Abby Snyder pokes her head into Carter Blanche’s room at the Barbara Bush Children’s Hospital. “You ready for class?” she asks the 6-year-old boy, who has cystic fibrosis and is back for another week-long treatment. “We have a spelling test today!”

“Yep!” he says with a big grin, looking over at his dad, Josh.

Snyder is the in-house teacher at the pediatric center, a hospital within a hospital at Maine Medical Center in Portland. Although on-site teachers are common at large pediatric hospitals in big cities, Snyder is the only one in Maine.

“Parents are completely surprised to find a teacher here,” she said.

If a child is too sick to do any schoolwork, Snyder can advocate for the child to ensure that school officials understand the situation. For children who are well enough, she works with their teachers and keeps them up to speed so they don’t end up facing piles of homework and missed tests when they return to the classroom.

For some children, technology can help bridge the gap between school and a hospital bed. Snyder can get a student a laptop or arrange a video link to the classroom using Skype.

Snyder works with about a dozen children a day, on average, and can be called in to work with school-age children in other parts of Maine Medical Center, such as teen mothers on bed rest in the prenatal unit.

For advanced math and science, Snyder calls in Anthony King, a former classroom teacher who volunteers at the hospital. A Classics major, he has helped students with Advanced Placement Latin homework, too, she said.

LINK BETWEEN PATIENTS, SCHOOLS

Snyder is the fourth person to hold the job since the part-time, contract position was created. She said she usually works full-time during the school year and about 15 hours a week in the summer.

Her classroom is tucked into a corner, its walls lined with books and packed with everything from flashcards for youngsters to a model of the universe. Origami cranes dangle from the edge of a whiteboard, and an enormous hand-drawn green dinosaur competes with handwritten thank-yous to Snyder over a desk.

Every day, Snyder checks in with school-age children on the floor. She works with parents, contacts school officials and teachers to explain why a child is out of school, and arranges for appropriate schoolwork.

When a child is hospitalized, getting in touch with school officials can be the last thing on parents’ minds, she said.

Snyder said patients like Carter, who have chronic or long-term illnesses that put them in the hospital regularly, become particularly special to her.

“I get some continuity,” said Snyder, who keeps special folders for those patients.

Carter’s father, Josh Blanche, said Snyder has made a huge difference to his son. And he’s grateful to know that the program is there for his 3-year-old daughter, Emma, who also has cystic fibrosis and already needs regular hospitalizations that last at least three weeks at a time.

For Carter, having “his teacher” there makes his stays in the hospital more bearable.

“Without (the classroom program), I just can’t imagine it. It would make for a very long time in the hospital,” said his father. “When (Carter) comes here, he’s looking for a couple of faces, and Abby’s is one of them.”

PROVIDING SEMBLANCE OF ‘NORMAL’

The Barbara Bush Children’s Hospital is filled with light and homey touches. Cartoons are painted on windows, and a picture of the former first lady fist-bumping a patient hangs on a wall.

As Snyder walks through the unit, she steps aside for a young girl wearing a hospital gown who zips down the corridor on a pink Big Wheel tricycle. Other ride-on toys are parked by a sunny atrium with couches and easy chairs.

For Carter, it’s time to get to work.

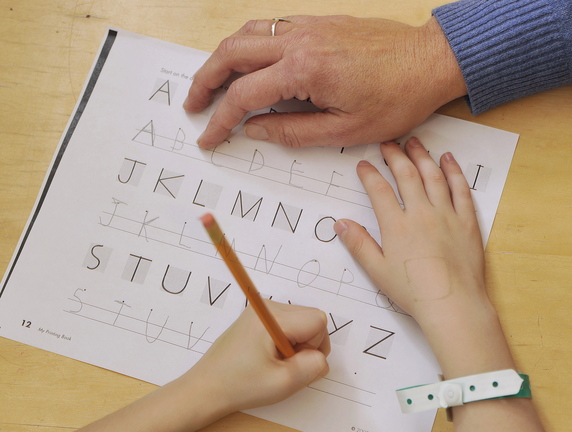

At a child-sized table, he’s whisper-reading a “Splat the Cat” book to Snyder, fidgeting on his knees with excitement. When he gets to the last word on the page, he and Snyder shout it out at the top of their lungs.

“Got you!” Carter says gleefully, pointing at Snyder. “You got me!” she responds with a laugh. The only sign that Carter is in a hospital is his brief coughing fit and a green-and-white plastic identification bracelet.

It’s that kind of “normal” that makes Snyder’s work so important, say parents and nurses. She doesn’t do any medical work, and the kids know she’s there in a different role from the nurses and doctors.

“Everybody loves her,” said pediatrics nurse Jessica Rock, including one regular patient who reads a particular book series with Snyder at the hospital – and refuses to read the series when she’s out of the hospital.

Walking down a hall, Snyder pokes her head into a room: “Hey, you still have that gum?” she asks.

The boy hadn’t been allowed food or drink by mouth for a week, so when he was cleared to eat ice chips and chew gum, she bought him gum.

“It gives them something non-medical to look forward to,” said nurse Jessica Howe. “It’s very important. She’s a good liaison to the schools, and the kids have anxiety about missing school.”

a great help for families

Snyder first learned about the job when she was teaching at Hall Elementary School in Portland. One of her students was diagnosed with leukemia and spent almost two years in and out of the pediatric cancer center at Maine Med. Today, he’s in college and cancer-free.

“I became close to him and his family, and I spent a lot of time on the unit,” she said. Along the way, she got to know the in-house teacher at the time.

“I always thought at the back of my mind, ‘What a cool job,’ ” Snyder said. When the job was posted, she didn’t hesitate.

“I thought, ‘I want that job. I need that job,’ ” said Snyder, whose student was her inspiration.

She, in turn, is inspiring her students and their families at the hospital. A recent photo of her on the hospital’s Facebook page quickly racked up dozens of messages from grateful parents.

“Abby ur so special!!!” wrote Morgan Gryskwicz of Standish, whose 13-year-old daughter, Emily, has been in the hospital regularly over the last year for cancer treatments. “Emily loves school and her stays in the hospital were only made better knowing she had u to study with.”

Gryskwicz said Snyder worked tirelessly with the school and Emily to keep her on track with schoolwork and provide a break from the medical pressures.

“She meant the world to our family,” said Gryskwicz. “Any time we were in there, Abby would quickly get in there and Emily didn’t feel like she missed anything.”

She also mixed up a bit of fun with the schoolwork. On a summer day, Snyder helped Emily and other patients make sand castles – out of crushed graham crackers.

“She went down to Haven’s (Candies) and bought seashell candies to decorate them,” Gryskwicz said. “The projects she came up with were fun and different. It just made a huge difference.”

Snyder said she’s the lucky one. “I love this job.”

Noel K. Gallagher can be contacted at 791-6387 or at:

ngallagher@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.