Gov. Paul LePage says he is willing to allow some family members of opiate addicts to have a drug that reverses the effects of an overdose, but advocates of broader access to naloxone say his proposal doesn’t go far enough.

LePage said Wednesday that he has worked with Rep. Barry Hobbins, D-Saco, to find common ground on a bill that would provide access to naloxone for family members who might be in a position to save a loved one from death or brain damage.

LePage’s comments reversed his earlier stance against expanding access to naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan. He had adamantly opposed allowing family members to have Narcan, saying that easy access to an anti-overdose drug would make people more prone to continuing opiate use because they would have a safety net.

Supporters of the proposal say naloxone can save lives and give addicts a chance to get into treatment.

LePage said any family member prescribed Narcan to have in case of an overdose would have to get training and have the addict sign a waiver allowing its use on him or her.

The governor did not explain the reason for his changed stance on the issue. His press secretary, Adrienne Bennett, did not return calls for comment Wednesday.

In Maine, naloxone is now available to addicts by prescription. Health care professionals may administer the drug. Among emergency workers, only paramedics and advanced life support medical personnel are allowed to administer naloxone.

Seventeen states and the District of Columbia allow the drug to be distributed to the public. Of the six New England states, only Maine and New Hampshire do not have laws giving third parties, including family members, access to naloxone.

Rep. Sara Gideon, D-Freeport, the sponsor of a bill to expand access, said the governor’s proposed compromise is an important step. “We feel that this is immediately going to be able to save lives,” she said.

Gideon’s bill is a response to a growing problem with opiate addiction, specifically overdose deaths, in Maine and nationally.

The number of opiate overdose deaths in Maine rose from 156 in 2011 to 163 in 2012 – almost the same number of people who died in traffic crashes that year.

The number of overdose deaths attributed to heroin quadrupled from seven in 2011 to 28 in 2012, the last year for which figures are available. The state medical examiner expects the total for 2013 to be higher still, and treatment professionals say that number is likely to grow as people who are addicted to prescription painkillers switch to heroin, which is now cheaper and more available.

The issue gained notoriety this year with the death of actor Philip Seymour Hoffman of an apparent heroin overdose.

Kenny Miller, executive director of the Ellsworth-based Down East AIDS Network, said the governor’s new position is a positive sign but doesn’t go far enough.

“Any move the governor makes walking back from his original opposition is progress,” Miller said. But restricting access to naloxone to immediate family members will leave many people vulnerable, he said.

“The vast majority of people who overdose do so in the presence of others. They’re either using with others or there are others in the household,” Miller said. “In some respects, a first responder might have more of an effect than just the nuclear family, because it’s the rare parent who is prepared and interested in equipping themselves” with naloxone.

Miller said the best way to get naloxone kits to people who are most likely to prevent overdose deaths is to distribute them through third parties such as needle exchange programs.

Despite the governor’s previous assertions, advocates say, there has been no evidence of any increase in heroin use in states that have expanded access to naloxone.

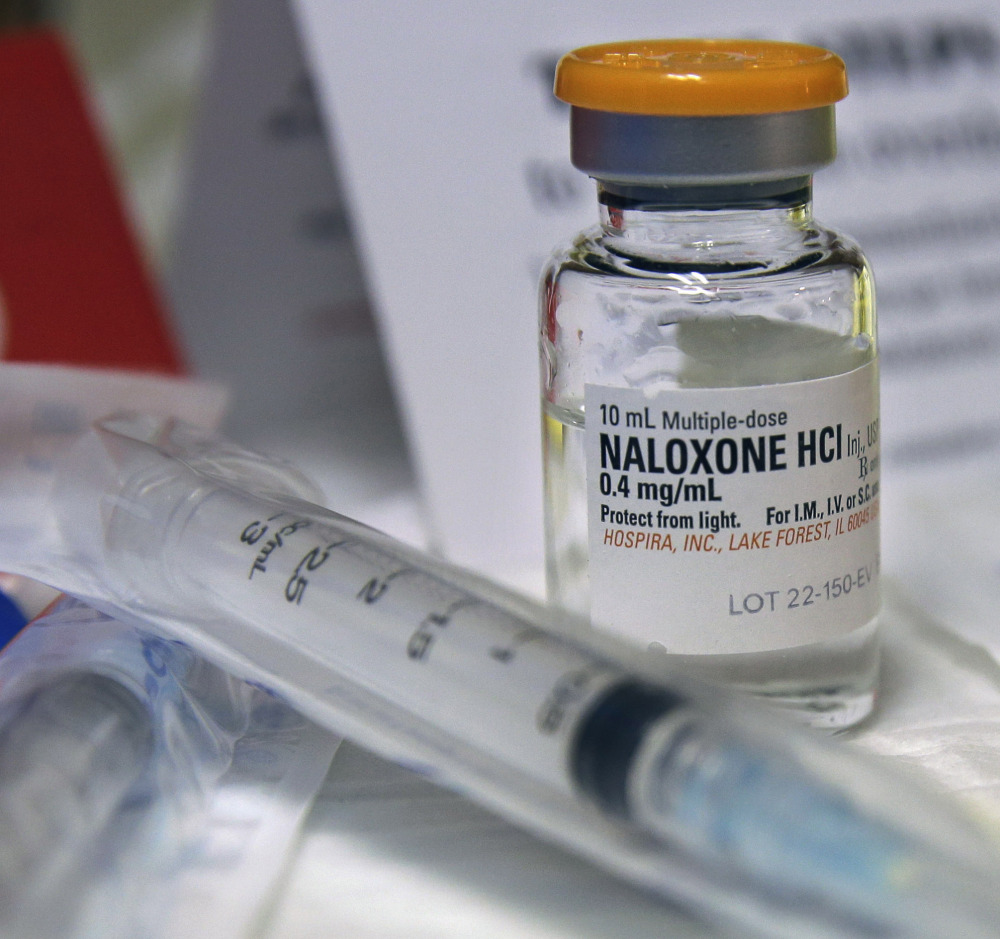

Opiates like heroin, methadone and oxycodone slow a person’s breathing, sometimes to the point where the heart and brain don’t get enough oxygen to survive. Naloxone immediately counteracts the effects of the opiate.

Portland firefighters have carried Narcan on all fire trucks and ambulances since 2002, when there was a surge in methadone overdose deaths. In 2011, Portland firefighters administered 60 doses of Narcan. The number climbed to 65 in 2012 and to 93 in 2013.

Gideon’s bill would allow family members and friends of opiate users to obtain naloxone, and allow police and emergency medical technicians to administer the drug.

The bill, L.D. 1686, was endorsed by the Legislature’s Health and Human Services Committee but has not been brought to the floor of the House while legislators have worked with the administration on a compromise.

Republicans, the minority on the committee, recommended passage of a less ambitious bill, to allow police and rescue workers to carry naloxone.

The governor’s proposal includes no provision for police or emergency medical technicians to carry naloxone, Gideon said.

“In rural areas of the state, law enforcement may be the first to show up by an hour before” emergency medical services, Gideon said. “That is the chance to save lives in the hardest-hit areas of the state. The rise of heroin in the rural areas is really potent.”

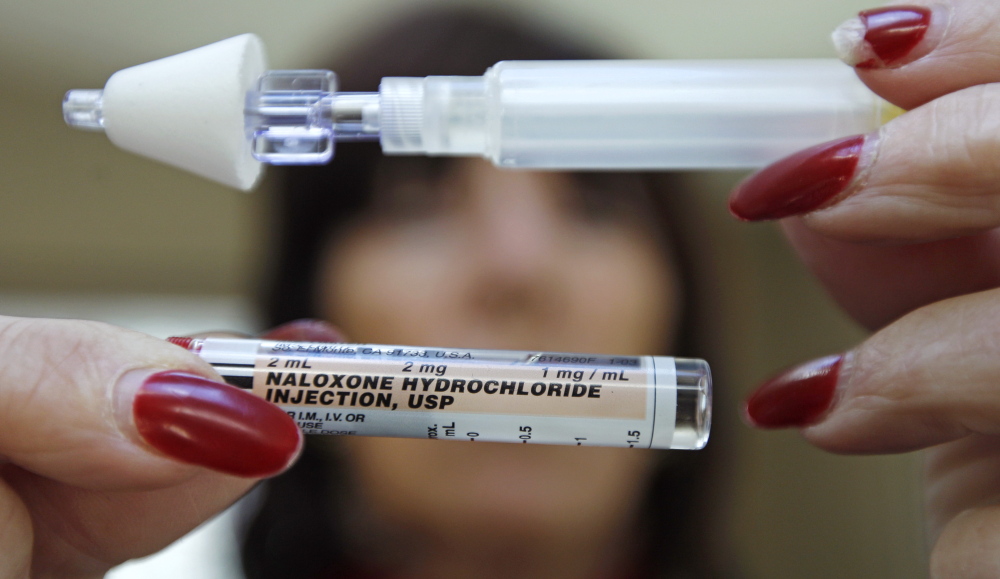

Naloxone has become much easier for people without medical training to use since a mechanism was developed to deliver it by nasal spray. Last week, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the use of an automatic injector designed for family members and caregivers.

LePage remains opposed to making naloxone commonplace, maintaining that easy access would encourage heroin use.

“I just don’t think it’s appropriate, with liability issues, to open it up and say, ‘Be a drug addict and we will allow you to have everyone on the street to have a little pen and we can inject you,’ ” he said. “That’s what they were asking for, basically. I’m saying no.”

Gideon said she believes that the governor has come to understand that addiction is a disease that affects a broad cross-section of Mainers.

“The problem of drug abuse crosses social and economic lines,” Gideon said. “Addiction is a really, really powerful thing, and not an indication of somebody’s moral character but something beyond their control.”

Staff Writer Matt Byrne contributed to this report.

David Hench can be contacted at 791-6327 or at:

Twitter: @Mainehenchman

Send questions/comments to the editors.