Understanding and awareness of autism has come a long way in the last 30 years, but so much concerning the condition remains in the dark, even as diagnoses skyrocket.

That’s why it’s heartening to see a group of Maine-based researchers on the receiving end of a two-year, $1.2 million grant to study severe autism.

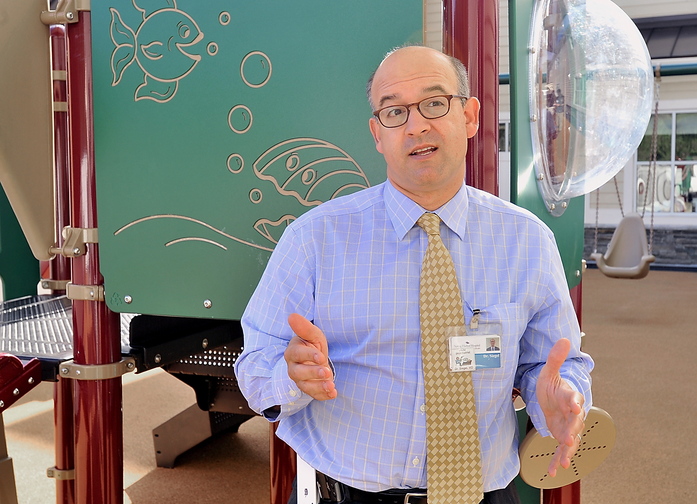

A team from Spring Harbor Hospital in Westbrook and the Maine Medical Center Research Institute in Scarborough, led by Dr. Matthew Siegel, will direct the study. It will track 500 to 1,000 children, with the goal of finding more effective treatment, and perhaps helping to determine a cause.

Research like Siegel’s is part of the answer to the questions raised by autism, the catch-all term for a wide-ranging disorder that is fast becoming one of the defining social health issues of our time. It requires a thoughtful response, as more than 500,000 children with autism will become adults in the next decade.

The numbers regarding autism are staggering. In 1984, fewer than 40 cases of autism were diagnosed in Maine. Today, there are about 2,300 cases. Nationally, one in 88 children – and one in 54 boys – has a diagnosis somewhere along the far-ranging autism disorder spectrum.

AGING OUT OF PROGRAMS

About 80 percent of Mainers diagnosed with autism are children. In the coming years, they will age out of the programs, services and support offered through school systems.

That is the dilemma facing doctors, researchers, schools, social service organizations, law enforcement and the public in the general.

“At some point,” Heidi Bowden, executive director of the Maine Autism Alliance, said Friday, “you are going to have a high number of them in the community.”

Education, then, is the most important part of the autism battle outside of the research lab.

Children with autism see the world in a different way, and their actions can be confusing to those unfamiliar with the disorder.

Many are nonverbal, and they become frustrated when trying to communicate.

Often they cannot filter out the world around them, and become overwhelmed at the sights, sounds and feelings bombarding them.

Students today need to understand autism and how it manifests in a person’s behavior.

As those students become adults, they will contribute to a society that doesn’t marginalize or dismiss people dealing with the disorder.

That is the goal behind the alliance’s Maine Schools Autism Awareness Project, a series of lessons coordinated with schools in April, National Autism Awareness Month. The group is now gearing up for its second year with the project.

“We are trying to move past awareness to understanding and acceptance,” said Bowden.

A similar challenge is faced by law enforcement.

According to the Autism Society of Maine, people with autism and other developmental disabilities are seven times more likely to come into contact with law enforcement.

Like mental illness, autism can lead to misunderstood interactions that unnecessarily escalate. Actions by people with autism can be seen as threatening or noncompliant, when in reality the person is just trying to process the situation. They might avoid eye contact or get too close to an officer. If officers are not properly trained, a situation can quickly turn tragic.

TRAINING POLICE

Matt Brown, a federal probation officer and the father of a teenage boy with autism, has conducted his autism and law enforcement program throughout Maine, as well as in other states.

The variety of agencies that have called on his expertise show the breadth of the issue.

Brown has trained police officers, game wardens, firefighters, emergency medical technicians, dispatchers, court officers and even airport security agents.

Wardens, who often are called to search for people with autism who have wandered off in rural areas, were early and enthusiastic adopters of the training, Brown said.

Courts, where dealing with victims, witnesses and defendants with autism is fraught with challenges, are behind, he said.

Even officers with full training, however, are susceptible to problems in the fog of an emergency, especially if they don’t know who they are dealing with.

That is why Brown is championing an effort to have parents of children with autism provide information to law enforcement. In the event of an emergency, dispatchers can notify responding officers that autism may be a factor, so that the officer has a full understanding of the situation.

That is just one creative solution in an issue that requires many.

Send questions/comments to the editors.