John Whalley is an artist worth watching very closely. His technique is so extraordinary that it can fool the viewer into confusing the question of how a picture is made with the question of its meaning. This is a common problem with fine craft like blown glass.

And it’s now the typical response to contemporary, high-focus painting.

While many artists hide their lack of content behind a wall of impressive technique, some of America’s greatest artists (such as Richard Estes and Andrew Wyeth) have used great technique as a vessel for deeper content.

Whalley belongs to this latter group.

Whalley made a name for himself as one of the most accomplished graphite artists in America. And while he produced drawings for “Book of Days,” none was hung in the show. Instead, the exhibition space is crammed with paintings in oil and egg tempera.

The most obvious quality of Whalley’s paintings is their stunning detail. His still lifes are so much clearer than photographs that they feel like hallucinations.

“Leatherbound,” for example, features a small tan and brown embossed leather book lying flat on a nondescript beige surface seen directly from above. A well-used old house-painting brush with long bristles and a worn wooden handle lies on top of the book. The two are bound together with similarly-wizened wound cotton cord.

It’s technically masterful: Whalley glazes with tempera like few in history ever have. Glazing is a technique championed by the Old Masters in which many thin and largely transparent layers are put down on top of each other.

Many of the strongest works in “Book of Days” are in this straight-down-view format that looks back to the American trompe l’oeil painting of John F. Peto and William Harnett. The most poetic is a blue and white Chinese teacup lovingly laid on a heavily worn cerulean “Bangor Grange Cook Book” lying on russet pine floor planks. Most notable, however, is the pair of mortality-themed oils on the same planks featuring a tall slender nineteenth-century ledger labeled “Day Book” with, first, a set of seven stones on it and then a well-traveled old-school navigational compass.

Whalley displays a few of these objects in the exhibition, including the books and teacup. In doing so, he lets us see the painterly liberties he takes in cranking up the saturation of the colors, for example. And, rather than keeping the items as secret personal symbols, he lets us share the mysteries of the objects themselves.

Several of Whalley’s tempera paintings, including a trio of pears and a still life with a yellow pear, blue grapes and a red tin, are some of the most extraordinarily glazed paintings anywhere in Maine. If you get caught up in trying to fathom the 50 or so layers of paint they required, at some point you may realize you’ve been caught in a sort of trap. It’s a very strange and wonderful Zen-like trap, but it’s a trap nonetheless.

You also get the idea that Whalley loves being caught up in that very same trap.

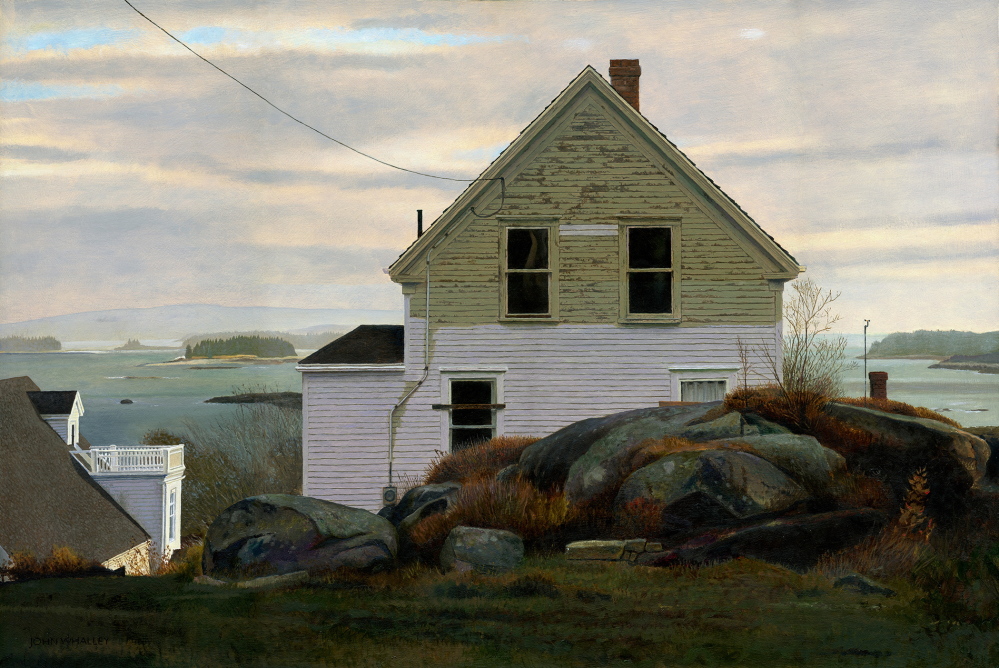

“Unfinished, Stonington” is a witty meditation from the perspective of Whalley’s patient self-awareness. (His ability to laugh at himself is very important. Paintings that have clearly taken a tremendous amount of time, effort and skill can be extremely uncomfortable if the artist is uptight or neurotic. But Whalley comes across as exuberantly patient.) It’s a seaside landscape featuring a house whose glistening whitewash only reaches halfway up the cracked and peeling coat it has come to replace. While the show’s not so deeply hidden theme of mortality might bring to mind an artist’s anxiety about the works never made after he shuffles off this mortal coil, Whalley’s sweet and selfless touch comes across more like an insightful comment about the ironic relationship between the artist and his painting: A painting, after all, is always unfinished while the artist is creating it. (Could it be that this house is somehow more alive in this state? Isn’t being alive the same as being “unfinished”?)

Landscapes are a new thing for Whalley. And they remind us that his greatest skill is observation. Not surprisingly, his mastery of light and color is superb. He paints seaside scenes as though he’s been doing it forever. But Whalley shines in the details and such scenes provide him with a different – and delicious – mode of complexity.

Whalley’s “Fisherman’s House, Rockland” features a simple mint green house at dusk. While the house is past direct light, the top three windows reflect the glowing sunset off to the right. But the painting is very subtly punctuated by the tiniest sliver of direct sunlight on the highest trees at the far left of the painting. Very quietly, a white propane tank pulls your eyes from the orangey front windows down to the back of the house where a clothesline pole points up to the exquisite bit of light.

The compositional possibilities in his unexpectedly playful landscapes seem like a newfound freedom for Whalley. So let’s hope this is not a temporary direction.

Certainly it’s unexpected to see a Whalley show with landscape paintings and no pencil drawings, but “Book of Days” makes clear that we should expect surprises from John Whalley.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.