Mark Bessire first became interested in African art while working as a graduate student in New York City.

The year was 1984, and the Museum of Modern Art mounted an exhibition titled “Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern.”

It proved hugely controversial, because its curators put forth the notion that traditional African art shared a spiritual and aesthetic bond with modern Western art. The museum was accused of wrenching the African works from their social contexts in a blatant example of colonial imperialism.

A decade later and newly married, Bessire and his bride, Aimee, found themselves in the African country of Tanzania. Bessire was working at a museum there, enjoying the benefit of a Fulbright scholarship. Aimee was working on her doctoral degree at Harvard, studying the Sukuma culture of Tanzania.

Almost two decades later, Bessire brings that hard-won knowledge to bear in the Portland Museum of Art’s latest exhibition, “Shangaa: Art of Tanzania.” It includes more than 160 objects, most of them sculptural, that have rarely been seen outside Africa or Europe.

The exhibition opens Saturday on the museum’s third floor, and will remain on view through Aug 25.

For a museum that generally dedicates its summers to familiar art from Maine and the Americas, the Portland museum takes a bit of a leap with “Shangaa.”

Granted, the William S. Paley Collection, featuring the very best of European Modernism currently on view on the museum’s first floor, satisfies the summer blockbuster requirement. Still, “Shangaa” marks a bold programming decision for Bessire and his staff, and provides a well-timed, if unlikely, complement to the Paley show.

“Certainly, there’s a lot of scholarship associated with this show, but we are presenting objects with broad appeal,” Bessire said. “Tanzania worked out because it was in my wheelhouse, but we feel it’s important to bring non-Western art to the museum. As the diversity of our community is changing, we want to be certain our museum is seen as everybody’s museum.”

Bessire is not credited as curator for this exhibition. That honor falls to Gary van Wyk, an African art scholar.

But Mark and Aimee Bessire both go deep with van Wyk. He is a family friend whom they met as college students, and they have a mutual interest in Africa and African art.

When he began plotting this exhibition, van Wyk contacted the Bessires for their advice and input. He acknowledged them for their help in his introduction to the catalog that accompanies the show, and Aimee Bessire contributed an essay about the Sukuma culture.

In Swahili, the word “shangaa” means to surprise or amaze. And this show is full of amazement.

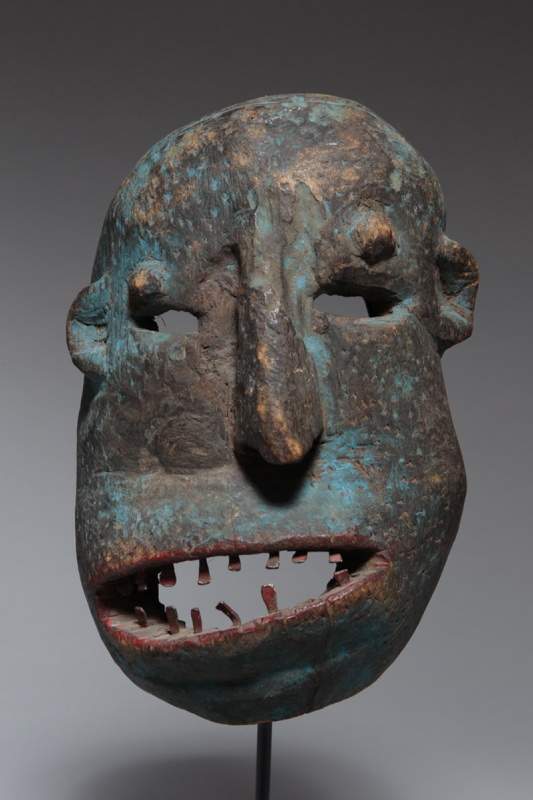

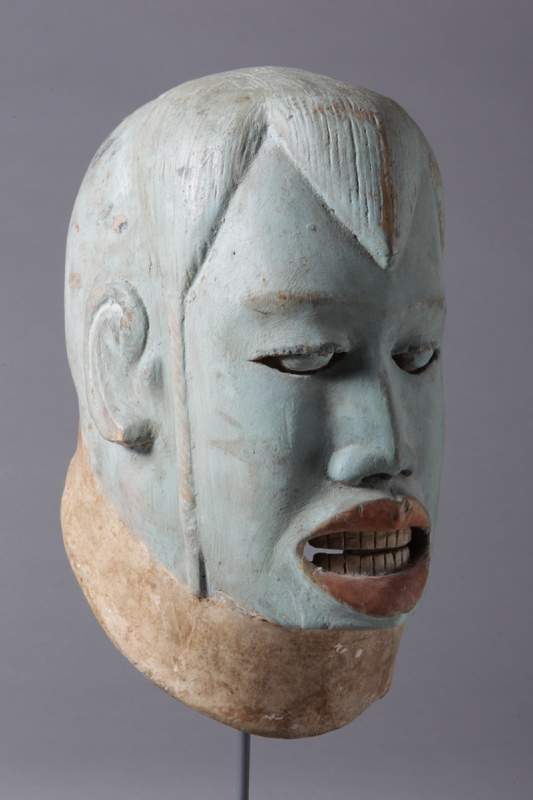

It includes mostly wooden carved and assembled objects, some with leather, metal, animal fur and other complementary materials.

There are domestic and personal items such as hairpins and tall house posts, as well as masks, figurines and other objects used in ceremonial dances and community celebrations.

Most of the objects date to the mid-1800s to early 1900s – not ancient compared to Greek standards, but old enough to be considered valuable and rare.

They are rarely seen, because art from Tanzania is not often circulated. Generally, most of the African art that Westerners are exposed to comes from the eastern part of the continent.

And while Tanzania is an east-African country and a former German colony, the Sukuma culture where most of these objects are rooted is in the western part of the country, far from the eastern coast.

“The art and culture from this part of the world has been neglected,” Bessire said, noting that this same exhibition was seen in New York before coming to Maine.

As the PMA exhibition suggests, the Bessires’ interest in Tanzania did not abate with their return to the states. Indeed, when he directed the Institute for Contemporary Art at Maine College of Art, Bessire showed contemporary African photography.

The couple has also adopted a Tanzanian effort close to their hearts. They began a project, Africa Schoolhouse, which is dedicated to helping children in remote parts of Africa gain access to life-changing education. Aimee is co-founder and director of the project, and travels to Tanzania several times a year for its work.

As museum director, Mark has less time for travel. But the couple and their children have made two family trips in recent years.

It is on that level that “Shangaa” feels deeply personal for Bessire.

He hopes his interest in this art and the culture of Tanzania reaches the community at large.

“I never want our museum to be predictable,” he said. “Aimee and I have worked over there, and it’s familiar territory for us.

“But it’s a wild card for the museum. We want people to walk in and say, ‘I wasn’t expecting this. But wow.’ “

Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.