PORTLAND — Sarah Thompson and her husband, John, put two daughters through Portland elementary schools.

One went to Fred P. Hall. The other went to Longfellow.

As far as Sarah Thompson is concerned, neither child got a better education than the other.

That’s why she was surprised and frustrated when state officials issued grades for Maine’s public schools on May 1, including an A for Longfellow and an F for Hall.

Those vastly different grades, for two schools less than two miles apart, highlight the simplicity and pitfalls of the state’s new letter-grade system for public schools.

“I don’t understand that. They are both great schools,” said Thompson, a member of Portland’s school board. “The teachers are no less dedicated and the parents are no less involved at one or the other.”

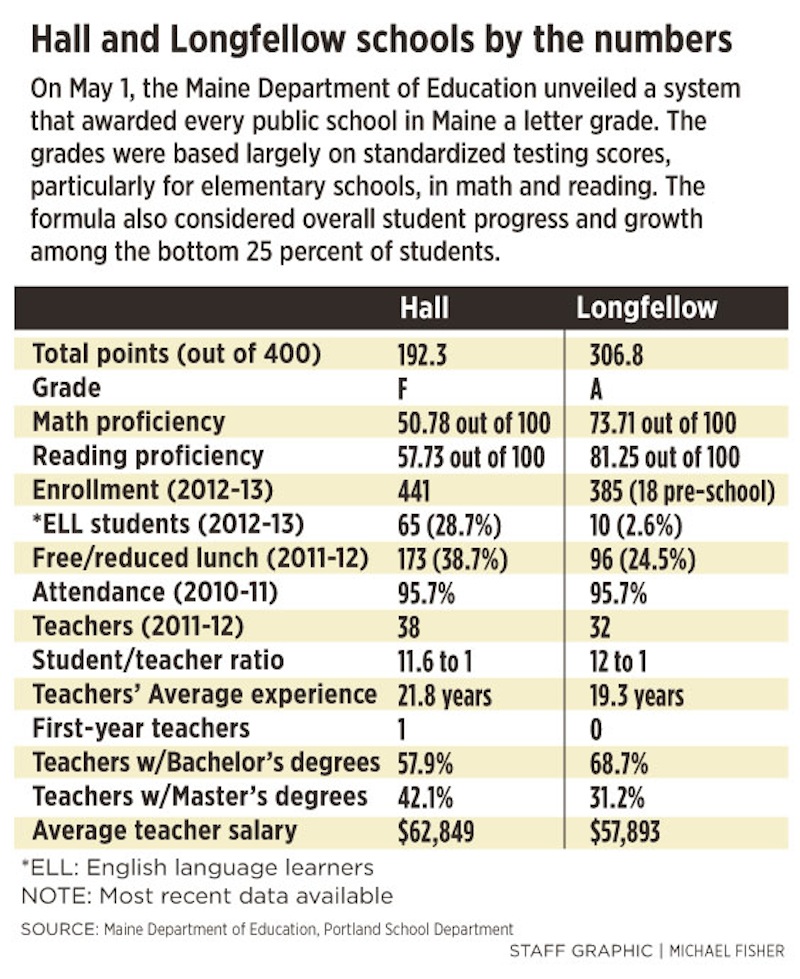

The schools’ grades were based in part on one day of standardized testing. By many other measures, Hall and Longfellow look almost identical: The buildings are about the same age, the student-teacher ratios are virtually the same, the average teacher age is comparable, and the average experience per teacher is close.

The average teacher’s annual salary at Hall, $62,849, is actually about $5,000 more than the average at Longfellow, and more of Hall’s teachers have master’s degrees. On paper, teachers at Hall are slightly more qualified.

There are two notable differences between the schools: At Hall, twice as many students qualify for the federal free and reduced-price lunch program, and more than six times as many are classified as English language learners, meaning English is not their first language.

No one should blame low-income students or English language learners for the school’s score, Thompson said, but to overlook the challenges that some of the students face would be ludicrous. Blaming teachers and schools is even more alarming, she said.

The state’s grades shouldn’t be a problem, she said, but “perception is reality for a lot of people. They are going to believe these grades if they don’t hear otherwise.”

School board member Justin Costa said he thinks the letter grades are punitive and counter-productive. “I understand that there is a whole group of people who want to see education become more data-driven and accountable, but this is not a valid model,” he said. “And instead of bringing together people to improve education, (the state) is putting educators and schools and parents on the defensive and creating animosity.”

Education Commissioner Stephen Bowen said the reaction to the grades has been mixed, but he’s glad that people in communities statewide are talking about education.

“We don’t want the grades to just sit there for a year,” he said. “We want to see what we can learn from them.”

A CLOSER LOOK

In the new grading system, elementary schools were compared through the latest New England Comprehensive Assessment Program scores for reading and math. The system also considered growth over the previous year at each school in each subject.

With that formula, Longfellow received 306.8 points and Hall got 192.3 points, which translated to an A and an F, respectively.

Portland school officials denied a request by the Portland Press Herald to spend time inside the two schools to look at possible differences in teaching and learning. Superintendent Emmanuel Caulk said he did not want to pit schools against each other.

When the grades were announced, however, Caulk released a statement that urged parents and teachers not to put too much stock in them.

“In the Portland Public Schools, we do not assess a student’s year-long performance based on a single test, as we know it is not an accurate reflection of learning,” he said. “Similarly, we do not judge the quality of our schools on a single measure and instead review a range of assessment and data analysis to develop plans for success at all schools.”

Michelle Renee, with the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University, said she’s not familiar with Maine’s letter-grade system, but she has seen other states adopt similar models.

“The idea is intrinsically good, I think, but where it goes empirically backwards is when you rely on standardized tests,” she said. “Many states, in fact, are moving away from standardized tests altogether.”

Longellow Principal Dawn Carrigan and Hall Principal Cynthia Remick said they are proud of their teachers and schools, but are concerned about the impact of the state’s comparison of schools so close to one another.

Carrigan said her staff in no way celebrated its A. It’s hard to feel good about the grade, she said, when other schools were at the opposite end of the scale.

Remick said she and her staff have been heartened by strong public support since the grades were announced, but she, too, is worried about perception becoming reality.

The worst part, Remick said, has been students talking about their school’s failing grade. She said they felt responsible.

One factor that the state did not take into account was an electrical fire at Hall in September that forced the school to close for a week. Students took a standardized test — the test that would form the basis of their failing grade — the next week.

State officials have acknowledged that the grading system is simplistic, but said that is deliberate. Bowen said the grades were designed to grab attention.

In addition to releasing the letter grades, the Maine Department of Education created a “data warehouse” on its website with the hope that visitors will delve into the reasons that schools got the grades they did.

The problem with that, Costa said, is that most parents probably won’t take the time to examine that level of detail.

David Silvernail, director of the Center for Educational Policy, Applied Research and Evaluation at the University of Southern Maine, said the grading system would be much fairer if it considered socioeconomic factors.

Bowen said his staff considered doing that, but worried about creating two sets of standards.

“We don’t want to tell schools that have a high percentage of low-income students that they should be adjusted because they can’t do as well as other schools,” he said.

Gov. Paul LePage’s spokeswoman, Adrienne Bennett, said the governor does not believe that income barriers define destiny. She noted that nearly two dozen schools where more than 50 percent of the students get free or reduced-price lunch received A’s and B’s.

“Poverty does not equate to failure, and we hope these grades and the data website will lead to healthy conversations about how these high-poverty schools are achieving great results,” Bennett said.

LONG-TERM EFFECTS?

Parents of Hall students have disputed the notion that the school is failing, but said they are concerned about what an F will mean in the long term.

Shannon Doughty, the mother of a fourth-grader and a first-grader at Hall, said she thinks the state is effectively penalizing schools for their diversity. “I’ve been extremely happy with the school,” she said.

Sean Kelsey, who also has two children at Hall, said he worries about the grade’s effect on teachers. “I can’t believe it won’t affect the morale of teachers, who are already dealing with budget cuts,” he said.

Parents of Longellow students were glad that their school did well, but were sympathetic to the parents and teachers at Hall and other Portland schools, such as East End Community School, that didn’t fare as well. East End also got an F.

Marnie Morrione, who has a fifth-grader at Longfellow and a sixth-grader at Lincoln Middle School who attended Longfellow, said the only differences she sees are demographic.

“Longfellow is not a very diverse school,” she said.

Morrione, who also is on the school board, said it’s clear to her that the letter grades are designed to pit schools against one another to generate more support for school choice and charter schools, something the governor has pushed for since he took office in 2011.

“There are no recommendations for improvements and no funding,” she said. “Is the message to just do better on one test? That’s not what we should be pushing.”

Bowen, however, said the Education Department already is contacting schools that received D’s and F’s to learn how the state can support them.

Renee, with the Anneberg Institute for School Reform, said that if the state is trying to motivate schools, this isn’t the way to do it.

“You can’t treat education like you’re producing widgets,” she said.

Costa, the school board member, said it’s bad enough for Portland students to worry about being inferior to those in more-affluent Falmouth or Cape Elizabeth. They really shouldn’t have to worry about that within their own school district, he said.

But Portland isn’t alone. In South Portland, three elementary schools within a mile or so of one another — Dyer, Brown and Kaler — ran the gamut. Dyer received an A, Brown got a C and Kaler got an F.

One potential side effect of the system is that parents with students in “failing” schools might consider out-of-district placement.

Portland has 10 elementary schools. In general, students are placed in schools based on where they live. But if a parent petitions the school department, a child can be moved.

The problem for the school district is making sure that enrollment is generally equal from school to school.

Sarah Thompson said she doesn’t think the grades will prompt more parents to consider out-of-district placement for their children, but she acknowledged that it’s a concern.

David R. Garcia, a professor at Arizona State University who helped create a school accountability system in his state, said even though they aren’t necessarily effective at improving schools, grading systems don’t cause as much turmoil as people fear.

For the moment, Portland officials are walking a fine line between ignoring the letter grades and working hard to fight public perception. “We need to focus on the things we know are working,” said Morrione.

Costa said he hopes that parents will take it upon themselves to hear from schools and teachers directly, rather than relying on politicians in Augusta to assess their schools. “Every school has a success plan, a plan for improvement,” he said. “And that’s true of schools that are doing well. Even they can improve.”

Eric Russell can be contacted at 791-6344 or at:

erussell@pressherald.com

Twitter: @PPHEricRussell

Send questions/comments to the editors.