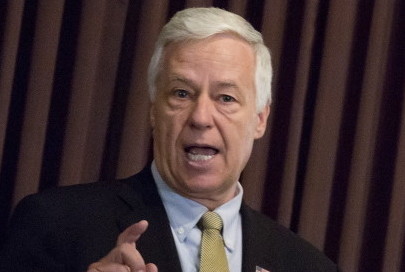

U.S. Rep. Mike Michaud’s campaign for governor was catapulted into the national spotlight in November when he announced in an op-ed column that he was gay. The 58-year-old Democrat, whose political career has spanned three decades, made the announcement reluctantly, citing a whisper campaign and push polls.

If he beats incumbent Republican Gov. Paul LePage and independent Eliot Cutler in November, Michaud will make history and shatter another barrier for the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community by becoming the first openly gay candidate elected governor in the United States.

The historic opportunity of Michaud’s candidacy has drawn the attention and support of national LGBT political action committees and advocacy groups. Some of them are bundling money. Others are planning get-out-the-vote campaigns.

“Electing the nation’s first out governor would be pretty significant in our mind and we believe in the world of politics in this country,” said Charles Wolfe, president and CEO of the Victory Fund, a political action committee that seeks to elect openly gay candidates to office.

But Michaud walks a fine line when it come to the politics of his sexual orientation. While playing up the historic nature of his candidacy has been a boon to Michaud’s national fundraising efforts, it could erode his base, especially among Catholics and blue-collar workers, in the rural and conservative 2nd Congressional District – where some polls show him already losing ground to LePage.

Complicating Michaud’s image is his mixed record on equal rights legislation. Advocacy groups give him high marks on equality issues as a member of Congress, but Michaud cast votes against equal rights in the Legislature in the 1980s and 1990s – a record that could hurt him among progressives in the 1st District.

Cutler, the independent in the Blaine House race, has already criticized Michaud’s legislative record on equal rights.

Political observers don’t expect overt attacks on Michaud’s sexual orientation from LePage and Cutler, but they believe it could affect the way people vote, especially in the privacy of the voting booth.

“There’s many different ways this issue can cut – some ways are positive for the congressman and some ways are negative,” said Mark Brewer, a political science professor at the University of Maine.

Michaud is determined not to make his sexual orientation an issue in Maine. His campaign agreed to an interview on the topic only so long as no questions were asked about his personal life, such as when and how he realized he was gay.

However, Michaud’s identity will be on display next Saturday, when he serves as a grand marshal for 28th annual Portland Pride Parade, a loud and proud celebration of Portland’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and allied community.

The June 21 parade – the climax of a week’s worth of events – draws more than 2,000 participants and thousands of spectators. The parade typically features an enormous rainbow flag and starts at Monument Square, continues up Congress Street and down High Street, ending in Deering Oaks.

Christopher O’Connor, co-chairman of Pride Portland!, said people in the gay community nominated the marshals, and Michaud was chosen for his recent work in Congress and his coming out.

“For us pride is not a political organization,” O’Connor said. “For us, it wasn’t about candidates. It wasn’t a partisan thing. There were no nominations for Cutler.”

‘SAME MIKE,’ DIFFERENT SUPPORTERS

When asked how coming out has affected him personally and politically, Michaud’s answer is always the same.

“Things are great. It’s not an issue. The only people it’s an issue to is the press,” he says. “I’m the same Mike today as I was last year or 20 years ago when I first started. Nothing’s really changed.”

Michaud might be the same, but the political landscape around him has shifted since his announcement.

LGBT advocacy groups and websites have been following his campaign closely, and Michaud has been endorsed by the Victory Fund, the influential Washington, D.C., PAC that supports LGBT candidates. In 2010, the fund poured $2.4 million into the campaigns of 164 national, state and local candidates; 107 went on to win their elections.

Wolfe, the group’s president and CEO, said in an interview May 14 that the group has bundled between $30,000 and $50,000 for Michaud. He declined to disclose the group’s fundraising goal for Michaud’s campaign, other than to say he expects to “far exceed” it.

“You can’t get past the fact that Mike is still relatively new to being an out leader, so there’s a lot of new people for him to meet,” Wolfe said.

Michaud took a big step in that direction in April, when he delivered the keynote address at the Victory Fund’s National Champagne Brunch at the Washington Hilton Hotel in the nation’s capital.

Michaud told the D.C. crowd about the delicious pink cupcakes that were served at his coming-out party on Capitol Hill. He gave a nod to his ability to make history, and the importance of being an out leader.

“As a country boy it is an extremely humbling thing to think about,” Michaud said. “My sexual orientation was never a motivating factor for me to get into politics. And while I am running for governor, it still was never a motivating factor for me to run for governor.”

Michaud related a story about a diner owner in rural Maine who told him that his 15-year-old son came out five months before Michaud did, but only after his son was sick and needed help. The owner said his son found courage after Michaud, a former millworker who is in elected office, came out.

“That’s what it means about being part of the LGBT community – being out front, being willing to tell your stories, (and) not being ashamed of who you are, where you come from,” Michaud said. “I didn’t realize how big a difference it would make by me coming out. But it does make a big difference.”

Michaud also has been endorsed by the Human Rights Campaign, which is active in 200 races nationwide, including a dozen gubernatorial races.

Jeremy Pittman, deputy field director, said the organization doesn’t have a fundraising goal for Michaud but plans to contribute by educating and mobilizing its 8,000 members in Maine through phone calls and action alerts. The campaign’s PAC gave nearly $1.3 million to candidates in the 2011-12 election cycle.

“We know (Michaud) holds a strong commitment to (LGBT) equality and has supported every piece of legislation we have worked on since his first election to Congress,” he said. Michaud supported the repeal of the military’s Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy and has advocated to end discrimination against transgender people.

Pittman said the historic nature of the campaign was a factor in the group’s decision to endorse Michaud and likely will be a part of its messaging to supporters.

Wolfe, at the Victory Fund, said he believes Michaud will benefit politically by being an out candidate because voters will be more likely to trust him on other issues. But Pittman isn’t so sure.

“We’d love to believe that being openly gay can be an advantage in an election campaign, but we have a long history in this country where being openly gay has not been an advantage,” he said.

SPOTTY RECORD ON LGBT ISSUES

Michaud’s campaign has positioned him as a champion for equal rights, but the candidate’s history is more complicated than that.

Michaud is a co-chairman of the LGBT Equality Caucus in Congress, which was established in 2008 and includes more than 100 lawmakers who are not gay, including 1st District Rep. Chellie Pingree, D-Maine.

Pingree has been a member since 2009, but Michaud didn’t join until last November.

Michaud voted repeatedly against anti-discrimination bills in the Legislature, and he was a relatively passive supporter of the same-sex marriage proposal that went to referendum in 2012.

People like Jeanne Paradis of Hampden wanted him to do more for same-sex marriage, especially in the 2nd District, where hearts and minds aren’t changing as fast as in the rest of the state.

“It was disappointing that he didn’t become more involved,” the 59-year-old Paradis said. “Mike took a step back. I wish he would have taken another step forward.”

Michaud, who worked behind the scenes to put the question on the 2012 ballot, said he didn’t take a more public role “because I wasn’t asked.” The campaign focused on stories of everyday Mainers, not politicians, he said.

Michaud’s reticence and spotty record on LGBT rights issues has come under fire from Cutler, the independent in the governor’s race who has a long history of advocacy and financial support for equal rights.

When Michaud won the endorsement of EqualityMaine, the group that led the 2012 same-sex referendum drive, Cutler’s campaign released a statement detailing the 19 votes Michaud cast as a state lawmaker against bills that would have prohibited discrimination based on sexual orientation in housing and employment.

Most of those votes were cast after the 1984 death of Charlie Howard, a gay man who was thrown off the State Street bridge in Bangor and drowned. It was a shocking crime that attracted national attention.

When pressed on those votes, Michaud referred to prevailing attitudes of intolerance and ignorance, noting that some media coverage of Howard’s death seemed to suggest that he somehow invited it.

He also pointed to his support for a hate crimes bill in 1987, saying that measure was seen at the time as “huge progress,” even though references to sexual orientation had to be stripped out to ensure passage.

It wouldn’t be until 2005, after Michaud had been elected to Congress and gone to Washington, that sexual orientation was added to the types of discrimination prohibited under Maine law.

When asked if he felt conflicted about casting votes in the mid-1980s that were effectively against his own self-interest as a gay man, Michaud said, “No.” He declined to elaborate.

His campaign later sent a written statement addressing his legislative record.

“I could make excuses but I won’t,” Michaud said in the statement. “Attitudes about LGBT issues have changed so dramatically throughout my career, both in Maine and nationally. Some people try to run away from their record, but I don’t. My record tells a story of progress.”

Michaud has since improved his standing with gay rights groups, earning a perfect score during his six terms in Congress with EqualityMaine and a 95 percent rating with the national Human Rights Campaign.

James Melcher, a political science professor at the University of Maine at Farmington, said he sees an “interesting twist” in Cutler’s criticism of Michaud’s record. “We have a gay candidate that is being accused of not doing enough for gay people,” Melcher said. “It seems to have some traction, which I find puzzling.”

POLLING CAN BE UNRELIABLE

Attitudes are shifting about LGBT lifestyles. The evidence lies in national polling trends and the growing acceptance for same-sex marriage, largely through court victories.

Polling, however, can be unreliable when it comes to sexual orientation.

Like race, there are culturally acceptable answers to questions about sexual orientation. People tend to provide answers they consider to be acceptable, even though they believe the opposite, a phenomenon known as social desirability bias.

“I think (polls) probably underrepresent the antipathy towards gay and lesbians,” said Andrew Smith, director of the University of New Hampshire’s Survey Center. “You want to appear to be a smarter, nicer, better person to the interviewer than you are in real life.”

Many consider views on sexual orientation and same-sex marriage to be a settled issue in Maine. In 2012, voters passed a referendum legalizing gay marriage. The measure passed with a slim majority of 51.4 percent, or more than 38,000 votes.

But the hard-fought victory was won largely by a large voter turnout in progressive urban areas, whereas rural areas, such as the 2nd Congressional District, continued to oppose it.

Excluding absentee votes, nearly 55 percent of the electorate in the 2nd District voted against same-sex marriage – a margin of more than 31,700 votes. In the more liberal 1st District – i.e., southern Maine – 59 percent of the electorate supported same-sex marriage, outpacing opponents by nearly 68,500 votes.

Public Policy Polling asked Mainers last November whether Michaud’s coming out would make them more or less likely to vote for him. The firm reported that 15 percent of respondents were less likely to vote for him, while 12 percent were more likely.

COSTING 2ND DISTRICT VOTES

When talking to potential donors who are nervous about another three-way race that could put LePage back in office for another four years, Michaud says he has something that the previous Democratic candidate, Libby Mitchell, didn’t: strong support in the 2nd District.

But this campaign is different for another reason: It’s Michaud’s first as an openly gay candidate.

Two recent polls show that Michaud is trailing LePage in an area he has represented for roughly 30 years.

The Pan Atlantic SMS Group-53rd Omnibus Poll, released in April, showed LePage leading Michaud, 43 percent to 34.8 percent, with Cutler polling at 18.8 percent. A Critical Insights poll, released in May, painted the same picture – LePage leading Michaud in the 2nd District, 42 percent to 36 percent.

But Michaud downplays those polls and says he doesn’t believe his sexual orientation is to blame.

“I don’t see any loss of support,” Michaud said. “The enthusiasm and the excitement is the same. Depending which poll you look at will depend on how any individual is in the race.”

But political scientists like UMaine’s Brewer believe that Michaud’s sexuality is costing him some votes among socially conservative Democrats in the district.

“It is a little surprising that Congressman Michaud is not faring a little better in the 2nd Congressional District, which has been in his turf for years, either full or in part,” Brewer said. “I suspect the fact that he came out is costing him among some 2nd District voters. How big that segment is I have no idea.”

Brewer said that Michaud’s sexuality could be a net plus, particularly by appealing to more liberal voters in the progressive 1st District, who might be inclined to support Cutler.

“It’s going to be fascinating to see how that plays out in November,” Brewer said.

This story has been updated to correct the day the 28th annual Portland Pride Parade is being held.

Send questions/comments to the editors.