A proposal to cut the physics major at the University of Southern Maine surprised many, but it’s just the latest piece of a three-year-old systemwide effort to closely scrutinize any degree program with fewer than five graduates a year.

A dozen majors have already been suspended or eliminated systemwide, and USM’s top academic officer said Friday that another 16 programs there — aside from physics — are still up for future review.

The same kind of cuts are happening at other state university systems around the country. In Maine, system officials say cutting programs that are no longer relevant or well attended increases faculty efficiency and frees up resources to add programs and courses that address workforce needs, such as new programs in tourism and sports management, and attract nontraditional students.

That doesn’t mean changing the University of Maine System’s traditional liberal arts education mission, according to board of trustees Chairman Sam Collins.

“Our focus has changed. Our mission has stayed the same,” Collins said. “We need to find savings anywhere that we can so we can keep the education affordable and still be delivering a quality product.”

The system is facing an array of negative factors: a stubbornly depressed economy, flat funding from the state, increasing competition from both public and private education providers, and declining enrollments. All that, Collins said, means the university system must adapt to these changing circumstances, and quickly.

“There needs to be a sense of urgency in the entire system,” Collins said. “We cannot continue to deliver education in the same fashion that we have in the last 100 years.”

That was the thinking behind the trustees’ decision three years ago to tell each campus to closely examine underenrolled programs — with an eye to either grow or eliminate them — in addition to applying the same scrutiny to any class with fewer than 12 students.

“It’s a common scenario that’s playing out all over the country,” said Susan Hunter, who oversaw the 5-12 process at University of Maine in Orono as vice president for academic affairs and provost. Currently, she is vice chancellor for academic affairs for all seven universities in the University of Maine System. “The scale and scope and magnitude, painful though it was, was less painful and less draconian than in many states.”

Headlines around the nation paint a bleak picture of sweeping cuts to degree programs at state-run universities, almost all of them failing to meet target enrollments of at least five or six graduates per year. In the past four years, Pennsylvania’s state university system cut 160 programs; Louisiana cut 50 degrees.

The recession triggered many of the cuts, according to a report earlier this year from the Washington D.C.-based Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Among the cuts cited in that report: The University of California system consolidated or eliminated more than 180 programs; Arizona consolidated or eliminated 182 colleges, schools, programs and departments; the University System of Louisiana cut 217 academic programs and the University of Nevada-Las Vegas cut 31 degree programs.

The cuts have sparked a nationwide discussion over the fate of the traditional liberal arts education in college, because many cuts have been to language and arts programs, while demand has increased for programs narrowly focused on quickly attaining a specific post-graduation career. Collins and other University of Maine System officials insist they are committed to continuing to offer a broad-based education that serves students in an array of fields and careers. Balancing that goal, while addressing the financial realities, is the challenge facing everyone, Collins said.

“The 5-12 plan is a trigger, and when (a program or class) drops below what is economically feasible to deliver, then we have to look at that program and look at how critical it is to the mission of the university and how relevant it is,” Collins said. “For each campus, it’s different because each mission is different.”

The trustees take a largely hands-off role at the campus level, he said, and base their decisions on recommendations from the individual campus presidents and provosts.

“It’s up to the president and provost to determine whether (a program) should be eliminated or suspended,” he said. “Are you going to get it right every time? Probably not. But we closely analyze it.”

He said some programs that have been eliminated could be brought back in the future, if the need arose. At least one major — theater at the University of Maine — was brought back after being put on suspension in 2011, but most suspended programs are targeted for elimination.

Department heads with underenrolled programs provide written reviews of the program to make the case for why it should be preserved or suspended.

The years-long process is now poised to take a big step forward.

In her new job, Hunter is tasked with the first-ever comprehensive review of all academic programs across the seven universities, with a goal of eliminating redundancy and coordinating program growth and development. It’s a natural step in the wake of the individual reviews that have been under way at each campus.

“This could be a very exciting venture and could lead us in a very positive direction,” Hunter said.

COMBINING FORCES

USM Provost Michael Stevenson, who started his job last year midway through the USM program review process, said he plans to work with science faculty in several underenrolled programs to come up with a solution together. In addition to physics, several other undergraduate majors in the College of Science, Technology and Health have fewer than five graduates a year, including chemistry, geoscience and environmental science.

At this stage, the faculty should be thinking of ways to collaborate with each other, or with other science departments at Orono or elsewhere in the system, to create a more robust major or program, Stevenson said. Working with Hunter would be part of that process, he said.

“What has to now happen is a broader conversation across the sciences,” he said. “That (planning) requires some deep thinking that goes beyond any small interdisciplinary group.”

Critics have questioned whether cutting some programs makes sense, in particular science degrees at a time when state and education officials are emphasizing the importance of science, technology, engineering and math careers, or STEM disciplines, to economic growth. Those cuts may make a university less attractive to certain students or parents, they say.

“It is a bit of a trade-off,” Hunter said. “You have to be upfront about what is potentially suspended, and certainly some people were disappointed.”

But she pointed out that many of the classes in the affected areas remain, even if the major is cut. “It’s not draconian,” she said.

At Orono, majors in wood science and technology, aquaculture and forest ecosystem science have been suspended and are targeted for elimination, despite the fact that northern Maine is known for its fishing and lumber industries. Those majors are being folded into similar majors in the department.

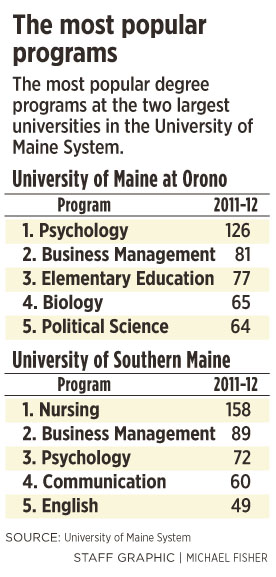

The campuses are adding courses and majors at the same time, to meet workforce needs in today’s economy and responding to interest from students, Hunter said. In recent years, for example, nursing programs have expanded, and USM added sports management and tourism and hospitality degree programs.

DECISION TIME

Although the mandate to cut costs came from the trustees, the individual campuses decided how to make the necessary cuts.

As the flagship campus, with the largest numbers of students, the University of Maine in Orono faced the most sweeping changes. Then-President Robert Kennedy asked the deans of the schools’ five colleges to come up with a plan to cut 20 percent, then formed a working group to make recommendations based on those plans and input from Hunter.

After seven months, the group announced a plan to eliminate 16 majors, including theater, several foreign languages, music and women’s studies. At the time, a news release from the University of Maine anticipated that the changes would result in a $12.5 million savings between 2011 and 2014.

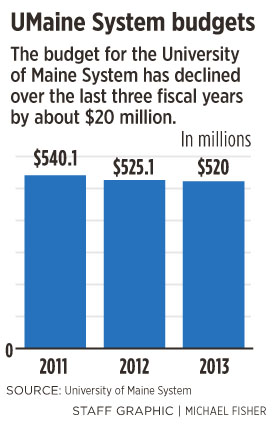

Rebecca Wyke, vice chancellor for finance and administration for the system, said those figures were high, and that the goal was closer to about $2 million a year systemwide. Wyke did not have figures for how much money the system has saved so far, saying it was difficult to calculate. Overall, however, the system has reduced the size of its budget in recent years from $540 million in 2011 to $520 million in 2013.

During that same period, the state allocation has been flat-funded at about $177 million a year, and tuition has been frozen for two years.

Eliminating some programs while adding others is an important part of a larger effort to lower costs and increase revenue, Wyke said.

“Healthy programs should not fear review,” she said. “We need to be more competitive and aggressive across the board, not just in program review.”

At the University of Southern Maine, the second-largest university in the system, a similar process was undertaken, culminating with a 2011 report from then-Provost John Wright. Today, that work has been picked up by Stevenson, but the financial picture has since deteriorated, he said.

In addition to flat state funding, dwindling enrollment has been particularly bad at USM. Systemwide, enrollment is off by almost 3 percent from a year ago; at USM, that figure is more than 8 percent.

With that in mind, Stevenson said he is not following the recommendations from the previous provost, which, for example, recommended that USM should “invest” more resources in the physics department, rather than cut the major entirely.

Programs recommended to be sustained in that report will remain for now, he said. They will be reviewed on their usual seven-year cycle for accreditation. Programs recommended for investment, elimination or further consideration are now on the list to be reviewed immediately, he said. The effort started with physics, because that program recently completed a department review, and Stevenson plans to meet with faculty from geoscience and women and gender studies next.

“I think one might conclude that that process wasn’t entirely successful,” said Stevenson, noting that USM is currently trying to identify $5 million to cut by the end of the 2013-14 fiscal year, after already cutting $5 million in 2012-13. “We took that as far as we could take it and now we have to have a finer-grained conversation.”

By mid-spring 2014, Stevenson said he needs to work out “the financial aspect” of the program changes. “It’s a very tight deadline,” he said.

‘IT WAS SHOCKING’

Still, the decision to cut physics has rankled faculty, students and members of the community, who have written letters in support of keeping the program.

“It was shocking,” Physics Chairman Jerry LaSala said about learning that the major might be cut. “Everyone believed the process was essentially done. We knew there was likely to be some revising of it, but the idea that there would be wholesale shutting down of majors without consultation was not on anyone’s mind.”

Still, he thinks the degree will remain.

“We’ve gone through this before and we’ve survived,” he said. “We have a nation and a university system that says they are dedicated to science and technology and engineering education, and shutting down a viable physics major for phantom cost savings is not a good way to do that.”

On Friday, the USM Faculty Senate discussed the physics situation, and voted 31-0 that the administration either withdraw the plan to eliminate physics and adopt the previous plan to invest, or begin the evaluation process anew, according to LaSala, who is also the Faculty Senate chairman. Under USM governance rules, he said, that vote triggers a process whereby the provost either agrees, or USM President Theodora Kalikow must respond to the Senate in writing why the administration does not agree, which could result in joint meetings to discuss how to move forward.

These kinds of cuts, referred to as program prioritization or program evaluation, have been a nationwide phenomenon for more than a decade, according to Robert C. Dickeson, a higher-education consultant and president emeritus of the University of Northern Colorado. The key is making the cuts strategically.

“You can’t cut programs to prosperity. It is a means to reconcile a budget,” Dickeson said. Schools must also make new investments and add programs, he said.

“The thing is, we are trying to do too much, we are trying to be all things to all people,” he said of universities. “In the business world, if there’s a product on the shelf and it isn’t selling, we get rid of the damn thing.”

That process doesn’t come easy in academia, he said, and he praised Maine education officials for their efforts.

“I’m delighted they’re doing it. I hope they do it well,” he said. “Many that do it well find themselves stronger, and it’s the best thing they’ve ever done. There are also horror stories of (schools) that didn’t follow the rules and wound up in major crisis situations.”

The physics situation at USM is still attracting high-profile attention. Maine Senate President Justin Alfond, D-Portland, said the Greater Portland state legislative delegation and members of the Legislature’s Education Committee are meeting with President Kalikow on Friday to discuss the future of the physics degree program.

“We want to hear first-hand what the plan is,” Alfond said. From his perspective, the Legislature doesn’t want to micromanage these kinds of decisions, but it does have a hand in funding the higher education system.

“We’ve done our best to hold our investments flat” instead of cutting the state appropriation, he said. “But if we’re going to be competitive, we have to be laser focused on our investment in higher education.”

“We need to do more to brand our University of Maine System so that everyone around the country and around the world knows that we’re great at ‘X’ program or ‘Y’ program. That’s the work we need to do,” Alfond said.

Noel K. Gallagher can be contacted at 791-6387 or at:

ngallagher@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.