For weeks, Maine’s marine research centers have been flooded with questions about a seeming jellyfish invasion in local waters, primarily Casco Bay. They’ve ranged from the urgent – should I let my kids go in the water, or are they going to get stung? – to expressions of longer-term fears, namely, is this the result of global warming? Ocean acidification in the warming Gulf of Maine? Proof of a hypothesis that we’re headed for an ocean ecosystem clogged by jellies, creatures that cause many beachgoers to shudder in revulsion?

Researchers across the board say they just don’t know what the cause is. It could be climate change, including warmer waters. It could be a depletion of oxygen in coastal waters because of runoff from the land, or some response to overfishing.

Or, the June bloom could be a random explosion of a species that goes as fast as it comes.

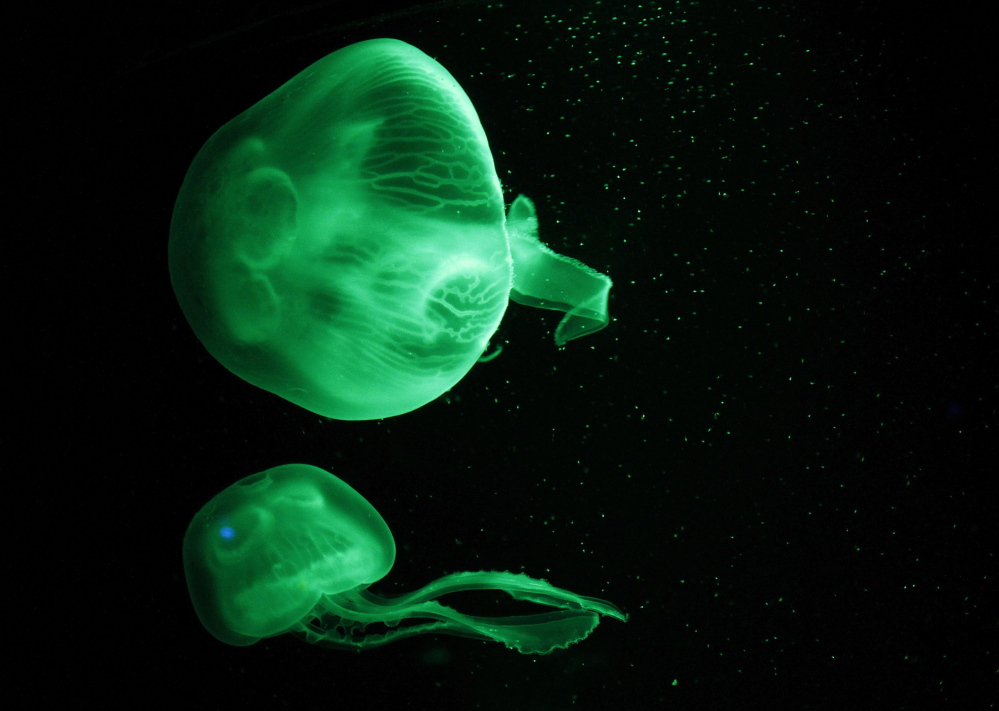

Although they move without intent, drifting on currents, jellies – the term scientists tend to use for the gelatinous zooplankton these days, rather than jellyfish – are opportunists. They take advantage of holes in the system, competing with fish for the same tiny nutrients.

The waters off Maine have three types – moon jellies, comb jellies and lion’s mane jellies. Only the lion’s mane has a sting harmful to humans.

LIMITED RESEARCH ON MAINE JELLIES

Cathy Ramsdell, executive director of the Friends of Casco Bay, said her group has been getting questions about the creatures “everywhere we go this summer.”

“It is frustrating to not be able to say anything other than speculative things about why,” she said.

That’s because no one in Maine has made a study of them. Trying to get a jelly expert on the phone is like playing a game of hot potato where you’re the potato, but all roads seem to lead to Andrew Pershing, chief scientific officer and ecosystem modeler at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute in Portland. Even he demurs.

“I am the person willing to talk about jellyfish, but it is an interesting state of affairs where I am what passes for an expert on jellyfish,” Pershing said. “I can’t think of anyone who studies them (in Maine) and we don’t really have good data on the distribution of jellyfish.”

But at least one researcher, Nick Record of the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in East Boothbay, has decided after two seasons of a noted increase in jellies that it is high time to start tracking the species in Maine. This summer he began building a library of the species spotted here and hopes to create predictive models that might tell us when to expect jelly blooms like the one that began this June.

“Then hopefully, a field program,” Record said. That’s all contingent on getting funding, because as he points out, although the public is more aware than ever about what is happening on the Maine coast – and ready to send an email or make a phone call to report it – there is less funding for such studies because of federal cutbacks in research.

SIGHTINGS LEAD TO QUESTIONS, FEARS

“It’s hard talking to scientists because none of them want to commit and none of them want to be wrong,” said Dan Devereaux, marine warden for the town of Brunswick. He believes it’s all about elevated ocean temperatures.

He started noticing jellies in the water from Simpson’s Point to the Mere Point boat launch in the second week of June. Swimmers have been calling to report them; they’re nervous about going in the water. This June bloom surprised Devereaux, who has been working on the water in the area since 1991.

“We have had jellyfish before,” he said. “But we haven’t had jellyfish where you look off the dock and all you see is jellyfish.”

“This year it was scary,” said Anne Murphy, whose family has owned a summer place in Brigham’s Cove since the late 1970s. She opted not to swim in the jelly-thickened water.

“I looked down in the water and I was like, ‘What is that?’ I have never seen so many,” Murphy said.

At Paul’s Marina on Mere Point in Brunswick, owner Judy Marsh said she didn’t think the bloom was exceptional, but it seemed to linger longer than it usually does. She did note that before last year, she had seldom seen lion’s mane jellies.

Pershing said many of the reports to the Gulf of Maine Research Institute were from swimmers training for triathlons. At one point the proliferation of jellies had some passing rumors that the July 12 Peaks to Portland race would have to be canceled.

Terry Swain, who has been organizing the swim since 2006, said the race was never in jeopardy, although she took the precaution of making sure all emergency medical technicians were trained on treating jelly stings (with warm water). She had fielded calls in advance of the race, mainly from swimmers training in the Falmouth and Yarmouth area who were anxious about the jellies.

“This was the first year we have ever had anyone talk to us about jellyfish,” Swain said. No one got stung that she knew of. Hypothermia proved the bigger danger of the day.

OCEAN WARMING A SUSPECTED CAUSE

For beachgoers like Murphy, with more than 30 years of experience on these shores, the jelly visitation of 2014 creates a sense of unease. “I just think it is really weird, because we had such a cold winter,” she said.

But a cold winter only affects the water close to the shore, said Pershing. As a whole, the Gulf of Maine is getting warmer, faster than 99.9 percent of the global ocean. “2012 was the warmest summer ever,” he said.

That was the year that Record, of Bigelow Labs, took a group of Bowdoin students out on three research trips, two in Casco Bay and one in the Bay of Fundy. The amount of ctenophores, or comb jellies, that they pulled up in their nets gave him pause.

“When I saw those ctenophores, I thought, ‘Oh, this is warming,’ ” Record said. He emailed Casco Baykeeper Joe Payne, who confirmed he was seeing many ctenophores in the bay as well.

Maine is on track for another warm summer. In June, the average water surface temperature in the gulf was 13.21 degrees Celsius, or about 55.78 degrees Fahrenheit, the sixth-warmest June in NOAA satellite records dating to 1981. In mid-June there was a spike in temperature, as measured by ocean buoys, that Pershing said suggests warmer water offshore was pushed toward the coast, bringing the jellies with it.

From Penobscot Bay to Wells, reports continue to come in of large groups of jellies, called smacks. But for the most part, the jellies have begun to dissipate.

For swimmers and boaters who aren’t enthusiastic about them, Elaine Jones, marine education director for Maine’s Department of Marine Resources, has some good news.

“We won’t see them again until springtime,” she said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.