A restaurant owner’s responsibilities are spelled out in the state food code, and inspectors are trained for consistent enforcement.

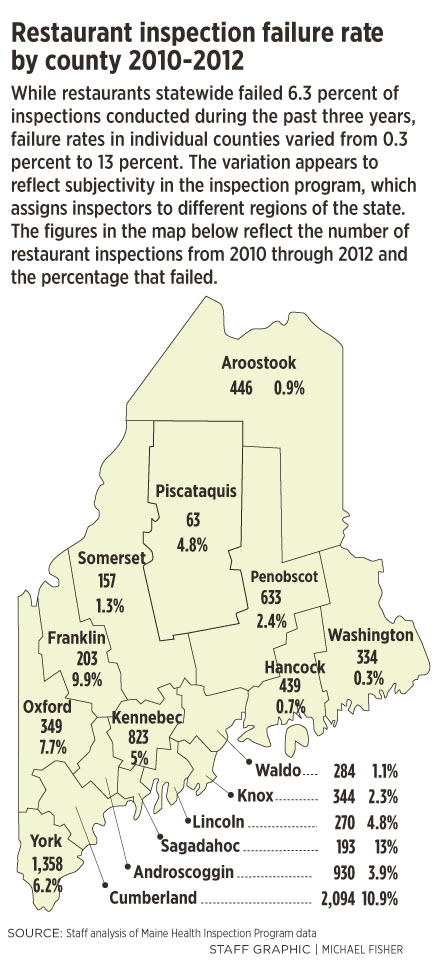

However, a Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram analysis of inspection results revealed a significant variance of failure rates from one county to another.

For example, only one out of 334 inspections in Washington County between 2010 and 2012 failed. That’s a failure rate of 0.3 percent.

But in Sagadohoc County, 25 out of 193 inspections failed. That’s a 13 percent failure rate — the highest in the state.

Cumberland County, meanwhile, is not far behind with a failure rate of nearly 11 percent — 228 failed inspections out of 2,094.

Lisa Roy, the state’s Health Inspection Program manager, said she had not conducted a county-by-county analysis of inspection results, so she couldn’t offer an opinion about why there was so much variance in failure rates.

Dick Grotton, president and chief executive officer of the Maine Restaurant Association, said the code is applied evenly throughout the state, even though some requirements, such as having a “conveniently located” hand-washing sink, can be subjective.

Grotton said the variance in failure rates could be attributed to the fact that some inspectors are more willing to work with an owner to correct violations without having to fail them on their inspection.

“I very much appreciate an inspector who uses common sense in interpreting the code,” he said.

The department conducts quarterly staff meetings and recertifies inspectors every three years — a process known as restandardization — to keep the state inspections consistent.

Scott Davis has been a state health inspector for the past 25 years. His territory is York County, and he is one of two people responsible for training inspectors to ensure consistency throughout the state.

Consistency is especially important to owners of franchise restaurants who must answer to corporate leaders regarding their inspection results. If one inspector cites a fast-food restaurant worker in York County for not wearing a hair net, but an Aroostook County inspector does not, businesses begin asking questions, Davis said.

One way to ensure consistency is to enforce the rules as they are spelled out in the code. However, Davis said it is more important to maintain a good relationship with restaurant owners.

“We’re not here to bust people’s chops,” Davis said. “We’re here to help them.”

On a recent inspection of the Stage Neck Inn, a seaside resort in York Harbor, Davis put that philosophy into practice.

Davis began by checking a walk-in cooler to make sure raw meats were stored in such a way as to prevent cross-contamination. He then tested the temperature of a variety of items in the cooler with a thermometer that he sterilized between tests. Davis did the same to a hot vat of chowder, before checking the dish-cleaning and bar areas.

Throughout the inspection, Davis used his flashlight to illuminate crevices, but made only a few notes on his clipboard. He marked down seven noncritical violations, including a dirty air vent, a refrigerator without a thermometer and single-service items, such as portion cups, stored on the floor.

But, when a pack of deli meat tested slightly above the 41-degree limit, Davis did not mark down the violation. Nor did he mark as a violation the storage of a sack of potatoes beneath a rack of packaged meat — a risk for cross-contamination.

Davis explained that the violations were not marked because other cold-hold temperatures were within allowable range and executive chef Lynn Pressey works to correct violations on-site. With regard to the deli meat, for example, Pressey called his handyman, who appeared minutes later to adjust the temperature in the cooler.

Also, the cooks were wearing thermometers, showing that they regularly test food temperatures, Davis said.

That approach puts chefs like Pressey at ease.

“In the beginning, I used to panic,” Pressey said of health inspections. “But I have known this gentleman for a long time. He knows we’re trying to do the right thing.”

Grotton conceded that inspections are “a little bit in the eye of the beholder.”

Perhaps nowhere is that more acute than in the Portland area.

When Michele Sturgeon worked in South Portland as an inspector, the rate of restaurants that failed was 25.4 percent in 2010 and 31.5 percent in 2011.

She left the job in 2011, and the rate dropped significantly. Only three restaurants out of 185 restaurants inspected in 2012 failed — a rate of 1.6 percent.

Sturgeon became Portland’s full-time health inspector in August of 2011 and failed 19 out of 23 restaurants that year — a rate of 82.6 percent. In 2012, about 40 out of 88 restaurants failed, a rate of 45.5 percent, and nine were closed because they were deemed imminent health hazards.

Before Sturgeon arrived, only 28 restaurants out of 556 inspected between 2008 and 2010 failed — a failure rate of 5 percent. None was closed or deemed an imminent health hazard as a result of the city’s inspections.

Sturgeon said she is not allowed to talk to the media without the city’s permission. Her boss, Douglas Gardner, director of the city’s Public Health and Human Services Department, said Sturgeon was “not available at this time.” City officials did not respond to requests for more information about why Sturgeon was not available.

“In terms of consistency, that is certainly a priority for us and the state, which is why every inspector must be recertified every three years,” Gardner said in an email.

Sturgeon went on medical leave in December. City Hall spokeswoman Nicole Clegg would not comment on her current employment status.

Roy said the department emphasizes working with restaurant owners and not marking down every violation that is witnessed by an inspector, unless an owner is unwilling to cooperate

“We want to work through education, first and foremost,” Roy said. “We don’t want to come down hard. We do want to work with people. You’re going to get better compliance with your licensee.”

Randy Billings can be contacted at 791-6346 or at:

rbillings@mainetoday.com

Twitter: @randybillings

Send questions/comments to the editors.