Eric Weinrich remembers when his legs felt so heavy from fatigue, he struggled to swing them over the hockey arena sideboards and return to the ice. When his brain was so tired, it worked instinctively.

He remembers the pure joy of winning and the sharp heartbreak of losing. The star defenseman at North Yarmouth Academy and the University of Maine played 81 games of playoff hockey during 17 seasons in the NHL. Weinrich won’t say he’s reliving his own career when he watches the Boston Bruins and Chicago Blackhawks play this final series for professional hockey’s biggest prize.

He can say he knows what pushes men to test themselves in extraordinary ways while chasing the chance to hold aloft the Stanley Cup, something he was never able to do.

“Sometimes I wonder,” said Weinrich, 46. “Would I have traded all those seasons, all my experiences, for one season and the Stanley Cup? That would be a tough one to answer.”

He intends to watch Monday night’s Game 6 from his home in Yarmouth. The Blackhawks, after winning Game 5 in Chicago on Saturday, can take the best-of-seven series with one more victory at TD Garden in Boston. A Bruins win would send the series back to Chicago for Game 7 on Wednesday.

Weinrich knows both cities well. As a younger man, he played five seasons with the Blackhawks, beginning in 1993. Eight years later he was traded to the Bruins for part of one season.

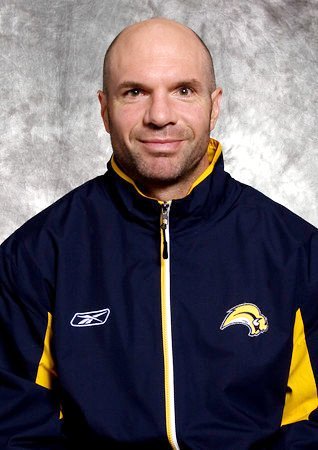

“I have friends on either team but no allegiances,” said Weinrich, who is a pro scout for the Buffalo Sabres. “I’m just a fan.”

That’s true, but not accurate. He was introduced to hockey when his father brought him to a frozen pond near their home in the Kennebec County town of Gardiner some 40 years ago. Weinrich may be retired, but he’s a hockey player, an NHL lifer. The intensity of playoff hockey that we see but can only imagine, Weinrich knows.

He was a defenseman’s defenseman when he played in the NHL, blocking two shots with his stick or body for every one he scored. He wasn’t a big talker or a fighter. He was a standup guy, accepting responsibility. An English major at UMaine, he always could take in the larger world around him.

He watched a trainer tape Ken Daneyko’s stick to his glove after Daneyko broke his hand and refused to come out of a playoff game. Daneyko and Weinrich were teammates with the New Jersey Devils in the late 1980s, and that moment wasn’t lost on Weinrich.

He knows the wear and tear on bodies that have been hit countless times and knocked down often since the season began. Muscles that cry from fatigue and cuts and bruises that bleed. The exhaustion that comes from simply telling your body to do more again and again because it’s the playoffs.

Yes, Weinrich can call himself a fan, but fans don’t have his understanding of a brutally intense game.

“For these guys to be so close, one win away from winning the Stanley Cup, I can’t even imagine,” said Weinrich. “When you get to this point, you’re almost numb. Everything, except for game time, seems like you’re in a fog. You save all your energy for the game.”

Many playoff games go into an overtime period. Or a second overtime. Or a third. Weinrich remembers his own marathons. “It’s survival,” he said. “You’re tired. You have to use all your senses, knowing where your guys are and where their guys are. What helps is knowing they’re feeling it just like you.

“One of the things that gets lost in the fury of the game is how you start doing so many things instinctively. I’m a defenseman. Someone dumps the puck in my end and I’ll take a look over my shoulder without thinking and know exactly who’s behind me, where, and what I’m going to do. You practice these things over and over and over and this is where it’s helping you most.”

Then there’s the crowd. Blackhawks fans are just as boisterous as Bruins fans. Weinrich played in Chicago Stadium, before it was demolished in 1995. Madhouse on Madison, it was called. When the largest pipe organ in the world (more than 3,000 pipes) sounded the first notes of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the crowd would erupt.

“Boston is loud, but in Chicago it was like nothing you’ve ever experienced,” he said. “You couldn’t hear the guy singing. My body was shaking at the end. It was hard to keep your composure; it didn’t hurt your adrenaline level at all.”

The crowd has been just as noisy in the new arena, the United Center. Nonstop noise. Even casual fans don’t need to be told what’s at stake when they tune in playoff games in Chicago or Boston. The noise tells the story. It follows what sometimes seems like long, uninterrupted minutes of play. This isn’t baseball or football or even basketball with their constant stoppages.

“I love the fact the games are so spontaneous,” said Weinrich.

His Blackhawks reached the Western Conference finals in the 1994-95 season before losing to the Detroit Red Wings in five games. Three of Detroit’s four wins came in overtime. Conference winners move on to the Stanley Cup finals. It was the closest Weinrich would get to the prize.

He knows the joy of being on winning teams in the playoffs. “It’s an amazing feeling to win a series,” he said. “It gives you a feeling of being a little more invincible. I know what I’ve done and I’ve just got to keep it going.

“To lose, it’s really heartbreaking. You’re in disbelief it’s over. It’s devastating. You play all season just for this chance. You’re pretty drained. You really can’t think of anything.

“You look around the locker room. All of us have been fighting for each other. It’s a bond. It’s more than a game.”

It’s the Stanley Cup playoffs.

Steve Solloway can be contacted at 791-6412 or at:

ssolloway@pressherald.com

Twitter: SteveSolloway

Send questions/comments to the editors.