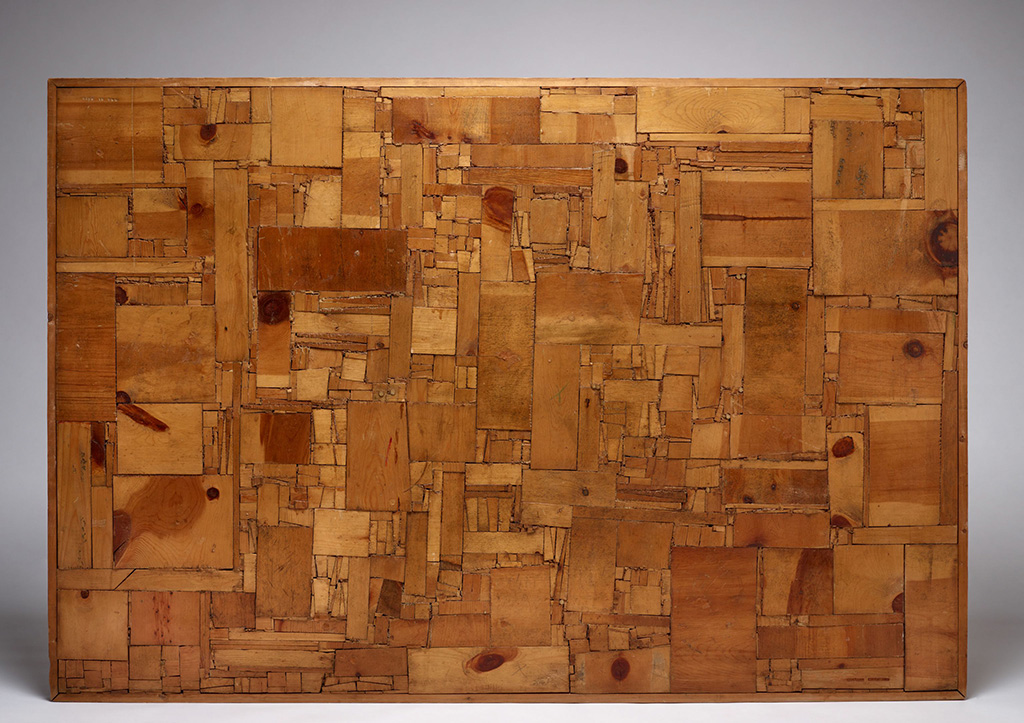

As visitors enter the museum’s excellent new lobby, they are greeted by five powerful wood assemblage paintings, all at least 6 feet tall, including several of the best works in the show: a brilliant modular grid of raw wood assemblage variations, “Pigeon Holing” (1961-1962); a reductive abstract expressionist composition, “Aged in the Wood” (1962); a giant red “4” on a navy ground, “Around Four” (1959-1962); and a tribally fearsome roaring white cyclops in a Mona Lisa pose, “Untitled (White Portrait)” (1962-1963). To punctuate and foreshadow Langlais’ stylistically radical transformation, alone to the right of the entrance is the uncomfortably severe and similarly scaled “Eagle” (1964).

To enter the exhibition, however, is to step into another world. Langlais was a strong painter and his early works are steeped in a deep and sophisticated love of painting. Munch and Beckmann, for example, aren’t merely stylistic muses but models for powerful originality.

To focus on references to other artists in Langlais’ works is to misunderstand his intentions and artistic path. He was on a quest for authenticity – something you can’t learn from other artists. All they can do is inspire you to find it for yourself.

And Langlais was inspired.

With “Made in USA” (1958), you can feel Langlais has become his own man. It is an assemblage of raw carpentry scraps crammed mosaic-like into a six-foot wide panel. In the context of contemporary painting, it was very strong. In the context of the shifting zeitgeist marked by the seminal 1961 Museum of Modern Art blockbuster exhibition, “Art of Assemblage,” Langlais was prescient: His work bridged American painting, assemblage and the aspirations of the blossoming American Craft Movement.

If you see these wood assemblage works as the maturation of Langlais’ desire to make art that was genuinely authentic, then Langlais’ ostensibly perplexing artistic shift becomes clearer. The major theme of the retrospective, after all, is the question of why Langlais left behind the kind of art world success most artists can only dream of (collectors, critics and galleries all gave him the thumbs up) to move back to Maine and make painted primitivist woodcarvings.

It’s easy to see how an Abstract Expressionism-inspired artist would need to make work that felt authentic to him. When Maine welcomed him home with open arms (his father was a Maine carpenter) and made a big deal about his work, Langlais was finally known as BERNARD LANGLAIS (his signature was big, clear and all in capitals) rather than someone in the pack being sold by some hot dealer.

Dedicated to authenticity, Langlais chose to become his own impresario.

While I cannot pretend I like the scads of crudely carved lions, it’s undeniable that the tremendously talented Langlais changed the Maine art landscape and that his late sculptures successfully achieve a raw and intentionally primitive power. Having seen the Colby show, I certainly understand Langlais’ late work much better and even enjoy its impressiveness.

Returning to Maine, Langlais came home not only to his family, but to the art of Louise Nevelson and Marsden Hartley. And now his work has come to roost at Colby. It feels right, and the old impresario could hardly have asked for a better presentation.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.