In Maine’s long history, three days stand out above all others: July first, second and third of 1863.

The three days of the Battle of Gettysburg.

One hundred and fifty years ago this week, in the Civil War’s greatest battle – the outcome of which changed the course of the war – Maine regiments played a critical role in turning back the Confederate invasion of the North and preventing what would have been a catastrophic loss for the Union.

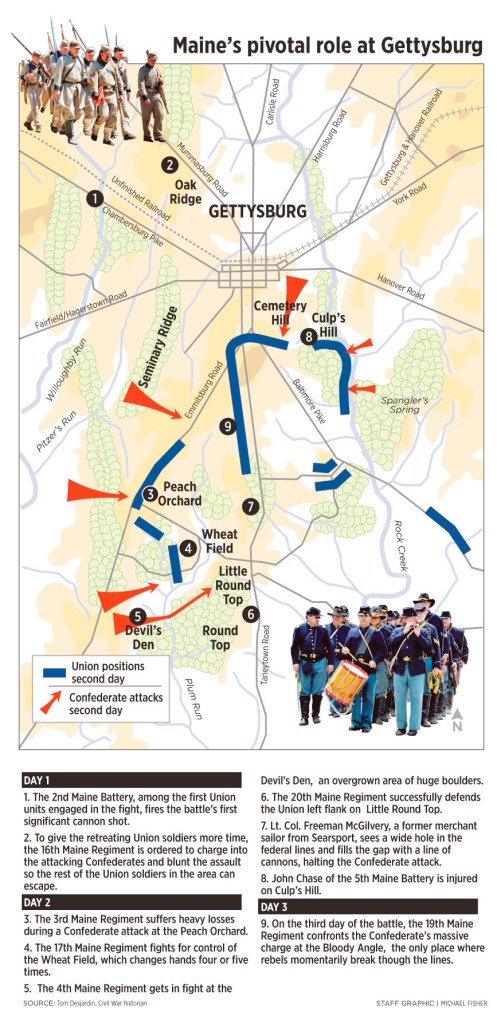

On every day of the battle, from the first cannon fire in the hills outside Gettysburg to the Confederate Army’s massive frontal attack on the third day, Mainers were in the middle. They were at all the bucolic landmarks made famous by bloodshed: the Devil’s Den, the Peach Orchard, the Wheat Field, Little Round Top, the Copse of Trees, the Bloody Angle, Cemetery Hill.

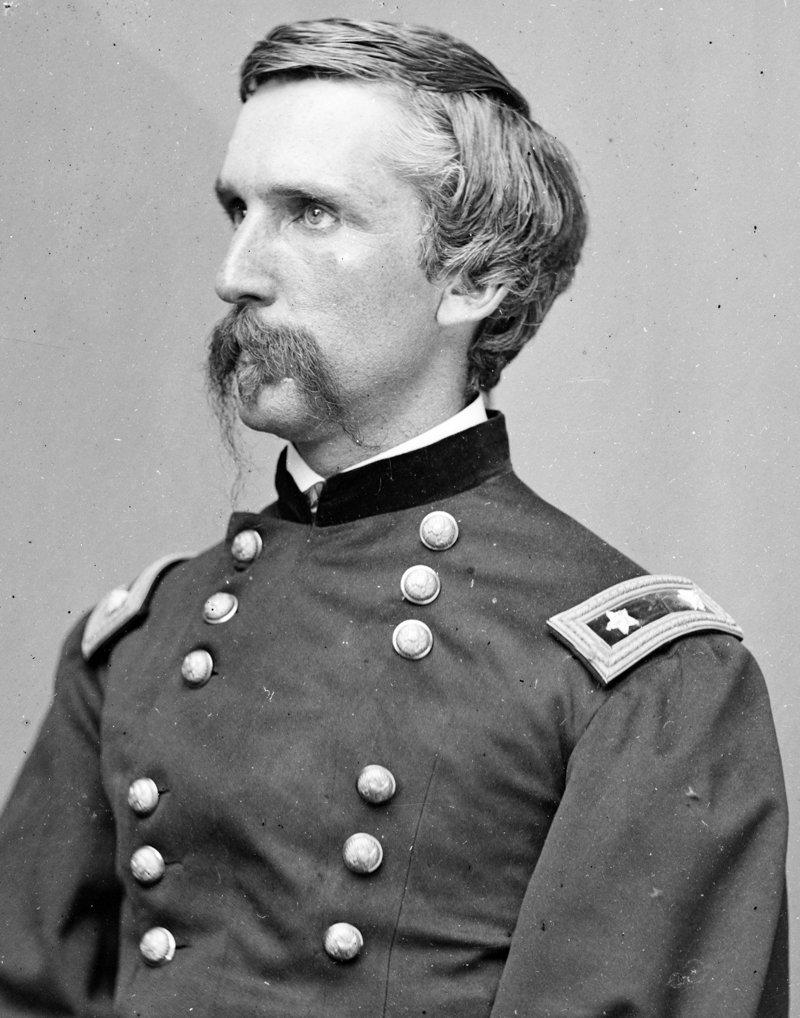

The exploits of the 20th Maine Regiment, which defended Little Round Top under Bowdoin professor Joshua Chamberlain, have been celebrated in books and on film, but other Maine regiments played roles that were just as critical, said John Heiser, a historian at the Gettysburg National Military Park.

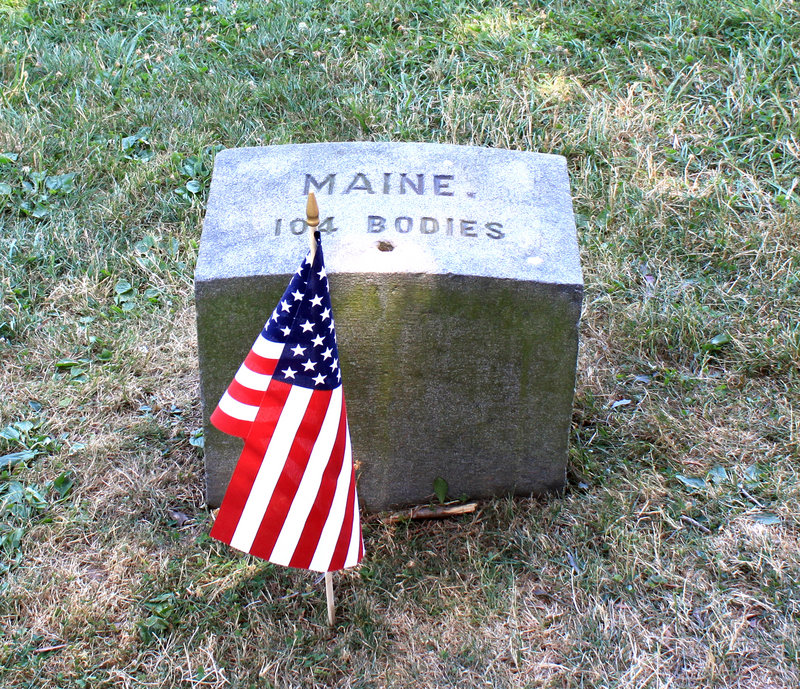

While more Union soldiers from New York and Pennsylvania fought and died at Gettysburg, Mainers sustained heavy casualties – one in four of the nearly 4,000 Maine soldiers engaged at Gettysburg was killed, wounded, missing or captured. And they fought at the battle’s key strategic points, Heiser said.

“This is really a Maine battlefield more than anything else.”

MAINERS RESPOND

Before the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, most Mainers opposed the idea of entering into armed conflict with the South, said Tom Desjardin, a historian for the Maine Bureau of Parks & Lands and the author of several books on the Civil War. Many families along the Maine coast had invested in ships involved in trade with the South, and they knew that war would be disastrous for Maine’s merchant fleet.

But when war came, so many Maine men enlisted that the state would contribute a larger number of soldiers in proportion to its population than any other state in the Union.

In all, about 70,000 Maine men were drafted or volunteered – 59 percent of eligible men ages 18 to 45.

“They didn’t want the war to happen, but when it started they went in great numbers,” Desjardin said.

By 1863, though, many Northerners had grown weary of the war. The Union army in the East had never won a clear victory. Its leaders were no match for the Confederacy’s generals, particularly its commander, Robert E. Lee.

In early June, Lee moved his army of 70,000 men northward to invade Pennsylvania, where he hoped that a decisive battle on Union soil would encourage Northerners who opposed the war to push for peace and convince France and Great Britain to recognize the Confederate States of America as an independent nation.

Under their new commander, Maj. Gen. George Meade, the 90,000 men in the Army of the Potomac moved northward to check Lee’s advance. The two armies had only a vague idea of each other’s position. Meade tried to place his troops between Lee’s army and the cities of Baltimore and Washington, while Lee looked for the right ground for a winner-take-all battle that would end the war.

The two great armies bumped into each other near a Pennsylvania town, Gettysburg, population 2,400. Ten roads converged on the town from all directions, as did the two armies.

Over the next three days, 8,000 were left dead on the field, and 4,000 died shortly after from injuries suffered in the battle.

DAY ONE

The battle opens with a minor skirmish on a ridge a mile and a half west of Gettysburg, as the outer edge of the Confederate Army marches toward the town and is met by a smaller number of Federal troops.

Most of the Union Army is stretched miles southward from Gettysburg, and the objective of the first Federal soldiers at Gettysburg is to stall the Confederate advance and give the rest of the Union Army time to arrive, Desjardin said.

The 2nd Maine Battery, among the first Union units engaged in the fight, fires the battle’s first significant cannon shot at 10:45 a.m.

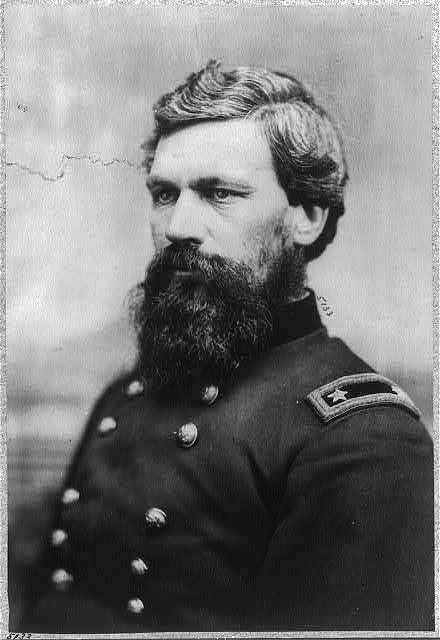

Maj. Gen. Oliver Howard arrives to take command. Howard, from Leeds, Maine, attended North Yarmouth Academy and Bowdoin College. He is an amputee, having lost his right arm a year before after he’d been shot during a battle in Virginia.

Deeply religious, he had contemplated becoming a minister before the war broke out. That day, Howard makes a decision that will later prove to give the Federals a significant strategic advantage.

He sends a brigade to occupy Cemetery Hill, recognizing that the high ground south of town provides the best defensive position in the area. Over the course of the three-day battle, thousands of soldiers will be killed trying to take the hill or defend it.

On the first day, the fighting grows more fierce as both armies pour into Gettsyburg. The Confederates push back the Federal troops, who retreat through the town and dig into the hills south of town, from Culp’s Hill to Cemetery Hill.

To give the retreating Union soldiers more time, the 16th Maine Voluntary Infantry Regiment is ordered to charge into the attacking Confederate troops and blunt the assault long enough for the rest of the Union soldiers in the area to escape. It is a suicide mission.

Of 275 soldiers from the 16th Maine engaged that day, 11 are killed, 62 wounded and 159 captured, a casualty rate of 84 percent.

Just before they’re captured, the men tear up the regiment’s silk flags and hide the shreds in their clothing, preventing the Confederates from seizing their colors as a prize of war.

“We were sacrificed to steady the retreat,” Capt. Abner Small of Waterville said in a written account of the regiment’s actions that day. Small was one of the few soldiers in the regiment to escape.

DAY TWO

During the night, thousands of soldiers from each side arrive, and by morning 50,000 Confederates and 60,000 Union troops are eyeballing one another across an open field. The second day of the battle is essentially a massive Confederate attack on the Union left. The Confederates nearly break the Union line, but a Maine unit at every key point plays a pivotal role holding them back, Desjardin said.

At the Devil’s Den – a rugged, overgrown area of huge boulders at the base of a ridge – there’s a wild fight, with men stabbing each other with bayonets or shooting muzzle-to-muzzle. Here the 4th Maine is fighting, along with troops from New York, Pennsylvania and Indiana.

Nearby at the Peach Orchard, the 3rd Maine finds itself in a similar brawl, with 58 percent of the regiment missing, captured or dead.

At the Wheat Field, the 17th Maine suffers heavy losses as the field changes hands four or five times.

The Confederates gain ground and push forward. A gap opens up in the Union lines, and the rebels have a chance to break through at the Union Army’s weakest point, capture a key road and divide the Union Army in half. The Confederates now have the greatest chance of winning the battle and turning the course of the war in their favor, Desjardin said.

Standing on Cemetery Ridge, Lt. Col. Freeman McGilvery, a former merchant sailor from Searsport, sees a wide hole in the Federal lines. Without any infantry support, he grabs all the artillery he can find and patches together a line of cannons and halts the Confederate attack.

Around the same time, Federal troops are arriving at Little Round Top, a hill on the left side of the Union position. On the far left side – at the very end of the Union line – stand 358 infantrymen with the 20th Maine, with their new commander, Col. Joshua Chamberlain, who before the war was a professor of rhetoric at Bowdoin College.

If the 20th Maine retreats here, the entire Union line would be flanked and exposed. Chamberlain is ordered to hold the hill “at all hazards,” a military phrase that means a fight to the death.

Almost immediately, Confederate troops charge up the slope, and Mainers fire back.

The last man at the far extreme of the entire Union line is Sgt. Abner Hiscock, 27, a mechanic from Damariscotta, whose arm is soon shattered by a mini-ball. His commander is Capt. Ellis Spear, a teacher from Wiscasset.

Alerted that the rebels seem to be extending their line toward the regiment’s left in an attempt to go around its flank, Chamberlain orders his left wing to drop back, creating a formation like the letter V, making it easier to defend a side attack.

When the Confederates attack a third time, the 20th Maine’s center crumbles. Color Sgt. Andrew Tozier, 25, from Plymouth, stands in the center. Remaining upright while holding the flag staff in the hollow of his shoulder, he fires back using a musket and cartridge box from a wounded comrade.

“Tozier was fighting his own private war,” Chamberlain would later recall.

The Union ranks eventually reform. With their ammunition almost out, Chamberlain decides to fix bayonets and charge down the hill, with the left side wheeling to the right as in a gate swinging shut. Tozier, flag in hand, is at the center of the charge, serving as a linchpin as the gate swings around. Chamberlain runs beside him.

The surprised Confederates turn and run, and nearly 200 are captured.

Chamberlain and Tozier would be awarded the Medal of Honor.

If the rebels had taken the hill that day, they could have rolled up the Union lines from the side and won the battle, said Sen. Angus King, a Maine independent, who on Wednesday delivered a 13-minute description of the battle on the Senate floor. King said a Union defeat could have led the North to negotiate a peace that allowed the nation to break apart.

The volunteer soldiers from Maine, he said, made the difference.

“It’s arguable that they saved the country.”

DAY THREE

On the last day of the battle, Lee tries to break through the Union lines by launching a massive frontal assault aimed its very center. Following a thunderous, two-hour duel of artillery batteries, 12,500 rebel soldiers, forming a line almost a mile wide, march over a field toward the Union line. A clump of trees on Cemetery Ridge serves as their target landmark. Here is the 19th Maine. And this place, the only spot where Confederate troops momentarily break though the lines, will become known as the Bloody Angle for the intensity of the fighting.

The 19th Maine, which had 405 men at the start of the battle, had 206 by the end of the third day. Most of its losses occur in the 15-minute fight at the Bloody Angle.

The Confederate losses are staggering. Lee gathers what’s left of his army and leads them back to Virginia.

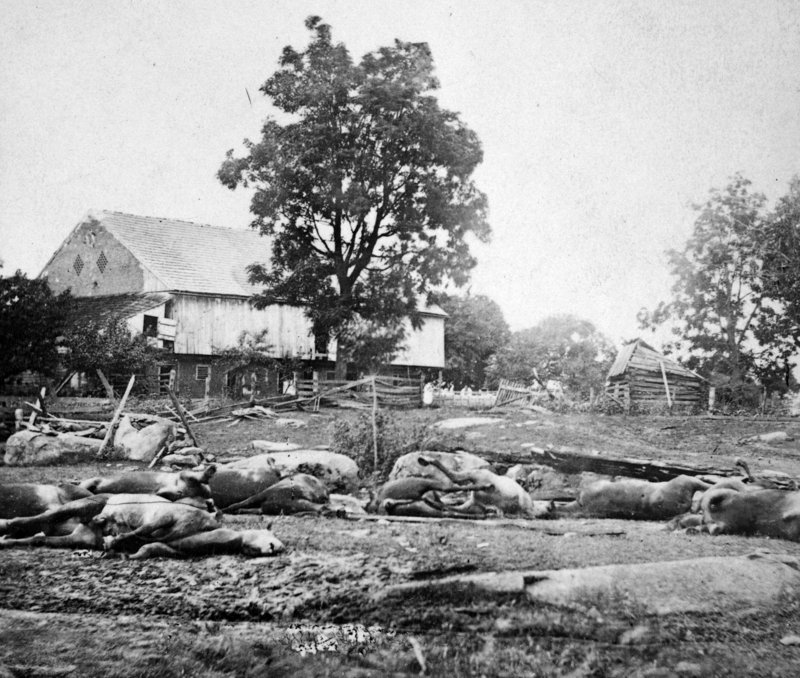

The fields and hills around Gettybsurg are littered with dead soldiers and horses.

In a letter to his brother written on July 5, Capt. William Livermore, from Milo, a color guard with the 20th Maine, describes the landscape near the former Confederate lines after the battle: “There was as many as 30 or 40 lay dead there of that (regiment). They had laid there 3 days in hot July weather and I wish I never could see another such a sight. It is nothing to see men that have just been killed. But every man was swollen as large as two men and purple and black.”

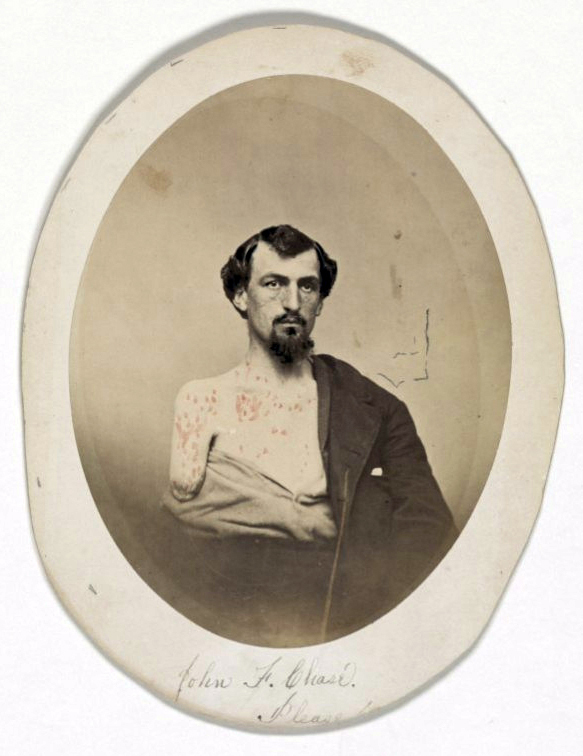

The body of John Chase, 19, from Augusta, is tossed into a wagon filled with dead soldiers. On July 2, while stationed with the 5th Maine Battery on Culp’s Hill, he had been hit by 48 fragments of a shell that burst four feet away from him. The shell tore off his right arm, put out his left eye, and pierced his lungs. He is then left for dead on the field.

As the wagon bumps along the road toward the newly dug graves, Chase moans.

The driver pulls Chase from the pile of bodies and gives him a sip of water. Chase mumbles his first words. He asks, “Did we win the battle?”

Tom Bell can be contacted at 791-6369 or at:

tbell@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.