Maine has a history of sending leaders to the U.S. Senate. It is unlikely there were two more significant colleagues in the Senate’s nearly 140-year history than the 1959-1972 combination of Margaret Chase Smith, a Republican, and Democratic Edmund S. Muskie.

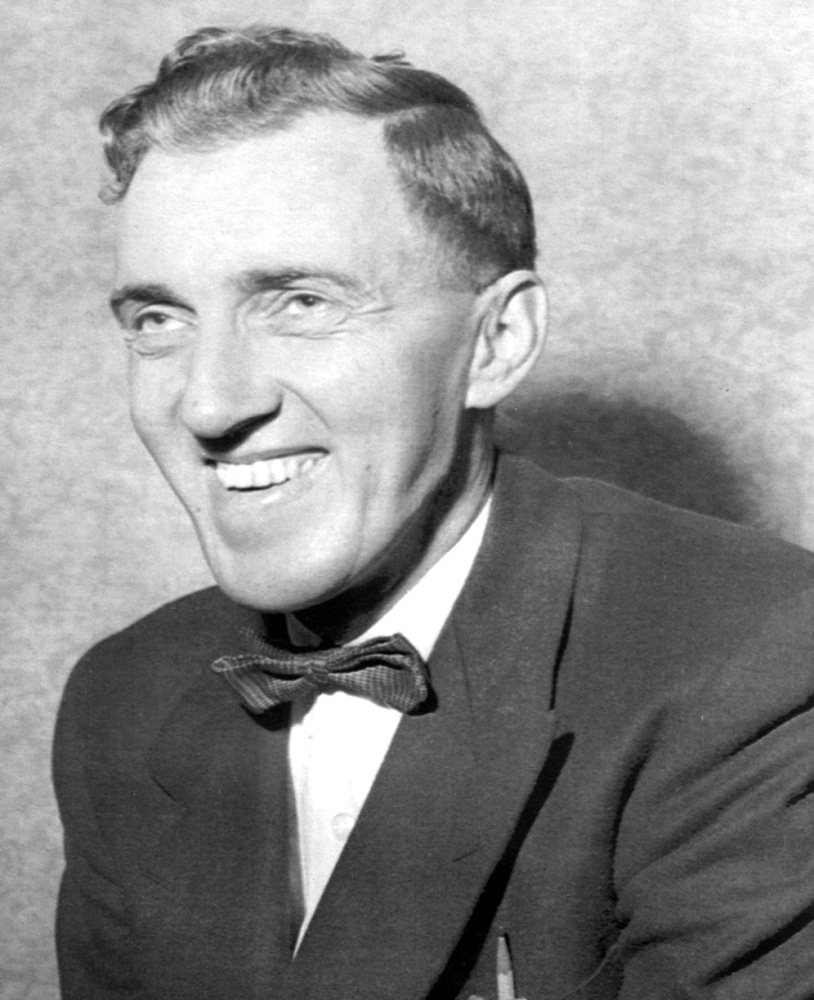

I want to recall the latter because, on March 28, we will celebrate the 100th anniversary of his birth.

Ed Muskie is the father of national environmental law: the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act and, by extension, Superfund.

Muskie was born of Polish immigrants in the town of Rumford on March 28, 1914. He attended Bates College and Cornell University Law School. While he was more than 6-foot-4 and played some basketball, his pride was his performance in debate. It was this skill that gained him a reputation as a formidable force in his political life.

Sixty years ago this fall, Muskie was elected to the first of two terms as governor of Maine. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1958. This was the last year of September elections in Maine – a fact that generated the expression, “As Maine goes, so goes the nation.”

In fact, the election of 1958 resulted in a sea change in the Senate, what today would be called a “wave” election. One of 16 new Democrats, Muskie was a member of the largest single-party gain in the Senate’s history.

Muskie immediately got in trouble with then-Majority Leader Lyndon Baines Johnson and was thus assigned to three minor committees. While his preference was for Foreign Affairs, he was put on Government Operations, Banking and Currency and Public Works. History will show that he ignored the insult and used his position on those committees to build a legislative record unparalleled in American history.

Not only did he write the fundamental environmental laws that today are accepted as basic rights by most Americans, but he also led shaping Model Cities legislation as a member of the Senate Banking and Currency Committee and the Congressional Budget Act as a member of the Government Operations Committee. Ironically, President Johnson had to prevail personally on Muskie to guide the Model Cities bill through the Senate.

I would be remiss to not note that Model Cities included a very special Muskie amendment – the Historic Preservation Act – that has resulted in preservation of many of the nation’s most precious historical structures.

Muskie’s environmental record radiates across the world. The Clean Air Act is an international model for legislation and regulation around the globe. Many question how such a far-reaching, invasive law could have been enacted. But as a result of that law, the air is cleaner, cars and factories pollute less, the science of health effects of pollution is accepted and people are healthier wherever it has been adopted.

Muskie’s role in the Senate did not stop with the work required by the committees on which he served. He was an integral part of the liberal bloc of senators, both Republican and Democratic, who provided the working majority for the landmark social and civil rights legislation of the Johnson era. He was one of the principal reasons why President Jimmy Carter was able to see his Panama Canal Treaty ratified by the Senate. He also carried out a special mission to Germany for Carter to try to moderate the criticism of the president by then-Chancellor Helmut Schmidt of Germany.

And Muskie’s career did not end with his retirement from the Senate. Indeed, it was his appointment to the role as secretary of state that led to that retirement. As secretary of state, he played a lead role in the negotiations to bring home the State Department employees who had been held hostage in Iran for more than a year.

Virtually unknown to the nation, several years after he left the federal government, Muskie was called upon by President Reagan’s chief of staff, former Sen. Howard H. Baker, to help calm the presidential rhetoric against what was then the Soviet Union. Muskie had worked closely with Baker in the development of the Federal Clean Air and Clean Water laws. At Baker’s request, Muskie met with former President Richard Nixon at Nixon’s home in Saddle River, N.J., to discuss how to convey a message to Reagan, and later met with Reagan to discuss the risks of all-out confrontation with the Soviets.

Nixon and his colleagues were responsible for myriad “dirty tricks” dumped on the Muskie presidential campaign in 1971 and 1972, which many, including Muskie, believed derailed that campaign. But Muskie set aside his personal animosity toward Nixon to help his country.

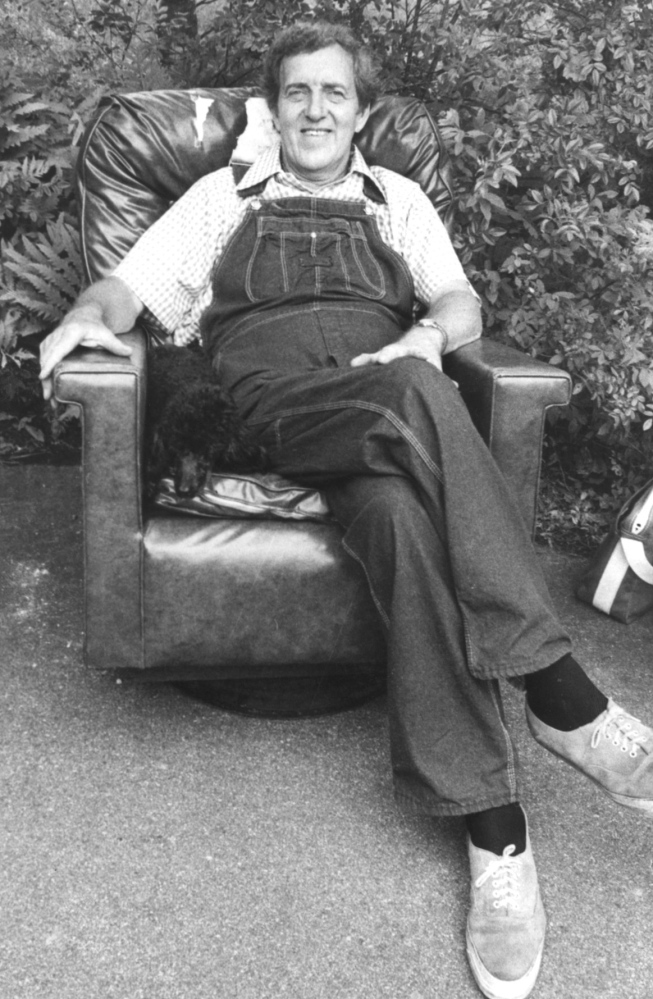

Muskie’s role in public life was not to end there. While he assumed several civic tasks in Maine during his later years, he spent a great deal of time trying to stabilize a very unstable Cambodia. Many, including this author, believe that it was those long flights to Cambodia that caused the blood clot in his leg that eventually led to his death. But Muskie was doing that to which he had committed his life: serving the Republic for the good of the Republic even if it meant personal sacrifice.

The Edmund S. Muskie School of Public Service at the University of Southern Maine and the Edmund S. Muskie Archives at Bates College are institutional memorials to him. The laws he wrote and the ideal of public service he represented are his lasting legacy. Maine should celebrate his life for his gifts to our country.

– Special to the Telegram

Send questions/comments to the editors.