Maine may be on the verge of a rapid, historic shift from oil to natural gas as a source of energy for generating electricity and heating homes and businesses.

It’s a transition that echoes the mid-20th century. In 1940, eight in 10 Maine homes were heated with wood or coal. Just 20 years later, 80 percent had moved to oil heat, U.S. Census figures show.

But in Maine’s rush to gas, it’s possible that some important issues aren’t being fully examined.

Is it wise for Maine to trade dependency on one fuel for another?

Is it a good idea to be so reliant on natural gas for electricity?

Will cheap gas kill more-costly renewable power, namely electricity from wind, which has the potential to become a major industry in the state?

Oil became dominant a half-century ago because it was cheap and, compared to wood and coal, cleaner and more convenient. Today, natural gas heat is the fuel of choice because it’s roughly half the cost of oil. That means a typical home that spends $3,000 with an oil furnace could heat for $1,500 with a modern gas boiler. And while all energy prices fluctuate, many experts expect that relative relationship to persist for the foreseeable future.

That forecast, coupled with the price volatility of heating oil, has led to a scramble in Maine this spring to catch up with the rest of the country, and ease a burden that’s costing the state hundreds of millions of dollars a year. Half of the homes in the United States already heat with gas, compared to roughly 5 percent in Maine. But that likely will change in the next few years.

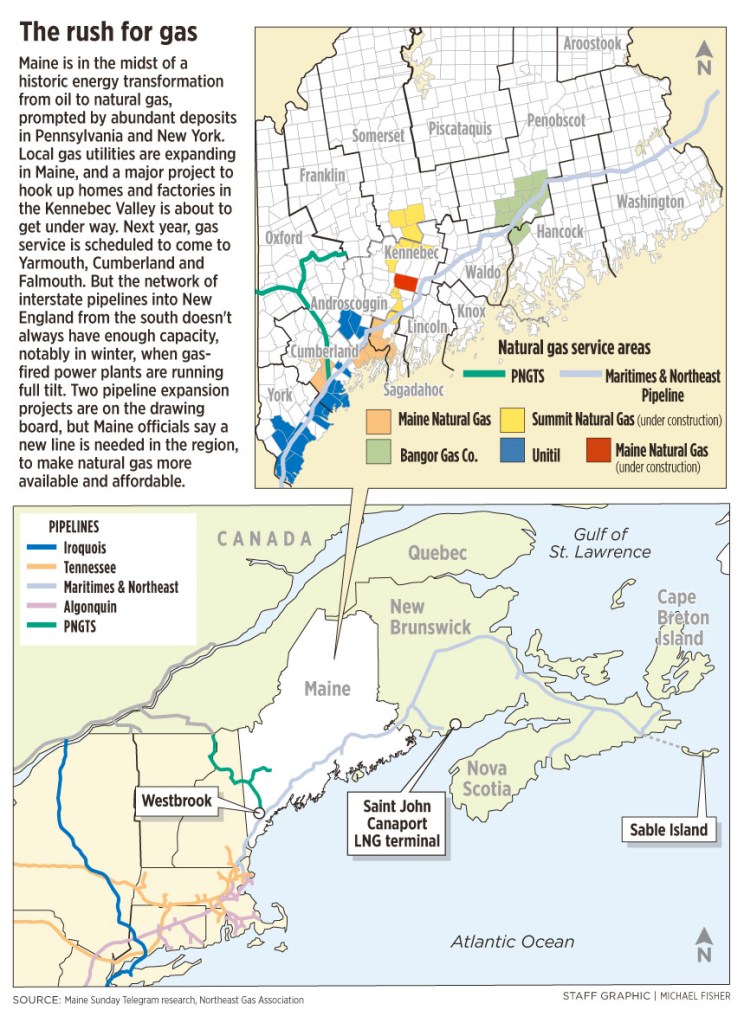

• In the Kennebec Valley, Summit Natural Gas is poised to begin construction on a $350 million pipeline project that aims to serve 15,000 homes and businesses from Gardiner to Madison within five years. Summit is anchoring the network with major manufacturers, including the Sappi Fine Paper mill in Skowhegan. Next year, Summit is scheduled to enter Falmouth, Cumberland and Yarmouth. The company hopes to reach 86 percent of potential customers in those towns within five years.

Summit’s business plan, if successful, is in itself a historic undertaking. Not since modern gas lines were expanded in southern Maine in the mid-20th century has such an extensive local distribution network been put in the ground.

• Meanwhile, Summit’s prime competitor, Maine Natural Gas, currently is bringing pipe into Augusta, with the goal of reaching 70 percent of the homes and businesses.

• Where pipelines don’t run, industrial users are so desperate for cheaper energy that they are having compressed natural gas delivered by tanker trucks that shuttle hundreds of miles a day between Boston Harbor and Maine destinations. Oil companies also have begun delivering CNG. New Brunswick-based Irving Oil earlier this month began trucking CNG across the border from its terminal in the province to the McCain Foods plant in Easton. Portland’s Dead River Co. has teamed with XPress Natural Gas to serve midsized commercial businesses across the state.

• As demand increases, pipeline developers are responding. Two existing, interstate pipelines are making plans to expand their capacity in New England.

But these expansions won’t be enough to satisfy Maine’s growing need. That has led some lawmakers to feel that state government should be given the authority to issue bonds and extract fees from utility customers to purchase new gas capacity. The idea is to team up with other states and businesses, to commit to buy enough new gas that developers would be enticed to build a new interstate pipeline into New England. Maine uses only 6 percent of the gas coming into the region, so no one will build new capacity just for Maine.

This concept, now part of a bill that faces a pending vote in the Legislature, is being championed by Rep. Kenneth Fredette, House leader of the Republican Party. Republicans typically urge a free-market approach to energy policy. But Fredette has said that the cost of energy is such a burden on Maine, the state needs to take a more active role to encourage the switch to gas.

Yet in their desire to provide relief from high energy costs, some policymakers may not remember that natural gas prices reached record levels, briefly, in 2008. They may not be aware that the steep, downward trend in wholesale gas reversed direction this year, and prices are rising. That could leave Maine vulnerable to higher heating bills if gas prices spike again, for reasons we can’t foresee now.

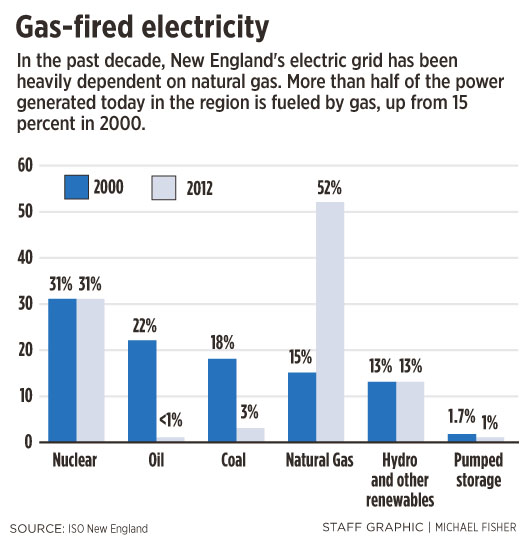

Natural gas now fuels more than half the electricity production in New England. The region got a taste of the consequences last winter, when a cold snap in January and a blizzard in February overwhelmed the gas supply, leading to shortages for power plants. That led to monthly, wholesale price peaks for gas, which carried over into electricity markets.

However, gas prices still are expected to stay low enough to maintain a long-term advantage over wind power, New England’s leading form of new, renewable power. As is, wind can’t compete with gas-fired electricity. No major projects would have been built without production subsidies and government policies that allow wind to be sold at above-market rates.

But when weighed against the impacts from Maine’s heavy reliance on oil, policymakers have for 30 years felt the trade-off was worthwhile, and have sought to diversify energy sources, as a hedge. Politicians from both major parties have passed laws that promote homegrown, renewable power, in part for the local economic benefits it can provide in the form of jobs and investment.

Those policies now are under fire from Gov. Paul LePage. He wants to turn away from ambitious goals to grow wind power as an industry, set in motion during the administration of former Gov. John Baldacci. LePage wants to reverse that policy and, in his words, “fast-track gas.”

‘A WICKED PRICE TO PAY’

These competing approaches to Maine’s energy future are rooted in two distinct points of view.

To Rich Silkman, the dominance of natural gas in Maine is inevitable and overdue. It’s worthy of a similar level of government support that first brought electricity and telephone service to rural America in the early 20th century, he said.

“I’ve never understood the argument for diversity,” said Silkman, a partner at Competitive Energy Services in Portland. “Over the past 30 years, diversity has made Maine’s electric rates more expensive. When you look at diversity, you really have to ask what the cost is.”

Silkman’s company started the natural gas project in the Kennebec Valley that’s now being sold to Summit. It also represents hundreds of businesses that want to convert to gas. Silkman rejects the argument that becoming dependent on natural gas puts Maine at risk for rising prices from unseen events. If and when gas costs rise to objectionable levels, Maine will shift to another fuel, just as it’s doing now with oil. That’s a better strategy than incurring above-average costs for decades, in anticipation of the worst case.

“It’s a wicked price to pay for insurance,” he said.

The shift to gas also threatens a local business sector that has seen its fortunes rise again with the price of oil — wood heat. Maine’s status as the country’s most heavily forested state has helped support an expanding supply chain that includes loggers, pellet mills and sellers of wood stoves and boilers. A homegrown fuel that’s cheaper than oil and carbon-neutral: It has added up to a compelling sales pitch that appeals to Maine’s sense of independence.

“In the short term, the rush to natural gas is going to make it challenging for those of us in the wood heat and pellet business,” said Phil Coupe, co-founder of ReVision Energy in Portland. “But gas is not a panacea. At the end of the day, it’s still a finite, nonrenewable fossil fuel.”

The company’s subsidiary, ReVision Heat, is promoting a European-made wood pellet boiler that installs for between $9,000 and $13,000, depending on the degree of automation. That’s more than a new gas boiler, but heating with wood keeps energy dollars in the state, supports local jobs and cuts the carbon dioxide emissions associated with climate change by 90 percent, Coupe said.

For these and other reasons, gas shouldn’t be considered “a silver bullet,” in the view of Beth Nagusky, Maine office director of Environment Northeast. It may be a cleaner-burning fuel, she said, but gas has impacts that are being largely downplayed by its supporters, including hydraulic fracturing that can pollute ground water, and methane emissions that speed up climate change.

“There’s a concern about becoming overly dependent on another fossil fuel, when we really should be getting off fossil fuels,” Nagusky said. “Being overly dependent on natural gas is not the answer.”

Natural gas should be viewed as part of a comprehensive energy strategy, she said. It shouldn’t be promoted over cost-effective energy efficiency measures, which Nagusky said should always have the highest priority. And gas should be compared to other heating options that may make better financial sense for some homes, she said, such as high-performance electric heat pumps.

But with the Northeast’s newfound abundance of natural gas expected to keep prices below oil for many years, the case for gas-fired power plants is just too compelling, according to Tom Welch, chairman of the Maine Public Utilities Commission. There just aren’t many other practical choices, Welch said. No new nuclear plants are being built in the region. Canadian hydro-power, while abundant, is priced for export into New England at market prices that track natural gas.

“So it’s not so much whether natural gas is a good idea, it’s just a fact,” he said. “The question is, what can Maine start doing now, to ensure it gets natural gas that’s closest to the wellhead price?”

WHO WILL PAY FOR PIPELINES?

Until the 1990s, Maine literally was at the end of a natural gas pipeline system that originated in the Gulf Coast. Then two interstate lines were built through Maine to bring new Canadian gas supplies into New England, from Nova Scotia and Alberta. These lines — the Maritimes & Northeast Pipeline, and the Portland Natural Gas Transmission System — led to the construction of gas-fired power plants in Maine, and helped bring gas to homes and businesses in communities that include Bangor, Windham and Brunswick. The line from Nova Scotia also made it attractive to build a terminal to import liquefied natural gas from overseas into New Brunswick and through Maine.

But in the past five years, the market changed in unpredictable ways. The gas deposits off Nova Scotia fell short of expectations. Another deposit off Newfoundland has taken longer than planned to bring online. New drilling technologies made it possible to extract a plentiful supply of gas from deposits in Pennsylvania and New York, essentially on New England’s doorstep. Those deposits, in the Marcellus and Utica fields, are so large that they have helped trigger a gas glut that collapsed prices and, as a side note, killed the economics of importing LNG.

This bounty of gas should be good for Maine and New England, but it’s more complicated. It gets back to the lack of pipeline capacity leading from Pennsylvania and New York into New England. This congestion means that on the coldest winter days, when gas is in high demand for both heating and power generation, there’s not enough to go around.

The simple solution is to build more pipeline capacity, but who will pay for it?

The existing pipelines came into being because revenue could be raised through the rates charged by local gas utilities. Today, the fastest-growing demand is coming from power plants. But in New England’s deregulated energy market, utilities don’t own power plants, so ratepayers can’t help foot the bill. Also, power plants don’t want to sign long-term contracts for large volumes of gas they might not need, if, for example, the winter is warmer than normal and people use less electricity.

“The traditional mechanism for funding pipelines doesn’t exist anymore,” Silkman said.

Worse yet, the supply shortage is jacking up the price Mainers pay for electricity. Although overall wholesale electricity prices fell last year in line with gas costs, the region still paid much more for gas than other parts of the country. That difference is costing New England roughly $3.5 billion a year in added costs for heat, electricity and manufacturing, according to estimates from Silkman’s company. Maine’s burden is $200 million a year.

NEW ENGLAND PRICES HIGH

That’s why two proposed expansions of existing pipelines are welcomed in New England. One involves the Portland Natural Gas Transmission System, or PNGTS, which connects lines in western Canada with the Maritimes line in Westbrook. PNGTS currently is seeking bids for new volumes of gas, with the aim of nearly doubling the capacity of its line, from 168,000 dekatherm per day to 300,000 in three years. One dekatherm equals roughly seven gallons of heating oil, so 300,000 dekatherm is the equivalent of 2.2 million gallons a day.

PNGTS offers the possibility of moving gas from Pennsylvania and New York over a line that runs through New York state into Ontario, bypassing the congestion in southern New England. But the expansion is dependent on a similar bidding process under way on the TransCanada Pipeline.

“Pipelines don’t build on spec,” said Cynthia Armstrong, director of marketing and business development at PNGTS. “We have to respond to firm commitments from the market.”

Also pending is an upgrade to the Algonquin Gas Pipeline, which runs 1,120 miles through New Jersey to Beverly, Mass., where it meets the Maritimes line. The Algonquin Incremental Market project will expand capacity up to 542,000 deckatherm/day in 2016, to serve local gas companies and power plants in New England.

Algonquin is owned by Spectra Energy Transmission, which is the lead owner of the Maritimes line. It is possible that the Maritimes line, which now pumps gas south through Maine, could be reversed to send plentiful Marcellus and Utica gas north for customers in Maine and eastern Canada.

“That’s something we’d have to look at,” said Marylee Hanley, a Spectra Energy spokeswoman. “At this point, we don’t have a request to do that, although the line is capable of doing that.”

Underlying these decisions is the cost of delivering gas. Although overall natural gas prices fell last winter by double digits, wholesale delivery prices in New England were the highest in the country. At the same time, the Northeast saw an expansion of pipeline capacity that ranked as the second highest since 1997, but none of it happened in New England.

The price difference between New England and other areas of the country will get worse before it gets better, according to Richard Levitan, president of Levitan & Associates in Boston, a wholesale power consultant. A new pipeline being completed into New York City this year by a Spectra Energy division, Texas Eastern, will provide heat for 2 million homes and save residents an estimated $700 million a year.

“It’s going to be very frustrating for the region to see declining (prices) in New York and New Jersey, and increases in New England,” Levitan said.

HOMES VS. BUSINESSES

But again, the price difference between natural gas in New England and oil is expected to remain wide enough for years to come to encourage conversions, at least for businesses. Big users, such as paper mills and factories, will reap the quickest savings, and are more likely to have capital to invest.

That highlights another open question about Maine’s rush to gas. How many of the seven in 10 Maine homeowners who now heat with oil will be able to take advantage of natural gas, and when?

Pipelines will never reach everywhere in rural Maine. And converting a typical central heating system from oil to gas can cost $6,000 or so. Proposals in the Legislature, and incentives offered by local gas utilities, will only pay for part of the total cost. And there’s debate over how much government should subsidize the conversion, and where the money should come from.

The outcome of this debate is important to Summit Natural Gas, with its ambitious penetration plans to quickly reach thousands of homes and small businesses. The company’s business model hinges on an energy fund managed by J.P. Morgan that has allowed Summit to raise $110 million for the first phase of construction. Connections to three paper mills will provide a shot of revenue for financing the project, which requires a 50-50 split of borrowing and equity.

Michael Minkos, Summit’s president, said this formula is unusual in the industry, because it has a higher level of risk. But the price margin between natural gas and oil, and the ability of a homeowner to save $1,000 or more a year, is driving this business model. Five years from now, it will be clearer whether Mainers were willing and able to hook up to gas, as experts were predicting in 2013.

“The most difficult challenge for this area remains the investment required,” Minkos said.

Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or at:

tturkel@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.