The bus carrying Mark Rogers and his teammates on the Lancaster Barnstormers rolled through the early-morning darkness and around highway construction sites that made a long trip several hours longer.

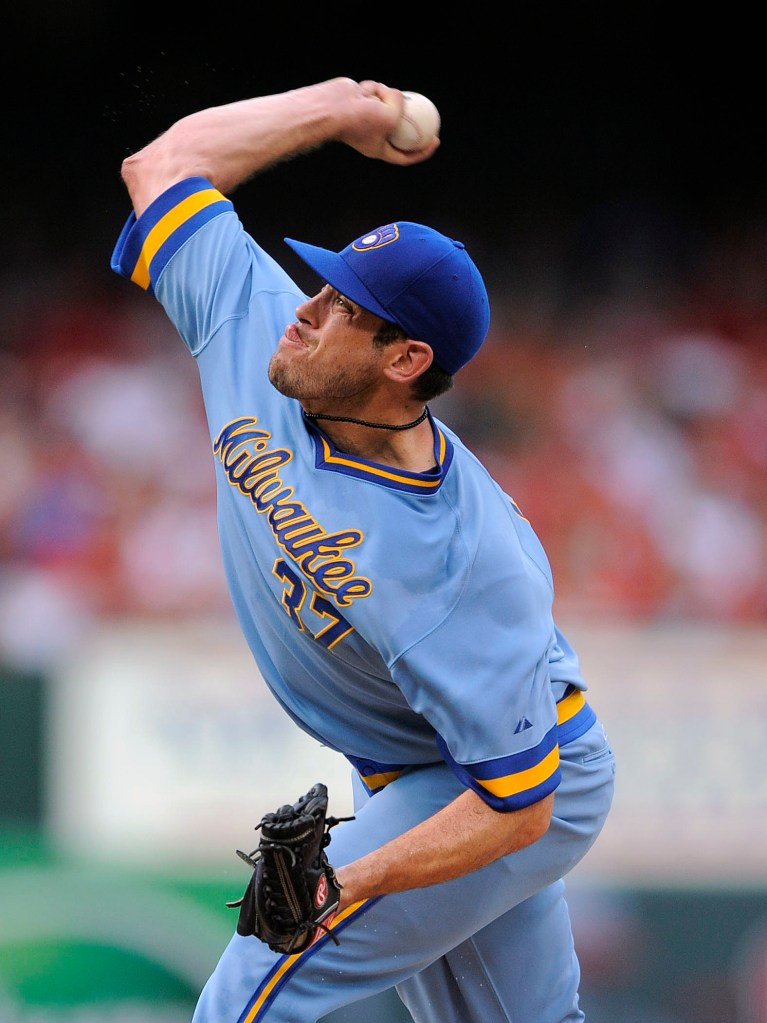

Rogers shifted his 6-foot-3 frame in his seat, searching for physical comfort. He is 10 years removed from being the touted Maine schoolboy pitcher who was the fifth pick in Major League Baseball’s amateur draft. Only two summers ago, he had dominated big league hitters and won ballgames for the Milwaukee Brewers.

And now it is this – hoping to catch the attention of major league scouts while throwing fastballs to castoffs and wannabes in the independent Atlantic League.

Scouts flocked to his games at Mt. Ararat High School in Topsham, radar guns in hand. Milwaukee gave Rogers a reported $2.2 million to sign in 2004, just days after his graduation. Jack Zduriencik, the team’s scouting director, said Rogers could develop into a power pitcher.

“He has the chance, with all the instruction, to really take off.”

Instead, one physical setback after another derailed the potential. Rogers was released by the Brewers at the end of last season. Zduriencik, who moved on to become the Seattle Mariners’ general manager, signed Rogers to a minor league contract over the winter and then released him on May 4, after only two appearances for Triple-A Tacoma.

Rogers no longer had a job in baseball. He went back to his home in Chandler, Arizona, to talk with his wife, Kerrie, and feel the joy of their 2-year-old daughter, Ellyette, running into his arms.

Back in Maine, his friends and fans grieved what they feared was the end of a career that was never truly realized. Wasn’t it time for Rogers, at 28, to be thinking about the rest of his life?

Rogers signed with the Barnstormers, an Atlantic League team in the small Pennsylvania city of Lancaster, near Amish settlements.

As Thursday night slipped into Friday morning, Rogers found his mental comfort. Lancaster had beaten the Long Island Ducks, 4-1, hours earlier.

Rogers started the game. He allowed the Ducks’ only run in the first inning, when he was unsettled. Pitching coach Rich Rundles, whose own playing career ended prematurely last season after knee surgery, went to the mound.

“What are you feeling?” asked Rundles. Too much, not enough, said Rogers.

“Let’s just simplify everything,” said Rundles. “Take the ball out of your glove. Know where you’re putting your foot down (on the delivery) and where you’re putting your hand down (on the release).”

Rogers didn’t allow another run over the next five innings. He struck out five and walked one. The velocity of his fastball was back up, from 93 to 96 mph. His command was back.

When Rogers returned to his hotel room in Lancaster at 5:15 a.m., he was tired. He also was satisfied, if not content. He could have pitched better. But he had pitched well.

Teams in the Atlantic League aren’t part of any major league farm system. Financial stability is a challenge. Player are paid through sponsors’ advertising and ticket revenue. Better players might earn $2,250 a month during a four-month season.

Thursday night, a crowd of about 4,400 attended the Lancaster-Long Island game. Last Sunday in Lancaster, about 3,800 watched the York Revolution play the Barnstormers in a doubleheader.

Some see the Atlantic League as a league of last chances for veteran players who fight to return to the major leagues, or youngsters who hope to get noticed. Others see it as a first step back to a career.

“I love baseball,” Rogers said before Friday night’s home game. “If I’m healthy, you’d have to put me in handcuffs and drag me away before I stop. I’m blessed just to be where I am.”

He watched the movie “Cinderella Man,” the story of Jim Braddock rising from local fighter to world heavyweight champion. Braddock kept picking himself back up after getting knocked down. “It inspired me,” said Rogers.

He remembers winning three of four games he started for the Brewers in the late summer of 2012. He struck out more than a batter per inning. He was the power pitcher they had expected him to be.

“It was amazing. The weight was lifted off my shoulders. I felt joy. I felt confidence. There was no next level to get to.”

The Brewers shut him down before the season was over, hoping to keep his surgically repaired right shoulder healthy. Despite the precautions, his problems returned and he was released.

He says Seattle cut him because it had too many pitchers coming back from injuries and not enough innings to provide the work he needed to get back the velocity and command that every pitcher needs.

“You can pitch all you want in a bullpen, but it’s not the same,” he said. “When a batter steps into the box, the adrenaline kicks in. Everything changes. It’s a real game situation.”

Working with his agent, Ivan Hand, Rogers targeted Lancaster for his return. He would pitch every fifth day for Manager Butch Hobson, a former Boston Red Sox third baseman and manager. Hobson has contacts, although major league scouts are fully aware of Rogers and his new situation.

Rogers has won two of his three starts, and both victories were considered quality performances.

“I see a competitor,” said Rundles, who is only four years older and pitched briefly for the Cleveland Indians in 2008 and 2009. “When he’s healthy, he dominates hitters.

“He can get back (to the major leagues). It’s not like he has a lot of flaws. Mark just needs to find his consistency, and that comes with repetitions, using the same mechanics. I know (scouts) are watching.”

It doesn’t matter that the independent leagues are the lowest rungs on baseball’s ladder. It’s still the ladder. Scott Kazmir, once a top prospect of the New York Mets and later a top pitcher for the Tampa Bay Rays, was ineffective for much of three seasons from 2009-11 before he was left without a job in 2012.

Kazmir signed with the Sugar Land Skeeters of the Atlantic League for that season. In 2013, he was one of the comeback stories of the year while pitching for Cleveland. He signed a two-year contract with Oakland during the off-season and is now the A’s top pitcher.

“One of the great things about this league is that there are no politics,” said Rogers. “If you’re pitching, you’re going to play. If you’re swinging the bat well, you’re going to play.

“I run into players all the time who are still chasing the dream,” he said. “The level of respect we have for each other is extremely high.”

Rogers’ voice broke when he talked of the support his wife has given him. She’s pregnant with their second child. He sought out a financial adviser after he got his signing bonus and says his family will be fine while he chases his dream.

His wife and daughter will join him for Father’s Day weekend when Lancaster is in Bridgeport, Connecticut, to play the Bluefish. Rogers’ family from Maine will visit as well.

“That I can do this is a blessing,” said Rogers. “I’m extremely fortunate. God surrounded me with a great support system.”

That includes Bill Swift, the South Portland native and former University of Maine star pitcher who had his own major league career with several teams, including Seattle, San Francisco and Colorado.

Now the baseball coach at Arizona Christian University in Scottsdale, Swift has become a mentor and big brother to Rogers.

“Baseball owes me absolutely nothing,” said Rogers. “I love this game.”

Steve Solloway can be contacted at 791-6412 or at:

ssolloway@pressherald.com

Twitter: SteveSolloway

Send questions/comments to the editors.