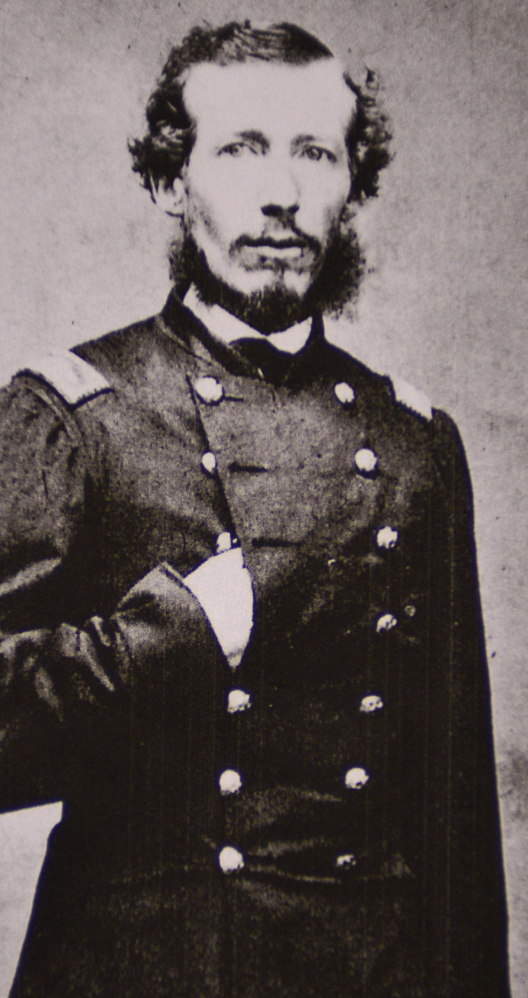

He’s not what you’d call a Civil War legend. In fact, Col. Sabine Emery’s remains have long lain in Portland’s Eastern Cemetery without so much as a headstone to tell the world that here rests a genuine Maine hero, a young officer who fought – and nearly died – preserving the Union in 1863.

That will change Saturday.

“I’ve got a file drawer full of these guys’ names and they’re all important – don’t get me wrong,” Ben Smith said as he stood Monday over Emery’s freshly planted, white-marble headstone. “But he’s particularly important because of who he was and what he did.”

Smith, a retired Cumberland County Jail officer, has spent the last 20 years doing his part (and then some) to research and, when necessary, resurrect Maine’s Civil War legacy. Col. Emery is, as he put it, “a great find.”

It began simply enough: Smith’s daughter asked him one day if he’d ever undertaken a family genealogy, which he hadn’t. As he dove into the project, Smith quickly discovered that his great-great-grandfather Llewellyn Smith had served as a private with the 9th Maine Volunteer Regiment at the famous Battles of Fort Wagner in South Carolina in the summer of 1863.

The bloody campaign has been immortalized in the film “Glory,” which commemorates the 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, the Union Army’s first all-black unit, as it tried to take Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863, and was all but decimated by a Confederate fusillade that repelled the attack.

The 9th Maine, it turns out, was directly behind the 54th and also suffered devastating losses. Smith eventually discovered that his great-great-grandfather survived Fort Wagner, but later died as a prisoner of war and was laid to rest in the central Maine town of Carmel.

“So then I took a particular interest in the guy who led the 9th Maine,” Smith recalled. “And that was Col. Emery.”

Born in Eastport in 1834, Emery graduated from Colby College in 1858 and became a school teacher before entering the Army as a captain in 1861. He rose quickly through the ranks and ultimately led the regiment in the capture of Hilton Head, South Carolina, and later in the attacks and subsequent siege on Fort Wagner, on South Carolina’s Morris Island, which commanded the southern approach to Charleston Harbor.

It was, as Emery would later detail in a letter to Maine Gov. Abner Coburn, the bloodiest of battles.

“The entire loss to the Regiment in killed and wounded in the capture of the Island and the assaults on Wagner will not be far from two hundred,” he wrote.

Among those wounded was Emery himself. He took a bullet in one leg and a piece of shrapnel in the chest, and might have been left for dead had a litter bearer not noticed him still breathing as he lay on the battlefield.

“He never fully recovered from his wounds,” said Smith, who followed Emery’s story back to Maine after his resignation from his commission in 1864.

From here, Emery took his wife, Louisa, and their two children to the warmer climate of Baltimore, where he became a lawyer. Four years later, according to his obituary, Emery died “of lingering consumption.” He was only 34.

Smith, like any historian, wanted to punctuate his research by locating Emery’s final resting place. But the more he looked for it over the next 15 years, the murkier things got.

He connected via a Civil War website with Emery’s great-great-granddaughter in Ohio. She knew all about the colonel, but hadn’t a clue where his body had ended up.

Smith also contacted Roger Hunt, a historian in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, who wrote about Emery in his Civil War book “Colonels in Blue.” But Hunt, too, had struck out on the gravesite.

Hunt, like Smith, had even gone to Eastport – twice – to scour the Emery family cemetery there. Plenty of Emerys, but not one named Sabine.

Again just like Smith, Hunt had chased down the obituary’s reference to the Greenmount Cemetery in Baltimore, where old records indicated Emery had been placed in a temporary receiving vault.

“Which today is empty,” Smith said.

Finally, just over a year ago, Smith was perusing the records for Eastern Cemetery, at the base of Portland’s Munjoy Hill, in search of another Civil War veteran whose surname began with “E.”

“I’m going down through the ‘E’s and all of a sudden this name pops up – Sabine Emery,” Smith said. “That’s all there was – no military rank, just the date of death.”

But that date – March 24, 1868 – matched the colonel’s death.

“I remember saying ‘Oh my God, this is him,’ ” Smith said.

But how? The heavily weathered marker over Section A, Tomb 2, is marked “Gould.” And while the records show 18 people, including Emery, buried in the tomb, there’s no explanation of how he got there.

Back to the great-great-granddaughter, who told Smith that Emery’s lonely wife took refuge with relatives in Portland while he was away at war. Thus, they agreed, she must have brought his body back to Portland after he died and, without fanfare, had him buried here in the extended family’s plot.

“My guess is that she was so distraught, she just wanted to get him in the ground,” Smith said. “No service, no colonel, no 9th Maine, nothing.”

(Louisa Emery is buried in Santa Monica, California, where she moved to be close to her daughter.)

Working with Paul DiMatteo, owner of Maine Memorial in South Portland, Smith next dispatched letters to the Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Sen. Susan Collins.

He explained how valiantly Emery fought at Fort Wagner. How, after years of searching, Smith had located Emery’s remains. How a marker telling visitors to Portland’s oldest cemetery that here lies Col. Sabine Emery “is long overdue.”

The gravestone arrived – free of charge – at Smith’s home in Portland late last fall. Last week, Smith helped Joe Dumais, Portland’s parks and cemeteries manager, install it.

“It was my honor,” Smith said.

As it will be on Saturday at 1 p.m., when Col. Sabine Emery, 150 years after he led his fellow Mainers directly into Confederate fire, gets the send-off he always deserved.

Civil War re-enactors will be there, bearing the colors not only of the 9th Maine, but also the 54th Massachusetts, the 3rd Maine Regiment Volunteer Infantry and the 1st Maine Cavalry. The Rev. Jeff McIlwain of Portland will offer a prayer. Local historian Herb Adams will speak.

So will Nancy Tidrick, Emery’s 67-year-old great-great-granddaughter. She arrives in Maine today after driving all the way from Ohio.

Ten years ago, Tidrick transcribed and published her great-great-grandfather’s war journal, the original version of which has been handed down through generation after generation of his descendants.

But to stand over his long-lost burial site? How will that feel?

“It isn’t really quite real to me,” Tidrick said via her cellphone Thursday. “I think when I get to the cemetery, it will take my breath away.”

Better late than never.

Send questions/comments to the editors.