Kimberly Richards still remembers how it felt, back in the sixth grade, when she suffered her first episode of bronchitis.

“It was upsetting, because at that age I was just getting into sports … basketball and softball,” Richards said. The bronchitis – which has become chronic in her life when she is home in Eliot – “definitely affected” her ability to play, leaving her short of breath and lacking stamina, she said.

“It resulted in me having to be put on an inhaler. It was scary, because I had seen other kids on inhalers, and I knew it was something serious,” said Richards, now 34.

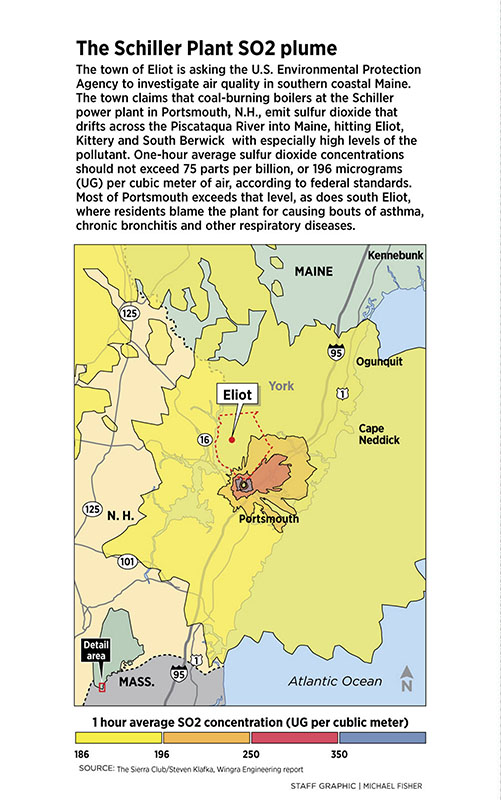

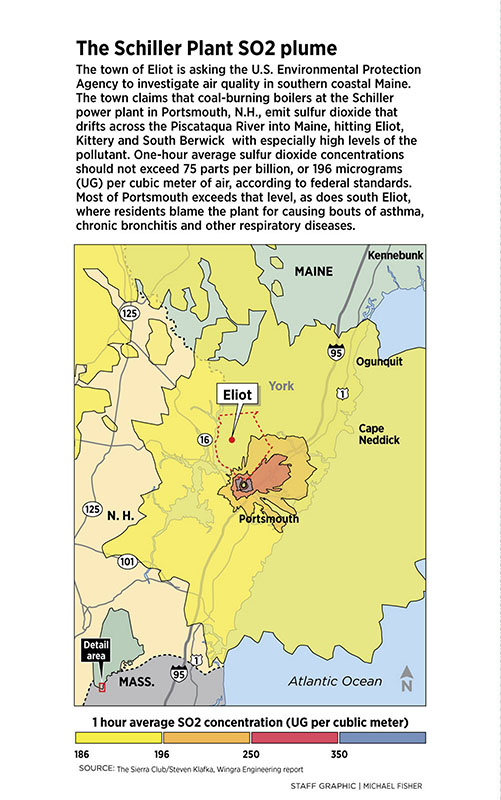

A graduate student in public policy and management at the University of Southern Maine, Richards said that although she has no proof, she believes that her bronchitis was caused at least in part by air pollution emitted from the Schiller Station power plant in Portsmouth, N.H. At the closest point, the plant lies just several hundred yards from Eliot across the Piscataqua River – a natural border between Maine and New Hampshire – and its stacks produce emissions including sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides. Many Eliot residents say the pollution may pose respiratory health problems in their town. Schiller vehemently disagrees, citing the fact that Maine’s own asthma surveys do not bear out the residents’ claims.

“We are very cognizant of what we are emitting,” said Martin Murray, spokesman for Public Service of New Hampshire, which owns and operates the Schiller plant and a second in nearby Newington, N.H.

“We have stack testing by the state of New Hampshire, (and) there have been no violations of these emissions,” Murray said.

Schiller produces energy with three 50-megawatt boilers and generates 150 megawatts of electricity for an estimated 150,000 homes, said Murray. Two boilers burn coal and the third, originally coal burning, was replaced in 2006 by a boiler fueled by wood. That measure alone reduced sulfur emissions by a third, he said.

Whatever cleanup or reduction of pollutants the plant has achieved, it is not enough to satisfy town residents like Richards, who is a passionate spokeswoman for Eliot’s right to a healthy environment. She is the founder of Citizens for Clean Air, Eliot’s grassroots advocacy group, working to help persuade the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to investigate elevated levels of sulfur dioxide in town and to determine whether the pollution is being dumped by Schiller Station onto this small rural community of about 6,000 residents.

Twenty-five years after Richards’ initial diagnosis of respiratory problems, the experience spurred her to lead town residents in a referendum last summer to request that the EPA investigate Schiller’s emissions. Their petition claims that the plant’s releases of sulfur dioxide are making it impossible for the town to comply with the federal government’s National Ambient Air Quality Standards. Eliot does not violate Maine’s clean air standards, and Schiller’s emissions fall within limits allowed by New Hampshire, but they fall short of federal compliance.

In early 2012, the Sierra Club – as part of its $30 million national campaign, Beyond Coal, examining the link between carbon pollution and compromised air quality all across the nation – approached its members in Eliot about taking on Schiller and the problem of sulfur dioxide air pollution in town.

Citizens for Clean Air, armed with $20,000 worth of sophisticated modeling of pollution patterns and help with organizing – both provided by the Sierra Club – lobbied Eliot residents to vote in the referendum to petition the EPA for an investigation of air quality there. The measure passed by a 2-to-1 margin, evidence of the conviction of many townspeople that more than a half-century of coal burning by Schiller has taken its toll – particularly among residents in South Eliot nearest the plant.

“They take the brunt of any of the pollution (from) Schiller,” said Richards. “We want (EPA) to come in and find out if Schiller is polluting our air.” If so, Richards said, the problem needs to be fixed – either by the shutdown of the plant or cleanup of its emissions.

Many coal-burning power plants from the 1950s are being decommissioned or shut down in the U.S., said Glen Brand, director of the Maine chapter of the Sierra Club. These closings offer an opportunity to communities and companies to replace fossil fuel with cleaner energy, he said, and old cold-burning plants like Schiller represent the “low-hanging fruit” for those who want to realize a transition to cleaner green energy.

Schiller officials are skeptical of the Sierra Club’s motivations and believe the environmental organization has been the mover and shaker behind the Eliot petition.

“They just went after us to create an opportunity to prevent the plant from continuing,” Murray said.

“The idea was to make coal or whatever polluter pay for cleanup as a matter of regular course,” Brand said. “Our goal is not to shut down plants. … We want the air to be cleaner. How ever that works out is up to Public Service of New Hampshire.”

The petition submitted by selectmen in late August claims that compliance limits Schiller now attains are not sufficient protection for Eliot residents. Selectmen asked that the EPA order the plant to discontinue its sulfur emissions, and a decision from the agency was expected, by law, within 90 days. The temporary shutdown of the federal government, however, delayed the process for six months, leaving the matter unresolved until May.

The petition to the EPA marks a relatively new strategy in disputes pitting states against one another. It has been employed successfully only one other time, in an action in which New Jersey faced off with Pennsylvania over sulfur dioxide pollution at a power plant in Portland in the Lehigh Valley, the historic center of many of the region’s slate quarries. The EPA ordered the Portland plant to reduce its sulfur dioxide emissions by 81 percent to resolve the cross-border pollution.

Eliot’s struggle with the effects of coal burning go back almost to the plant’s opening in 1949. Town residents have experienced the impact of air pollution – particularly evident in ash or soot floating in the air – for a half-century or more.

“People in Eliot have been complaining about this for 20 years,” said Brand. “These are the folks who are breathing the dirty air. For a long time they were complaining about the ash. That was the visible sign that something was wrong.”

But the focus on the sulfur dioxide emissions pinpoints the real problem, Brand said. “Coal is an outdated technology. It’s a filthy, dirty process that makes people sick.”

From the river’s waterfront, four stacks at Schiller can be clearly seen, but one is no longer used, Murray said. And they are hardly the only chimneys along the heavily industrial waterfront. The power-production process involves releases of sulfur dioxide and produces soot, ash and smoke, but Murray said his company is convinced it is not responsible for Eliot’s pollution problems.

“The role of Schiller coal boilers has changed over the years,” Murray said. While the company relied more on coal a generation, even a decade, ago, the coal boilers no longer operate all of the time.

“There’s lots of stacks (along the Piscataqua River) and a couple of bridges,” he said. Emissions from tens of thousands of cars, trucks and boats moving through the area every day, along with emissions from other industrial sources, contribute to the pollution problem.

“We believe the facts are on our side,” Murray said. “We have not violated air quality standards. The petition claims wrongly that we are in violation. We’ve done what we have to do, and we’re always looking for other things we could do, but at this time, we’re fully within all requirements that are before us.”

But many residents said they believe emissions from Schiller have had adverse health consequences, elevating levels of asthma and exacerbating other respiratory problems.

The health case is tough to prove, though, without hard, timely evidence, which does not exist. The most recent state data, compiled in May 2010 by the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the Maine Asthma Council, are based on 2009 findings and have not been updated for five years. The state’s statistics show a complicated asthma profile among Maine residents, one that is not easy to interpret in terms of causes or sources of pollution.

Maine does have the seventh highest asthma rates reported in the nation, with about 10 percent of the population afflicted with the disorder, compared to 7.8 percent nationally, according to the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The highest rates of asthma across Maine occur among children and minority populations – with 10.7 percent of children and 16.5 percent of the non-white population suffering from the breathing disorder.

But the most elevated rates are not in York County, where Eliot is located; they are farther north, according to state surveillance. And other areas – Aroostook, Down East and central Maine – report much higher rates of emergency room visits from asthma than York, which shows the lowest rates of emergency room visits in Maine – about a third of what Aroostook reported in 2009.

Furthermore, no actual air-quality data have been gathered in Eliot. The town’s petition relies on sophisticated computer modeling, which the EPA accepts as a valid method of measurement but Schiller contests. That modeling suggests that when the plant is running at full power – especially common in the dead of winter or in summer when demand for electricity peaks during stifling weather – the sulfur dioxide emitted from the stacks likely exceeds air-quality limits.

Eliot residents want the EPA to put any question about the source and severity of its pollution problems to rest, by conducting real-time data collection and establishing updated information on health problems associated with sulfur dioxide emissions.

“There’s just not enough hard data,” Richards said. “But there is enough speculative data to warrant looking into it.”

Like Richards, other Schiller detractors point to the incidence of certain health problems – including lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchitis and colds that linger with a raspy cough – as evidence of poor air quality in town.

But contradictory findings provide Schiller with what the company contends is a clear and strong defense against the Eliot petition, Murray said. Schiller has taken corrective action for problems in the past in which its emissions might have contributed, he said, attesting to the company’s willingness to be a good neighbor to the community.

For example, nearly 20 years ago, the problem of soot and ash that left homes, cars and pools fouled with a dark, cloudy residue seemed to many residents to come directly from the smokestacks. In response, the company went so far as to power wash homes and cars in an effort to correct the problem.

Eliot resident Ray Faulkner remembers how the company agreed to have black soot removed from his Maple Avenue home in the early 2000s.

“The power company has always been reactive, not proactive,” said Faulkner, an environmental specialist employed by Schiller from 1971 to 1987. His home is still streaked with residue from emissions today.

Another resident, who asked not to be identified, recalled how the outer walls of his mother’s house during much of the 1950s “looked like they had black measles all over them” because particles from the coal stacks drifted through town, pocking wood exteriors and coating parked cars with a dark film. Housewives who did laundry on days the Schiller stacks were cleared could count on having to do wash twice – once before the soot wafted through and a second time after laundry drying outdoors had effectively filtered ash from the air.

“Basically people had been resigned to the air pollution,” said Brand.

But that sense of powerlessness is changing – in and beyond Eliot.

In October, in Portsmouth, about 50 businesses and a handful of nonprofits called for the plant to be shut down.

While the most conspicuous problems are not as noticeable today as they were 20 to 25 years ago, many residents still worry about long-term health effects from exposure to air pollution that still darkens wood siding or remains floating in swimming pools on hot summer days when demand for electricity soars.

Schiller has publicized what it claims are millions of dollars of environmental improvements, beyond the conversion in 2006 of one boiler to burn clean wood chips. The company has installed electrostatic precipitators to remove ash particles and added selective non-catalytic reduction equipment to filter nitrogen oxide emissions.

And, company officials have said, the coal-burning boilers do not always run at full capacity, so the risks have been significantly reduced.

North Cairn can be contacted at 791-6325 or at:

ncairn@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.